The ongoing public discourse in Israel encompasses much deeper and wider sentiments than just the discussion about reforms in the judicial system. Although changes in the Israeli Judicial Selection Committee or the override clause are significant, they do not address the crux of the matter.

The real issue at hand is the battle for the identity and nature of Israel and whether its political system should be representative of the majority of the public, as is expected in a democratic republic. Alternatively, it should continue to cater to closed and unelected elitist groups who have lost touch with the general public.

This raises a broader question: Should Israel be a Jewish state or a multinational state?

Should Israel be a Jewish state?

The struggle for the public sphere and the identity of Israel dates back to its very inception and even before. This period marked the first phase in the establishment of Israel, during which its national and public identity was being formed and defined. On one hand, there was a secular, socialist faction comprised mostly of Jews from Eastern and Central European countries. They aimed to create an image of the new Israeli.

On the other hand, there was a religious faction that had not fully assimilated during their exile and kept the remnants of their religious tradition. However, it is crucial to note that members of the Zionist Left during the establishment of the state were considered almost as learned as rabbis, compared to the current Left’s anti-religiousness and lack of knowledge about the religious tradition. While the religious camp sought to uphold a Jewish state in Israel, the socialist Left sought to maintain a state for the Jews.

THE DISAGREEMENT between the two factions is what has prevented Israel from adopting a constitution thus far. However, both camps share a fundamental principle – Zionism – and a central objective – to establish a Jewish homeland. This essential agreement allows for the possibility of setting aside their differences and collaborating toward the creation of Israel.

Wars waged against young Israel by Arab nations in its early years and beyond have delayed the necessary discussion regarding the public sphere and character of the country. The second phase in the country’s development then ensued – the 1977 “political revolution,” which marked the ascension of the right-wing to power following almost 30 years of unchallenged political control by the socialist Left in Israel.

This transformative and historic shift was meant to sway the nature of the country and public sphere towards the Right, which has predominantly held sway in Israeli politics since then, especially following the collapse of the Oslo Accords and the aspiration of establishing a Palestinian state.

Even then, both the right and the left succeeded in stalling the public-political decision. The Right’s unexpected victory in 1977 caused immense fear and alarm within the left-wing faction, which had unchallenged political influence in the government ministries, the workers’ union (Histadrut), academia, the media, the security forces and nearly every organization or institution controlled by the Left for decades.

It is worth noting that in those days, as is the case today, the media circulated messages infused with hysteria, intimidation and incitement against the right-wing’s “fascism,” and a sense of apprehension regarding the state’s continued existence.

In order to appease and calm the concerns of the Left camp, the Right at that time rushed to make an unwritten alliance with the Left. Namely, the Right would indeed control the government and the Knesset but the Left would continue to benefit from the restraint of the Right and its majority through the appointment of officials, legal advisers and justices in the High Court sympathetic to the ideology of the old guard.

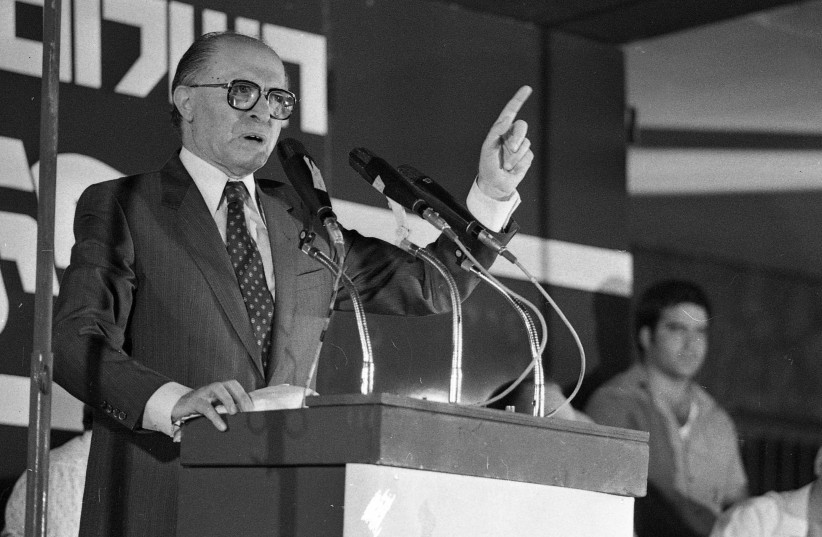

In other words, as the late prime minister Menachem Begin coined: “There are judges in Jerusalem.” Indeed, it was Begin who miraculously raised the level of the judicial system, in a move that the right-wing camp laments to this day.

The left-wing camp has managed to maintain its political power through indirect means, including the legal system, bureaucracy, media and academia, despite their limited success in democratic elections. The apex of this power came in 1992, with the “judicial coup” led by former Supreme Court judge Aharon Barak.

DESPITE BEING repeatedly elected by the majority of voters, the Right has been thwarted in its attempts to reflect the will of the public in areas such as the economy, security, society and religion-state relations. The Left, through its de facto political power in the corridors of power, has prevented any possibility of shaping the public sphere according to the will of the conservative camp, which comprises the majority of voters.

The current government’s aim to promote legal reform is intended to finally reflect the will of the sovereign people, who are predominantly conservative. This conservative public, comprising ultra-Orthodox, religious, traditional and secular individuals with an affinity for Jewish tradition, has consistently turned out to vote and seeks to shape public life in accordance with its values.

This stands in contrast to the opposing camp, which strives for an extremely secular, liberal, multinational state that promotes progressive values. The legal reform is intended to ensure that the public sphere in Israel aligns with the existing characteristics of the majority of the population.

For the first time since the establishment of the state, the left-wing camp is now acknowledging the impending collapse of its anti-democratic political stronghold, which has allowed it to indirectly control the public sphere and discourse and hindered the shaping of Israel based on the results of democratic elections.

This legal reform marks the first time that the conservative majority will be able to shape public life in accordance with their values, in contrast to the left-wing’s efforts to promote progressive, secular, liberal and multinational values.

The opposition’s extreme, hysterical and exaggerated reactions to the legal reform are driven by a deeper motive than just the reform itself. It is a battle for the identity of Israel.

This battle has been going on for decades and the legal reform is a key component of the Right’s efforts to finally assert the will of the people. It is time for the right to assert itself with confidence and proclaim, “There is democracy in Jerusalem and a sovereign in Israel.” It is time to govern.

The writer is a researcher and Israeli publicist. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Studies.