Democracy’s most glaring weakness is its lack of an inherent moral code for ethical evaluation. Aware of this deficiency, those who drafted Israel’s Declaration of Independence decided that the state’s values would be taken from the cultural dimension of Judaism (not the religious dimension) and that they would be the universal values embodied in the “morality of the Prophets,” adherence to which is open to all citizens, even those who are not religiously observant or not Jewish.

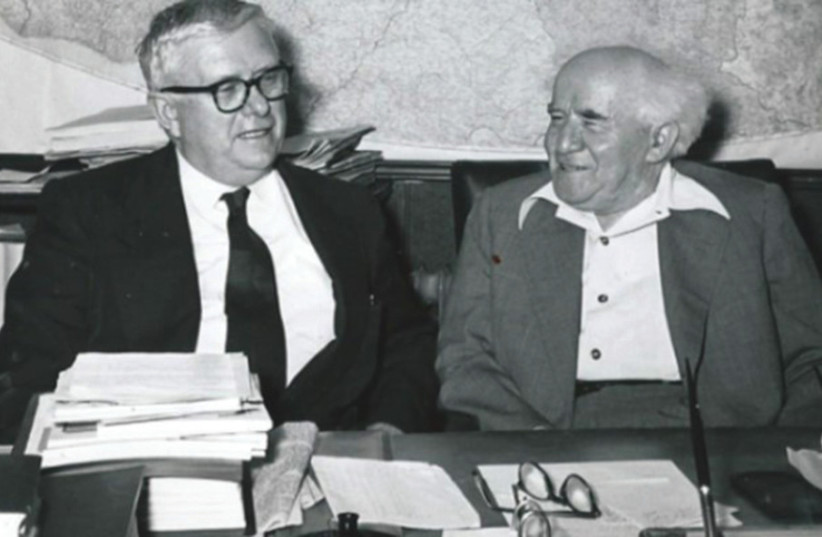

Former prime minister David Ben-Gurion wrote in his diary: “I am in favor of Jewish democracy – the Western kind isn’t enough... We have a unique Jewish [cultural-moral] substance that ought to be the inheritance of the world.”

In law, morality is necessary for mishpat tzedek (justice) to be done and if justice is done and seen, peace will result.

Adjudication based on the values set forth in the Declaration of Independence and in two Basic Laws that accord it constitutional status (Basic Law: the Judiciary, 1980; Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty, 1992) entails strong familiarity with Jewish law.

Go and learn

That is Hillel the Elder’s “the rest is the explanation – go and learn,” which is necessary not only in a case of non-liquet (lacuna in the law) but in all rulings; without Jewish law, the state’s values, interpreted in the spirit of the time and its challenges, are like “a stone that cannot be overturned,” i.e., a useless object or dead weight, and the Basic Laws are effectively violated.

In 1980, justice Aharon Barak decided that Jewish law would be merely a source of inspiration to judges, thereby relegating it to a lower standing than that accorded to the legal sources of other democracies, some of whose foundational values directly clash with the state’s legally-enshrined values.

In the wake of this decision and contrary to the basic democratic principle of equality before the law, two different types of judge and adjudication emerged in Israel: “conservative” judges who regard themselves as bound by the legally-enshrined values of the state and are cognizant of Jewish law and “liberal” judges who also adjudicate on the basis of values contrary to those enshrined in law.

What is reasonableness?

Beyond this, another antidemocratic distortion arose: that of “reasonableness” – a legal concept that has become illegitimate as it embodies the judge’s ethical discretion in accordance with unknown values, some of them contrary to legally-enshrined values.

Like a transfusion of different blood types, the cocktail of values that was infused into the state’s veins generated a major catastrophe: a deep rift between the judiciary and the (Right-leaning or Left-leaning) governments obligated by the Declaration of Independence and its values. Governance was compromised and anarchy took hold; Israel’s national cohesion, a product of shared commitment to the Declaration of Independence and its values, disintegrated and Israel lost the identity with which its founders had imbued it.

IN 2019, Barak disavowed his 1980 decision: “[In adjudication] one must take values into account... It is not the values of the judge but rather the values of society... Israel’s values as a Jewish and democratic state – who invented them? Not I. It was the Knesset, in Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty and the intellectual father of this concept is Rav Yitzhak Levy, who was a member of the Constitution Committee... The values that I invoke are not values from outside the law... The Declaration of Independence is within the law because Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty says it is based on the Declaration of Independence.”

Barak also recently admitted that he was unfamiliar with Jewish law (whose sidelining severed Israel from both its Jewish and its democratic character).

In light of the above, the judicial system should use its independence (an independence that must be safeguarded) to restore Jewish law to its rightful place, interpreted in the spirit of the times and its challenges, so that all of the country’s judges, regardless of their ethnicity, their temperament or their political outlook, will adjudicate in accordance with it and justify this in their rulings. The annulment of Barak’s decision will halt the distortion of the law, obviate the need for the reform and end this distressing crisis.

It may be that, as in Samson’s riddle, “sweetness” will come forth from the strong. The present “coalition of the misguided” – the judicial system that spearheaded the cultural revolution, the “reform” advocates who have not recognized Israel’s estrangement from its Judaism and the protest movement that has failed to perceive that for 40 years Israel has been a democracy in name only – must join hands and become a restorative coalition.

A document will shortly be drafted that will specify and elucidate the values of the state, in accordance with the present period and its challenges;

Israel’s education system will mobilize to inculcate the document’s values and the Knesset, the government and other bodies will incorporate values-based adjudication into their activity;

Conflicts will be resolved through compromise on the basis of ethical democratic discourse, rather than through an everything-is-justiciable-inspired mad rush to adjudication and legislation.

It will be recognized in Israel and around the world that Israel, as intended by its founders and in accordance with its Basic Laws, is neither a halachic state nor an ordinary Western state but rather a unique democracy whose cultural values make it a Jewish democracy.

The writer is a lecturer in military and political strategic thinking at Bar-Ilan University.