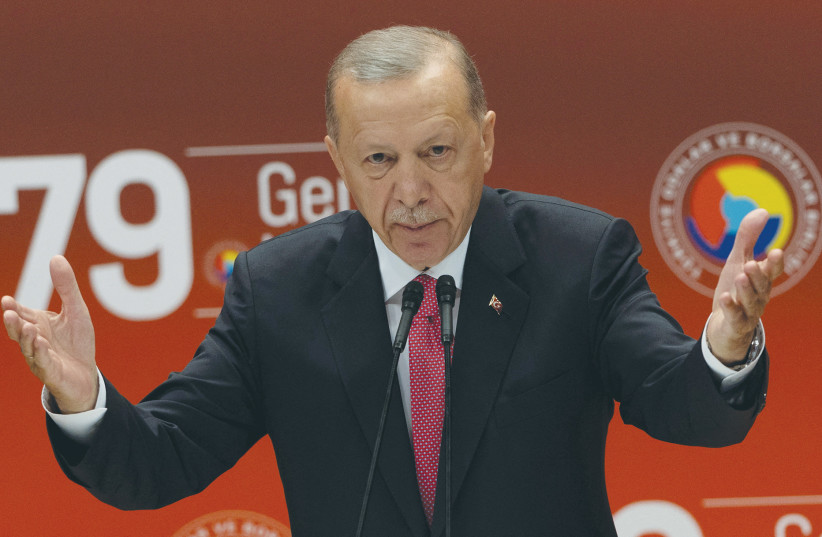

I was on holiday in Turkey (now officially named Türkiye) during the first round of the presidential elections when President Recep Tayyip Erdogan fell just 0.48% short of winning reelection. Two weeks later, on the May 28 runoff ballot, the Ankara strongman achieved victory with 52.18% of the vote.

Questions have been raised about the fairness of Turkey’s elections, with critics pointing to how Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) dominates the airwaves. I saw this firsthand, watching the results come in at the home of a Turkish host who, to get the full picture, zapped between different news outlets, from pro-government to pro-opposition channels – there being far more of the former than the latter.

If the Israeli public could determine the outcome of Turkey’s election, there would presumably have been an opposition victory, it being widely believed that Erdogan’s brand of political Islam encompasses ideological hostility toward the Jewish state.

Ankara-Jerusalem ties were much more positive when I first entered Israel’s Foreign Ministry in 1990. That period was considered the “golden age” in bilateral cooperation, which was showcased as an example of how a member of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) could maintain excellent relations with Israel.

From the hundreds of thousands of Israeli tourists visiting Turkey annually, to the Israel Air Force and Turkish Armed Force’s joint air-training exercises, the two American allies enjoyed a robust and multifaceted partnership.

DESPITE TURKEY’S vote against the November 1947 UN partition plan for the establishment of a Jewish state, just two years later it became the first Muslim-majority country to formally recognize Israel.

David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s founding prime minister, attached special importance to ties with Turkey. He advocated what was known as the “periphery doctrine,” which sought to compensate for Arab hostility by cultivating strong relationships with pro-Western nations on the edge of the Middle East – Imperial Ethiopia, Pahlavi Iran and Republican Turkey.

Turkey's ties with Israel: A relationship of ups and downs

Over the decades, Ankara’s ties with Jerusalem always had their ups and downs: the Turks, though not necessarily having an automatic affinity with the Arabs, nonetheless displayed a measure of Muslim solidarity, and consequently, the periodic escalations in the Arab-Israel conflict tended to negatively impact Turkey’s relations with Israel.

Under Erdogan’s rule, it was more down than up, although it started off well enough in the years immediately following the AKP’s November 2002 electoral breakthrough.

In May 2005, Erdogan visited Israel with a delegation of business leaders to bolster trade ties. He was also eager to strengthen defense cooperation and carve out a role for Ankara in Arab-Israel peacemaking. During that visit, he declared antisemitism a “crime against humanity.”

The following year, as Foreign Ministry spokesperson, I participated in a meeting between foreign ministers Tzipi Livni and Abdullah Gul. Emblematic of the strong relationship, Gul praised Israel’s sensitive handling of tensions around al-Aqsa Mosque.

At the time, it was said that the AKP’s brand of moderate Islamism was a cousin of European Christian Democracy and no obstacle to good relations with Israel.

It was not to be. In December 2008, amid Turkey’s attempt to mediate between Israel and Syria, Operation Cast Lead was launched against Hamas in Gaza. Erdogan fumed, believing that prime minister Ehud Olmert, whom he had just met, deliberately misled him about the upcoming IDF operation.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2009, Erdogan famously confronted president Shimon Peres, walking off their shared stage in protest.

The May 2010 Mavi Marmara incident, with its Turkish fatalities, further exacerbated the crisis. Erdogan denounced the Israeli Navy’s interception of the Gaza flotilla as “state terrorism.”

UNDER ERDOGAN’S leadership, Ankara’s traditional pro-Western orientation would be eclipsed by a new Middle Eastern identity. During the Arab Spring, he presented Turkey as the Islamic democratic model for the Arab world.

Touring North Africa in September 2011, Erdogan received rapturous welcomes. But being the standard bearer of Arab revolution was not conducive to maintaining good ties with Israel, and he was soon condemning Zionism as a “crime against humanity.”

In March 2013, president Barack Obama brokered a reconciliation deal: Benjamin Netanyahu expressing regret for any errors in the Mavi Marmara interception and agreeing to compensate the families of the dead Turks, and Erdogan dropping war crimes charges against the IDF personnel involved. But any détente was short-lived.

In October 2013, The Washington Post reported that Ankara helped Tehran uncover Mossad operatives in Iran. And Operation Protective Edge in Gaza in July-August 2014 saw Erdogan accuse Israel of attempting a “systematic genocide of Palestinians.”

Early 2016 saw a renewed effort to normalize ties, but any progress proved ephemeral, with Erdogan responding furiously to president Donald Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. Ankara declared a three-day period of national mourning and hosted an emergency Organization of Islamic Cooperation summit to denounce America and Israel.

Increasingly, those responsible for Israel’s domestic security became uneasy about Turkish activity on the Temple Mount and its support for local agitators.

Like Islamists elsewhere, Erdogan has espoused antisemitic prejudice, even implying that domestic opposition to his protracted rule was connected to the “seed of Israel” and the “interest-rate lobby.”

ERDOGAN’S PARTIALITY toward Hamas has been a special problem. Despite Ankara’s commitment to the contrary, Hamas cadres continued instigating terrorism from Turkish soil.

In May 2018, responding to the deaths of 60 Palestinians during Hamas-instigated riots on the Gaza perimeter fence, Ankara expelled Israel’s ambassador Eitan Na’eh. The Turks invited journalists to film the Israeli diplomat undergoing a security check as he exited the country.

An opportunity for better ties emerged with President Isaac Herzog’s March 2022 visit to Ankara. At the official welcoming ceremony, Erdogan declared that Israeli-Turkish relations are “of great value for our countries.”

That visit was followed by meetings between foreign ministers and the exchange of ambassadors – Israel’s Irit Lillian presenting her credentials to the Turkish president on December 27, 2022.

After Erdogan’s recent reelection, Herzog tweeted: “I am convinced we will continue to work together to strengthen and expand the good ties between Turkey and Israel.”

These words may be more than diplomatic niceties; the heterogenic Turkish opposition bloc unsuccessfully trying to unseat Erdogan contained both dissident Islamists as well as leftists, with neither grouping favoring rapprochement with Israel.

Paradoxically, those hoping for improved Israel-Turkey ties can welcome Erdogan’s electoral triumph. In the current Turkish political reality, perhaps he alone – despite all his anti-Israel and antisemitic baggage – has both the capacity and the motivation to deliver a healthier Ankara-Jerusalem relationship.

The writer, formerly an adviser to the prime minister, is chair of the Abba Eban Institute for Diplomacy at Reichman University. Connect with him on LinkedIn @Ambassador Mark Regev.