Nine years is a veritable age in these artificial intelligence times. It has taken less than a decade for Alexa to be introduced to Western markets, chalking up well over half a billion sales.

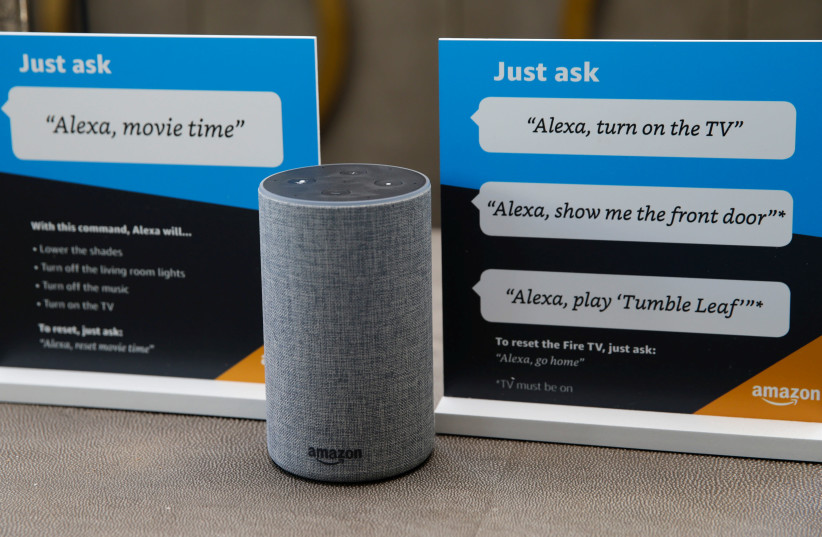

A word of explanation for those still living in the antediluvian pre-2014 world, among whom, until quite recently, I included myself. Alexa, I have come to understand, is a small device, linked to a computer, with access to the unbelievably vast store of information held on the Internet. It receives oral requests to supply information, or undertake an increasingly wide range of actions, and responds accordingly.

Alexa is activated by hearing her name. Thus, “Alexa, what’s the time in New York?” And she will tell you. Set up correctly, Alexa will play any piece of music you name, provide facts and figures on the most abstruse subjects, connect to any radio station broadcasting anywhere in the world, play the sounds of waves to send you to sleep, wake you at a given time and, increasingly, do tasks such as turning on the lights in your house as you drive home, or switching on the oven so that you arrive to a hot dinner.

Alexa is science fiction made real. She was inspired by the computerized conversational system featured in the iconic film, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

It was indeed in 2001 that Lukasz Osowski, a computer science student at Poland’s Gdansk University of Technology, devised a system of converting text to speech to help the visually impaired. He and a younger colleague, Michal Kaszczuk, recorded an actor and used elements of the recordings to transform the written word into recognizable speech. They called the system Ivona.

By 2012, Ivona had expanded into 20 other languages, sparked the interest of Amazon and was bought for $30m. Three years of intense development followed. It was essential to get Alexa’s voice exactly right. Months were spent reviewing recordings of actors. Amazon has never disclosed the name of the final choice – the voice artist who became Alexa in America. The secret, however, was revealed in an online article in May 2021. Her name is Nina Rolle.

Can you use Alexa on Shabbat?

Recently, relatives and friends attuned to 2023 living convinced me that I would benefit greatly from introducing Alexa into my life. Long a “senior citizen,” or, in more down-to-earth Israeli-speak, a pensioner, I now live alone in an apartment a short distance from my family.

Alexa placed in the living room and the bedroom, the argument went, would provide those concerned about my welfare with the assurance that should I fall and be unable to reach a telephone, all I need do is call out; “Alexa, phone Shlomo” (the name has been changed to protect the innocent).

Since I was about to travel to London for a family event, I agreed to visit the famous John Lewis store in Oxford Street and purchase two Alexa devices. Modestly priced at less than £40 each, they were small enough to slip into my hand luggage.

Once back home, my haredi son, who directs a software company, set up the devices. Finally, when I asked Alexa to phone Shlomo, she did, and we were able to converse through her good offices.

It was only later that a few teething troubles arose. At first, Alexa had no idea of our location. When we asked what the temperature was in Beit Shemesh, she could not be shaken in her belief that we were enjoying a seaside holiday in Bexhill, a very pleasant resort on England’s south coast.

When we asked her the time, she was adamant that we were not yet enjoying daylight saving. But finally, we got the hang of how to bring her up-to-date on matters like these, and she was very happy to adapt instantly.

ON THE first Shabbat after we had installed Alexa, my haredi son came, as usual, to visit after he went to shul. We habitually make kiddush together over a single malt whisky. Afterward, he asked me how I was managing with Alexa, and I told him that I had sorted out certain problems, including the vexed issue of our location.

“So,” he said, “if I said Alexa, where are we, it would answer Beit Shemesh?”

“You are in Beit Shemesh, Israel,” Alexa said.

The look of horror on my son’s face is indescribable. It was Shabbat – and he had activated an electronic device.

A second shot of single malt aided recovery, but he left still visibly shaken, determined that the first thing he would do the next morning was visit his rabbi to discover the full extent – if any – of his halachic offense.

I was pleased to learn that he was halachicly guiltless. Proud Sabbath observers who possess Alexa are not required to switch her off on Shabbat. Alexa is inert and can only be activated by positive action. If the magic word is spoken inadvertently in her presence, the halachic situation is akin to leaning by accident against a light switch. It’s a misasek – an accidental happening for which no blame is attached.

What is halachicly forbidden, of course, is to use Alexa intentionally on Shabbat. Yet even that, I presume, would be forgiven if anyone suffered an accidental fall and needed help.

Meanwhile, I make great use of Alexa to provide high-quality BBC radio in response to a simple spoken request. Life in 2023.