A Jewish state or a state of Jews? What are we? The answer is a bit complicated.

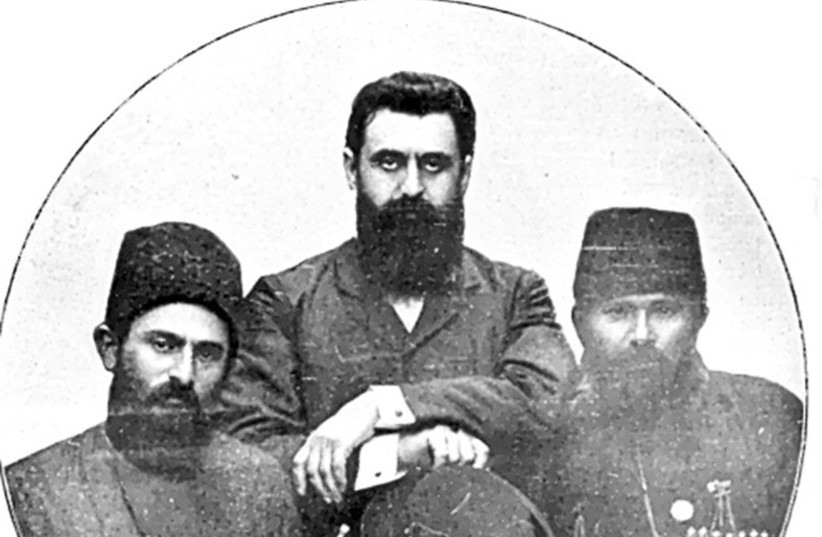

In the 19th century, nationalism played a major role in identity. For Jews, nationalism as a modern concept was germinated years before Theodor Herzl, by Moses Hess in his 1862 book Rome and Jerusalem; and it found allies in the Russian Hibat Zion (Hovevei Zion) movement of the 1880s.

Hibat Zion was the umbrella organization for an interesting mixture of traditional and modern Jews, and found its practical expression in the settlements of the first aliyah, or mass immigration, in 1882. Herzlian Zionism arose as a practical outcome of the need to address the growing antisemitism of the late 19th century.

The first Zionist conference in Basel in 1897 sought a common ground that would appeal to both secular and religious Jews, which was the need for a state to shelter Jews from antisemitism. This common purpose could explain the bizarre saga in which the British promised Herzl a Jewish state in Uganda (today’s Kenya), an idea discussed seriously at the Fifth International Congress of Zionists. This was an act of desperation in the face of the Kishinev pogrom of 1903.

The early 1900s brought halutzim (settlers) who were the carriers of new ideologies. As the new Zionists were predominantly from Russian backgrounds, they brought with them the socialist ideals of those countries in a Jewish context. Members of the first aliyah of 1882 may have believed in the importance of building settlements and agriculture, but the second aliyah made it a sacred ideology. Ideologues like Labor Zionist A. D. Gordon (who moved to Ottoman Palestine in 1904) saw a return to the land almost as a spiritual revival, with agriculture at its core.

The idea of communal life and building a new future for the Jewish people bore quasi-messianic elements. This second aliyah, being highly ideological, had a profound impact on the socialist-Zionist identity of the future state. The third and fourth aliyot were the result of economic difficulties and the closing of doors in Western countries to Jewish immigration. The fifth aliyah comprised Jews in flight from Nazi Germany.

From that point on, all major influxes of immigration to Israel were composed of Jewish refugees running for their lives.

The diverse streams of immigration to Israel

In the wake of the Holocaust, hundreds of thousands of survivors made their way to the future State of Israel, despite the British blockade. After the founding of the state, the number increased to half a million. The Holocaust was seen by the founders of the state, and especially by the first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, as the ultimate justification of the Jewish state as a shelter for Jews in flight.

It also rendered the issue clear that the heavy price needed to be paid to create a state was now justified. In 1948, when prime minister Ben-Gurion spoke of his intentions to declare a state on the day of the British departure, United States president Harry Truman warned him that if he were to declare a state, five Arab countries would declare war against it.

Ben-Gurion asked Yigal Alon, his intelligence minister in The Jewish Agency for Israel, what the chances were of the new state surviving such an attack. Alon answered, “Not more than 50-50,” to which Ben-Gurion replied with a question: “In the past 2,000 years, when did the Jewish people have such good odds to recover their own state?”

From this point forward, immigration to Israel was predominantly composed of Jewish refugees essentially banished from their birth lands, such as made up the major immigration of Jews from Arab countries from 1949 until 1955. By 1970, these Jews made up 650,000 new immigrants to Israel.

From 1956-60, approximately 50,000 people immigrated to Israel from Poland after being “encouraged” to do so by the Gomulka government. From 1969-1973, about 163,000 immigrated from what was then the Soviet Union. The 1980s brought a wave of aliyah from Ethiopia, and the 1990s saw another major wave of immigration of more than one million people from the former Soviet Union.

These waves of immigration of Jewish refugees eventually made up approximately 85% of the country – and perfectly fit the narrative of a shelter-state for the Jewish people.

In addition to seeing the state as a shelter against persecution, the early leadership of the state viewed it as a secular entity. This was not stated as an official declaration but was intrinsic to the leadership’s socialist background and philosophical outlook.

New immigrants were made to understand that religious life was not in harmony with the new life in Israel. From the beginning, however, the leadership understood that their vision of a secular Zionist state did not reflect the reality on the ground.

In the 1950s, Dov Yosef, in charge of food rations in Jerusalem during the years of shortages, took a survey to find out how many Jews in Jerusalem insisted on kosher meat. The result was over 80%. In the late 1950s and 1960s, the aliyah from Arab countries was comprised predominantly of observant Jews whose traditional practices persisted, despite attempts to place their children in secular schools.

By 1970, some 51% of the country was of Mizrahi origin (descendants of Jewish communities from the Middle East and North Africa). The Labor Party always included the Ashkenazi-led religious parties in their coalition, but it was clear that the country’s demography had changed.

Traditional Jews saw the state not just as a state of Jews in times of persecution but also as a Jewish state, as part of the biblical promise of the ingathering of the exiles. This was a different narrative.

THE SIX Day War was the watershed moment of collective Israeli identity. The lightning strike against the state’s bordering enemies and the liberation of Jerusalem, the Western Wall, and the Temple Mount created a shock wave effect and a renewed Jewish national identity. Secular poets such as Haim Gury wrote with emotion about the paratroopers at the Western Wall.

Naomi Shemer, a product of the Labor Kibbutz Movement, wrote her famous song “Jerusalem of Gold,” and Natan Alterman, the poet of the Labor Movement, was a founder of the movement for the greater Land of Israel.

It suddenly appeared to all, even for a moment, that the State of Israel was not only the main center for Jews but also for Judaism. It also had a ripple effect among Jews worldwide.

This was a moment that demonstrated that we were not just a state of Jews but also a Jewish state.

Indeed, after receiving the draft of the Declaration of Independence in 1948, Ben-Gurion restructured the opening lines numerous times to refer to the new state as a Jewish state, as a land in which our “spiritual, religious and political identity was shaped.”

Here the Jewish people “attained statehood, created cultural values of national and universal significance, and gave to the world the eternal Book of Books.” The State of Israel, the Declaration said, would be based on “freedom, justice, and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel.”

The post-Six Day War period saw the birth of what I call the moderate settler movement: Jews who danced on hilltops demanding Jewish settlements on the West Bank. In Ben-Gurion’s protégé, then-prime minister Golda Meir, they found a sympathetic ear. Although she publicly opposed them, she de facto connected all these new settlements to water and electricity and paved roads.

With the surprise rise to power of Herut and the Likud, Menahem Begin wisely spoke this new language. He understood that with the changing demography of the state, people were more comfortable seeing the State of Israel as both a state of the Jews and a Jewish state.

This new image even attracted Jews from First World countries as never before. Israel was becoming the center of Jewish life for world Jewry, even for the American Reform movement, which until 1970 had declared itself non-Zionist.

Among the Orthodox, new Zionist yeshivas were sprouting as young Jews from the United States, Canada, England, Australia, and France were coming to Israel for year-long programs and as immigrants. The religious parties were growing, and so was the traditionalist community. Political changes took place as well. The Israeli Left – Mapai and Mapam – were historically social-Zionist in the classical 20th-century sense. This meant that they were suspicious of the values preached by Western capitalist countries.

In the 1960s, Golda Meir was opposed to an Israeli television network, arguing that it would just import shallow Western Hollywood values. In the end, she allowed only news programs and educational television for children.

However, the new Left aborted socialist ideals and instead wanted the state to pattern itself after American and Western European values, making Israel a part of this larger community. Zionism was tolerated as long as it harmonized with the liberal values of the West.

The new Left gained influence after the Lebanon War and eventually dominated the Labor Party. By the 1990s, they rose to power represented by a centrist, Yitzhak Rabin, who was considered a moderate politically and a hawk militarily.

The passing of the Oslo Accords, which were voted in on a single vote in the Knesset, came as a shock. Even voters of the Labor Party were surprised to see Labor adopt the platform of the Meretz Party but gave it a chance.

The failure of the Oslo Accords created a new Israeli Right, which wanted a government that would reflect the values of Israel as a Jewish country. From the 1980s, this change began to be felt with the rise of the Shas Party, which drew more and more traditionalist Mizrahi Jews to its fold.

The National-Religious Party replaced the leadership that had previously collaborated with Labor and replaced it with Religious Zionists who saw themselves as the new pioneers of Zionism. The Agudat Yisrael Party grew naturally as a community, aided by a new aliyah of ultra-Orthodox Jews from around the globe.

The modern divide in Israeli politics

The Likud distanced itself from its revisionist past and now catered to traditionalists and the new pioneers to meet the changing social demands. This created a new dichotomy of ideals in Israeli society and a new Right and Left in politics.

More recently, there have been some interesting developments. The new Left now contains centrist elements that identify with both the traditionalists and the new Left and their Western values. In the Right camp, there are also many who have no problem with Western values if these are not antagonistic to what are seen as “Jewish” values.

The term “Jewish and democratic state,” not found in the 1948 Declaration of Independence, has become a widely accepted political affirmation for both the centrist Right and the centrist Left. However, both terms are understood by each side differently.

The Right understands “democracy” as a form of government based on the general will of the people as Rousseau termed it; and “Jewish” means a state with a Jewish majority and one that is based on Jewish values to some extent.

The further Right one identifies religiously, the more one tends to feel the state should be imbued with Jewish values. The Left, in its extreme form, sees the term “democracy” not just as a form of government but as a value system. It is a euphemism for “Western liberal values.”

“Jewish state” refers to a state where Jews live and are protected. The more centrist Left is willing to accept certain Jewish values if they do not curtail personal freedoms.

At the end of the day, the political views of most Israelis hover around the centrist ground, whether Right or Left. It is thus possible and incumbent upon these groups to meet on common ground. Only real dialogue and understanding, not empty slogans, can bring the country together. The demonstrations of the Left and the rallies of the Right serve only to destabilize the country.

In the Diaspora, this type of problem never existed. Secular Jews never had to bump into religious or haredi Jews, and religious Jews did not need to include secularists in their way of life. The ingathering of exiles in Israel has brought both blessings and challenges. We live here in the same boat, even if on different decks and in different cabins. We have no other option but to get along. We all have to understand that every single one of us has a right to be here.

AS I WRITE this article, the Knesset just passed a law limiting the Supreme Court’s use of the “reasonableness” standard. Those familiar with this concept know that it is a minor issue that was included in the president’s compromise proposal, but some on the Left fear what the future could bring. Some on the Right argue that attempts were made to reach a consensus and when this failed, they persisted in passing just one part of the reform.

This is not only legal under Israeli law but has two precedents: When the Rabin government in 1993 passed the Oslo Accords, which entailed a significant change to the borders of Israel and the creation of a Palestinian state, it passed by a single vote. In 2005, prime minister Ariel Sharon, after losing a referendum on the Disengagement Plan from his own voters, railroaded it through with a majority of his ministers, leaving 9,000 citizens homeless.

Personally, I believe that it is wrong for any party to make such major decisions that alter either the accepted norms or the borders of the country without a referendum, or at least a broad consensus.

Concerning the present judicial reform, only broad consensus will serve to defuse the situation.

The issue of judicial reform has been on the table since 1995. The Likud argues that the court changed the rules in its favor 30 years ago.

However, 30 years is a long time. Even changing things back to the way they were is a change, and Israelis have the right to an explanation. This was never forthcoming, and the anti-Netanyahu movement capitalized on it, promoting fears of a totalitarian society and creating near-mass hysteria among the more Left-leaning groups in Israel.

Therefore, at this point, it does not matter who is right, but it is important that no side “wins.”

We need broad agreement, to the chagrin of both sides, in order to create peace.

In addition, the first member of the Israeli opposition who successfully forges a sustainable agreement and helps calm the public’s fears will be the next leader of the Israeli Left. People love a leader who can dispel their fears.

Going forward, we need a new social contract in Israel. We need to discuss the future of the state and how to balance a Jewish state with personal freedoms. We also need real leadership on the Right and on the Left, one that does not see the political arena as a place to win or lose, but as a place to propose a vision of the future.

Our diversity is our strength, and our ability to unite is our secret of longevity as a people. This is the call of the moment. Who will rise to the challenge?

Raphael Shuchat, PhD, is a rabbi and senior lecturer at Bar-Ilan University.