When Pinchas Rutenberg first switched the lights on in Tel Aviv’s Allenby Street in 1923, exactly 100 years ago, he was carried through the streets by an ecstatic crowd cheering his achievement. Here was the man who electrified the whole of Palestine by building a huge hydroelectric plant on the Jordan River, just south of Lake Kinneret, together with a series of diesel-powered plants in Tel Aviv and elsewhere.

He achieved all this by a mixture of drive, initiative, and chutzpa as he convinced the British Mandatory Government to grant him the concession against serious opposition in Parliament. He certainly had the whiff of Satan about him and his history as a Russian revolutionary and as an assassin certainly did not help his case. He had also plotted the killing of Lenin and Trotsky before he escaped to Palestine in 1919, none of which recommended him to Britain.

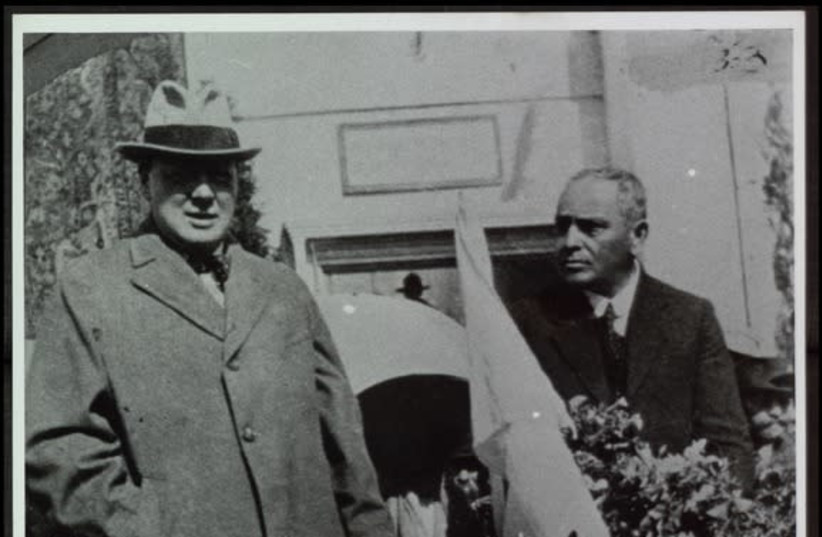

But, described as “a mixture of a steam-roller and a whirl-wind,” he managed to convince Winston Churchill and Herbert Samuel, the first high commissioner, that he was a serious hydroelectric engineer and that his plans for his generator on the Jordan would open up an arid and long-neglected land to great agricultural and industrial development. And they agreed.

Churchill, as colonial minister, pushed it through a reluctant Parliament, and by the 1930s, Palestine was almost entirely electrified by Rutenberg’s generators. Much of Mandatory Palestine’s development was dependent on his innovation. He had started life as a socialist revolutionary and now he was rapidly becoming an entrepreneur as he turned his energies to new ventures. In 1934, he set up Palestine Airways, flying regular services between Tel Aviv, Haifa, and Beirut. After the Second World War, his Airways formed the backbone of El Al.

Through hard times

HE TOOK on the leadership of the Yishuv on two occasions when the Jews of Palestine were losing faith in the Zionist Organization of Weizmann. Times were bad as the Arabs became increasingly hostile and the British Government was losing patience. He worked hard with King Abdullah of Jordan and other leading Arabs to reach some sort of agreement, but he was unsuccessful in this and in his efforts to persuade the government to make larger grants for developments in the land.

His character as a leader who brooked no argument and who was abrasive and argumentative did not help him in his political career. Ben-Gurion regarded him as politically naïve and his major achievements clearly lay elsewhere. He was An Unreasonable Man, the title of my book on him, after George Bernard Shaw’s words: “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world. The unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man” (Man and Superman).

He died in 1942 and did not live to see the creation of the Jewish state nor the destruction of his Naharayim power plant by the Jordanians in 1948.

In his will, he stipulated that no streets, towns, or villages should bear his name and no eulogies read for him when he was buried among the workers on the Mount of Olives. It may be these wishes that have seen him somewhat neglected in history. There have been but two books about him, one in Russian and another in Hebrew published some years ago, and none in English. In writing my biography of him I thought he deserved better.

An Unreasonable Man was published on Friday by Troubador.

The writer was a professor of medicine and president of the Royal College of Physicians. He is currently a member of Britain’s House of Lords. His previous books on Israel are Beyond the Balfour Declaration and Mandate: The Palestine Crucible, 1919-1939.