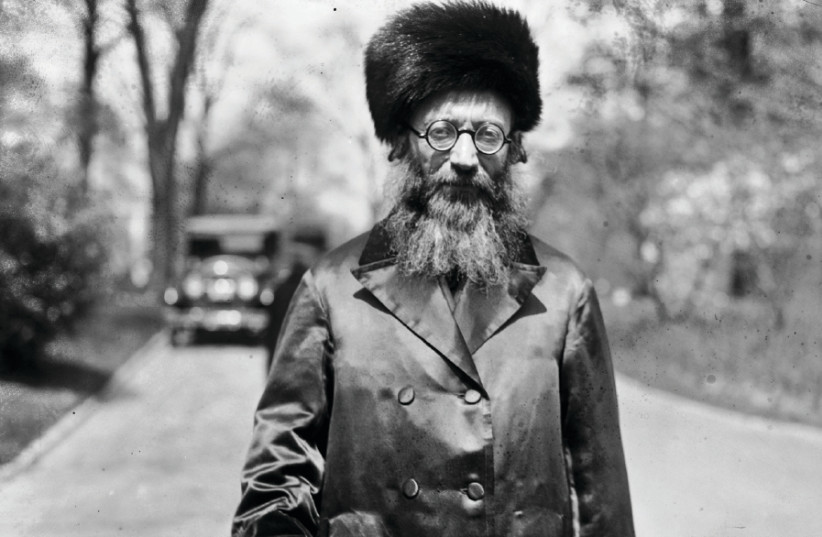

As people of faith, we often challenge ourselves to think of who is really holy and pious. In many minds, piety is often associated with someone separated from normative life, steeped in learning and religious observance. However, Rav Avraham Yitzhak Kook taught that such an image is a function of thousands of years of exile when we were stripped of statehood and collective Jewish living.

During our exile, holiness retreated into the precincts of personal life and spiritual intensity – what our sages term “the four cubits of Jewish law” – as opposed to extending also to the broader realm of societal, spiritual life. This, though, says Rav Kook, is not the ideal holiness of the Torah. This is a holiness and piety of exile and statelessness and not one that reflects the whole gamut of the spiritual life of sovereignty and statehood. One is a function of exile, the other of redemption.

The best place to examine Jewish holiness would be to look at the path blazed by Avraham, the first Jew and founding father of the Jewish people. It is Avraham’s kindness, sensitivity, and love of his family that finds expression in his pursuit of justice. In the Jewish view, holiness and righteousness are inextricably linked to collective care for society and social justice.

In our contemporary world, justice is being manifested in what can undoubtedly be described as the most just war in modern Jewish history. War – any war – is not something any moral person craves or desires; it is ugly, and every sensitive, holy person would love to avoid it. But in a world where there is so much barbarism and brutality, good people are called upon to defend themselves.

Evil happens in the world not only because of evildoers but because of the silence and impotence of the good. Avraham, as a source of goodness and blessing, could not stand by, certainly not when his own nephew, a family member, had been taken captive. He had to fight for justice and return the hostages.

Avraham, as the founding father of our people, was a man of incomparable kindness and a warrior for justice. A man of love and peace and a man of war in fighting against oppression. Avraham, Moshe, Yehoshua, and David are towering examples of Jewish holiness – scholars and soldiers, men of morality and the military. To be holy and heroic is seamlessly part of the Torah’s wholesome view of holiness.

RAV KOOK taught that when the Jewish people return to a full national life, the same holiness that appeared previously predominantly in the form of submission and obedience would appear in the form of the glory of dignity and heroism. We return to a more full and holistic Jewish life – of both personal and public aspirations of holiness.

Is the fusion between Torah and societal life, between the saintly and the soldier, something which perhaps only belongs in the era of prophecy, in the biblical era? Are we lesser mortals who live in the era of Talmudic scholars and wisdom, as opposed to that of the prophets and seers, on a lower level and therefore unable to fuse the two together?

The answer to this question is clearly given in the story of Hanukkah, which took place after the time of Tanach. Here, the Hasmoneans, or Maccabees as they became known, clearly highlight the answer.

Matityahu was an elderly kohen of the Hasmonean family and, together with his five sons, decided to declare war on the Greek occupation of Eretz Yisrael. They felt this was a situation of pikuach nefesh (life or death), affecting the very spiritual existence of the Jewish people and their Torah. The destructive decrees against Torah Judaism threatened to uproot our holy way of traditional Jewish life.

They chose not only to secretly go into the halls of Torah study and the beit midrash but to bring the beit midrash to the battlefield – to engage in a necessary milchemet mitzvah (obligatory war) and fight for the future of the Jewish people.

What is transformative about this is that they were no longer in a biblical era. The last of the prophets ceased at the beginning of the Second Temple. The Maccabees lived in the time of the Greek Empire, towards the end of the Second Temple, when prophecy had long ceased.

Yet, the same very holy and saintly priests understood that if they did not stand up for the future of Jewish destiny, there might not be a future. They took up arms in the most courageous way, as described in detail in the “Book of the Chashmonaim” (alternatively known as the “Book of the Maccabees”).

A few hundred soldiers against many thousands, then a few thousand soldiers against tens of thousands – always the few against the many. Matityahu and his family paid the ultimate price, with four of his five sons dying heroically in battle – Yehuda, Yonatan, Yochanan, and Elazar – only Shimon survived.

This is the reason we light Hanukkah candles in every household today and why Jewish destiny has continued. It is because of the courageous and heroic actions of the saintly priests and scholars who took up arms to defend their people against Syrian-Greek oppression.

The modern-day Maccabees

AFTER MORE than 14 months of battling Hamas and Hezbollah, new heroes are emerging for the Jewish people. One of many is Rabbi Avi Goldberg Hy”d (Hashem Yikom Damo, may God avenge his blood), a remarkable Jew – a mensch, an exceptional educator, and Torah scholar so deeply committed to Torah and kindness and to every detail of Halacha, while at the same time spending almost a year in reserve duty, far from his wife and children, fighting for the future of Israel.

Or like my friend and colleague Rabbi Zvi Elon, the head of the World Bnei Akiva movement, an exemplary mensch and Torah scholar and teacher. He was on reserve duty for almost 300 days, far from his wife and family, serving as both the rabbi of a brigade as well as a combat fighter as part of the brigade commander’s team.

There are so many others. This is the holiness of our generation, the holiness of sovereignty and statehood, the holiness of Avraham, Moshe, Yehoshua, Gideon, David, and the Maccabees. The holistic holiness of those who know how to combine the beit midrash with the battlefield, the beauty and sweetness of Torah learning and observance with the needs and cries of their people.

It was specifically the Maccabees who ensured that the light of Jewish destiny would continue. And it is these modern-day Maccabees, many of whom come from our Religious Zionist community, which I feel so privileged that our families are counted among them.

There can be no doubt about those who combine a life of studying Torah and aspiring for righteousness in their personal lives with heroic selflessness for the defense of their brothers and sisters on the battlefield. Are there more ultimate exemplars of piety and holiness in our painful yet most privileged generation?

The writer is the executive chairman of the World Mizrachi movement and father of fallen hostage, Captain Daniel Perez, H”yd.