Inside every person you know, there is another person you don’t. Simon Schama’s second volume of The Story of the Jews, subtitled Belonging, spanning the years 1492-1900, is an intimate, beautifully written saga of Jewish history illuminating the idea that relationships with the familiar are always more perceived than real.

Scratch the surface, and you’ll only go an inch deep. But continue digging, as this book so artfully does, and you’ll be transported to unexpected depths, revealing treasures beyond imagination.

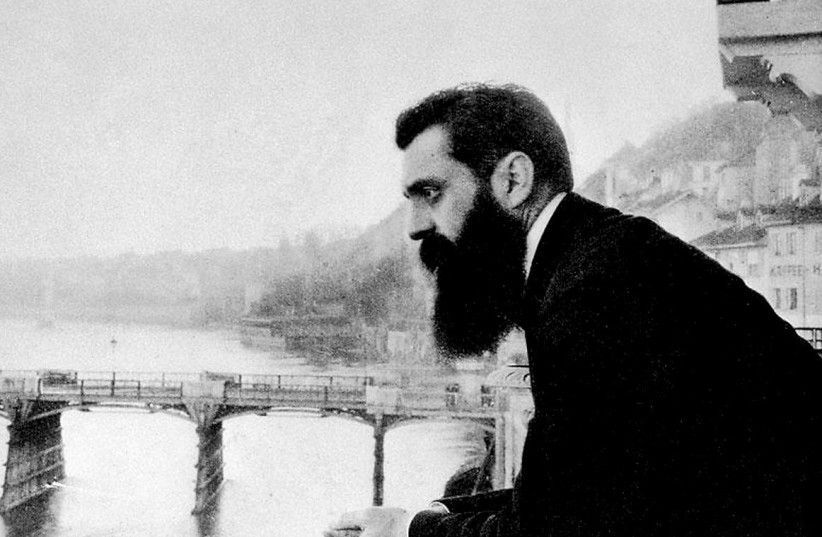

From Jewish figures with whom I was familiar – Baruch Spinoza, Benjamin Disraeli, Theodor Herzl, Moses Mendelssohn – to those I had not encountered before – Sephardi European businesswoman Gracia Mendes Nasi, protectorate of the Chinese Jewish community Chao Ch’eng, the learned Rabbi Menasseh Ben Israel, American patriot Captain Uriah Levy, and many more – The Story of the Jews: Belonging freshly introduced me to these characters who played crucial roles in shaping not only Jewish history but the history of ideas and the world.

Transitioning from chapter to chapter was akin to voyaging across Earth’s vast oceans or driving through scenic European countryside. From Berlin to Budapest, Paris to New York, Cairo to Kaifeng, Amsterdam to Odesa, London to Lisbon, Venice to Vienna, Krakow to Constantinople – all pointing to Jerusalem – readers are thrown into the whirlwind of philosophies, politics, passions, and family dramas in each city through the medieval period, the Renaissance, and modernity.

Weaving between Jewish influences and gentile responses to Christianity, Confucianism, socialism, liberalism, conservatism, and Zionism, Simon Schama powerfully demonstrates two Spinozistic ideals: the interconnectivity of all things and attaining divine potential through understanding all that one can.

Each individual, each minute characteristic, word, or action in this tale of triumph and tragedy made an impact – however subtle – that could have shifted the course of events we thought we knew.

Schama shows us that in order to understand history – and those figures we revere or despise – we must constantly dig deeper into what we do not know as well as what we already believe we know. We may never attain God’s knowledge, but reading books like Schama’s and extending our curiosity to unknown plains enables us to pose questions that propel us toward that divine stature.

Knowing more means questioning more

AS IS true with reading just a single Jewish text, Schama’s The Story of the Jews: Belonging prompted many questions. Did Judaism change the nature of antisemitism, or did antisemitism change the nature of Judaism?

Indeed, Judaism has redefined itself in response to various internal and external factors. The evolution of Judaism is as much a response to Jewish ideas as it is to the hostility from its enemies.

The deep Ashkenazi-Sephardi divide in Paris, along with the story of false messiah Sabbatai Zevi and the rabbinic uproar it caused provides an epic inside to tensions in the Jewish theological world and how gentile observers perceived the Jewish community amid their debates.

On the other hand, there were traditions shaped by hatred, such as being Jews at home and gentiles outside, continuing to wear Eastern European hockey-puck shaped fur hats after skullcaps (kippot) were banned, or building large synagogues – some that looked like churches – in urban centers of Vienna, Berlin, and Budapest out of defiance amid a period of emancipation and the Jewish enlightenment, known as the Haskala.

Schama illuminates how the story of the Jewish people is one of a deep intellectual tradition, mental wheels churning by virtue of always being on the move.

He also demonstrates that despite Jewish theological and political divisions, there is an inherent striving toward unity – not uniformity – in an effort to protect Jewish brethren and further prosperity. He illustrates the simultaneous needs of maintaining tradition, integration and acceptance, and projecting strength.

While the Jewish people have restored their homeland in Israel, belonging is still a delicate subject amid rising tides of antisemitism and tsunamis of violence. Schama assesses how intra-Jewish debates, provoked by a multitude of factors, are complex and have shaped our history to date.

Some Jews, notably those who dub themselves “Wandering Jews,” may never truly feel like they belong anywhere – not even their own home surrounded by many enemies in the Middle East. However, their unwavering spirit and contributions to the world render belonging inherent. The Jewish people have been important contributors to every society; Jewish writings, ideas, and spirit have inspired and continue to inspire civilization.

I read the last few pages of Schama’s work with hope, learning about Theodor Herzl’s tenacity to make political Zionism a reality, and hoping that Schama pens a book on modern Jewish history covering the years 1900 to today.

In an era where information is at our fingertips and we often think we know it all, Schama has the ability to deliver yet another riveting portrait of history – one that will reveal the gems of what we still do not fully understand about the Jewish story, among modernity’s accelerating advancements and ills.

During a time when perilous nationalism is conquering genuine patriotism, and instantly gratifying ticks of Instagram posts have taken over the fulfillment of comprehending our past, we are in dire need of up-close and personal histories, as Schama pens them. In his words, “A generation without history is a generation that not only loses a nation’s memory but loses a sense of what it’s like to be inside a human skin.”

The writer is a senior at George Washington University.