Symbolism over strength: Costly mistake of today’s Jewish philanthropic approach - opinion

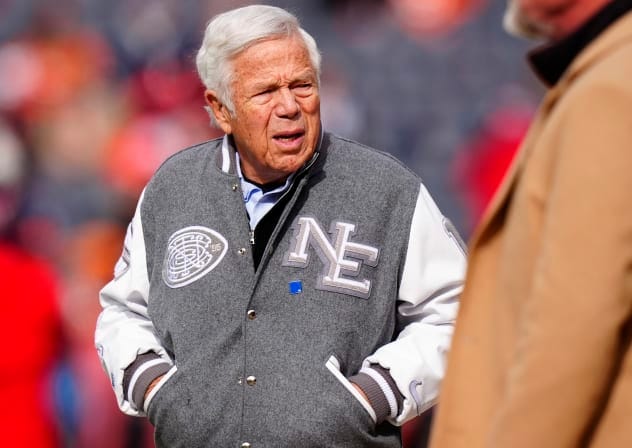

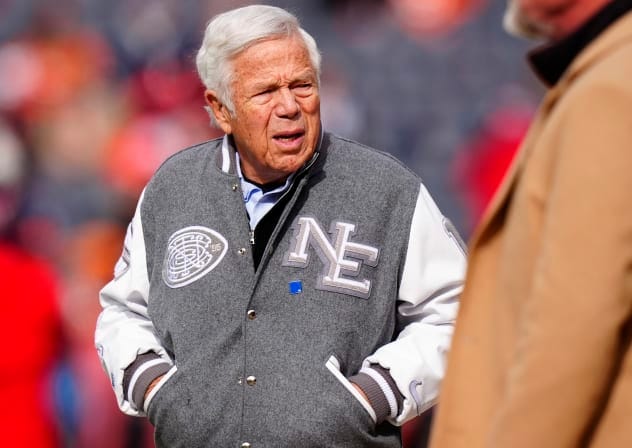

Robert Kraft's $15M Super Bowl ad depicts Jews as powerless; real survival demands strength, confidence, and self-defense, not sympathy.

Robert Kraft's $15M Super Bowl ad depicts Jews as powerless; real survival demands strength, confidence, and self-defense, not sympathy.

After October 7, not one serious Evangelical leader in the world flinched in the face of the new antisemitism, and many have doubled down in their friendship.

Her over-the-top antisemitic views seem to be an offshoot of her desire to please her Jew-hating supporters and benefactors, to the point where she even compared Israel to Nazi Germany.

Months after the twelve-day war, a systematic review of Iranian internal communications reveals that Iran copied Trump's method, refined it, and is running it back against him.

American higher education is being inundated by influence operations from Qatar, which constitute a possible national security threat.

There is a crucial fact that Western observers consistently forget: The worst violence against Iranian protesters has always occurred under so-called “reformist” governments.

On October 7, polls showed that roughly 70 percent of Gazans and 80% of West Bank Palestinians expressed support for Hamas. This is indicative of a culture in need of change.

In many ways, this makes Judea and Samaria a new Israeli region, similar to Gush Dan or Shfela, thus preventing any territorial concession, let alone the creation of a Palestinian state.

The anxieties of the 2,000s led to a plethora of dating advice explaining how to "win" in relationships. Today, open communication is prioritized.

Young Jews face a new kind of captivity: cognitive warfare eroding identity, purpose, and resilience across Israel and the Diaspora.

Israel seeks to neutralize Iran’s threat incrementally and gain operational dominance like it has in Lebanon.