The writer, a rabbi, lives in Jerusalem, where he teaches Torah inspired by the Land and her people. His forthcoming book is Return again: The argument for Aliyah.

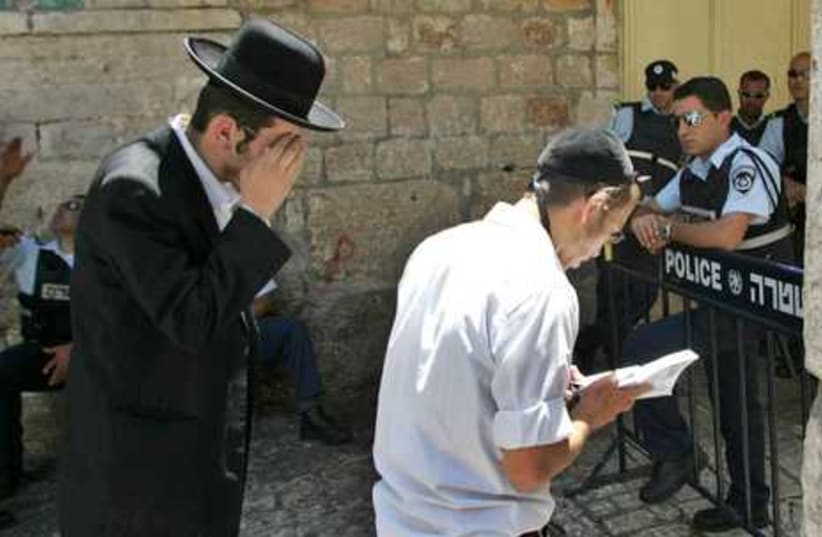

Mourning the destruction in the rebuilt Jerusalem

It didn’t feel like Tisha Be’av. Where was the sadness? The mourning? The pain? Instead, there was a feeling of triumph and victory in the warm Jerusalem air.

The writer, a rabbi, lives in Jerusalem, where he teaches Torah inspired by the Land and her people. His forthcoming book is Return again: The argument for Aliyah.