When I was a little girl, my favorite place in the world was New York’s American Museum of Natural History. We would visit my grandparents in Brooklyn several times a year, and my father and I would always find one afternoon to take the subway into Manhattan to spend a few hours there. I loved the iconic giant whale, the full scale dinosaurs, and all the living displays and dioramas, where we would talk about what life was like in America before the Europeans arrived. Eventually, the afternoon would wane, and it would be time to leave, and I’d always say the same thing “I don’t want to leave, I love it here.” My father would smile and respond “No worries, kid. That’s the great thing about a museum. It’ll always be here for you when we come back!”

I’ve been thinking a lot about those outings with my father lately, and I wonder if that statement will continue to ring true in the months and years ahead. Philanthropists, whom I speak with regularly, are feeling nervous. They’re worried, as we all are, about our own backyards; our families, neighborhoods, cities and states. People are directing their gifts, understandably, to first responders, or to Federations or directly to institutions that serve the most vulnerable. Make no mistake, this isn’t a criticism of that kind of support. I only offer a gentle reminder about why museums matter, and why financially supporting them during this time remains important.

There is significant historic precedence for supporting arts and cultural organizations during times of significant economic and global crises. Between 1933 and 1943, the US federal government supplied support to artists, musicians, actors, writers, photographers, dancers, and museums. Never before or since has America so extensively sponsored the arts. Dorothea Lange, Jackson Pollack, Lee Krasner, Willem de Kooning, and countless other artists were able to create and support themselves during a decade where otherwise, creating art and exhibitions of art wouldn’t have been possible. Museums of course were key agents in shaping and introducing art and artists in every medium to the public.

Most museums worldwide (Jewish and otherwise) have made extremely difficult decisions about their staffs, cutting salaries and positions, impacting CEOs, curators, janitors, and more. These institutions are currently earning zero revenue and largely unable to fund-raise at this time. If this continues, it is a likely scenario that exhibitions won’t be viewed, staff will lose their jobs in massive layoffs, and many of the smaller Jewish museums won’t survive at all.

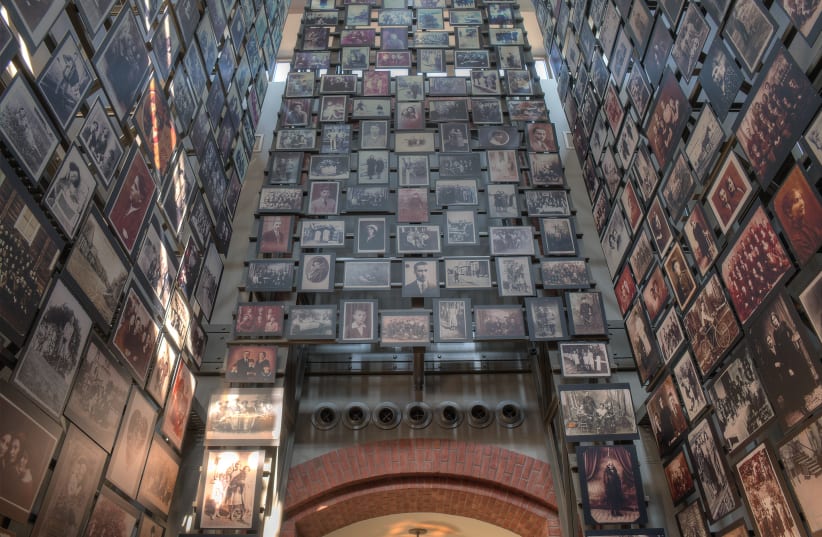

Across the diaspora, Jewish museums present cultural history in the context of the values and dynamics of their societies, with references to the past in a contemporary context. They have for decades served as a gathering place for groups (often undeserved) whose stories are told within. When I was the CEO of the LA Museum of the Holocaust, it was a nexus for survivors from Beverly Hills to Berlin to Bulgaria to come together, have a cup of tea and talk or get help filling out their Article II paperwork, or meet and mingle with visitors and students. They are in essence, community centers with galleries of history and art, of sight and of sound.

It is the multi-generational structure inherent in museums that makes them unique as all-inclusive family spaces. Museums shape the experience of all people, and open their eyes to new ideas. There is virtually nobody I know that hasn’t had a life- altering experience at a museum. I vividly remember seeing models in the Museum of the Jewish People, Beit Hatfutsot’s Synagogue Hall as a teenager on my very first trip to Israel. I saw Amsterdam’s great Portuguese Synagogue, and realized that I could pinpoint the very window through which a survivor whom I knew well from my hometown leaped to his freedom from the Nazis. I always think about it when I walk through that hall – even now, 30 years later, where I’m fortunate to work.

There is enormous interest in Jewish museums globally. Many have annual visitors upwards of half a million, most of whom are not Jewish, and often, their visit may be their first and possibly only touch point with Jews or Judaism. The largest groups that visit museums in Israel now mirror those figures and show that Chinese, Evangelical Christians and other non-Jewish ethnic groups flock to the museums of Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Haifa and throughout the country. According to market research, the average diaspora Jew patronizes four museums annually, and takes their travel opportunities for both business and pleasure to visit a museum in the city, state or country they are visiting. In the cases of Jewish museums, that number increases.

Once this crisis passes and life returns to normal, if we lose our cultural spine we will lose much more then we’ve already lost. Museums perform services that we cannot afford to let slip away and cannot be served on an iPad. Nothing replaces the moment of seeing your first well-lit Chagall painting in an echoing hallway, or when you proudly show your grandson the displayed jersey worn by your baseball hero, Sandy Koufax. Those whose stories are told within always want to be there for you and yours when you return.

The writer is the VP of MJP, Beit Hatfutsot International, and previously was the CEO of Jewish museums such as The LA Museum of the Holocaust and The American Jewish Historical Society.