Background

On February 9, 2019, Turkey’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement harshly criticizing China’s policy toward the ethnically Turkic Uyghur population in China’s Xinjiang Province, reversing a three-year policy of conciliation toward Beijing on the Uyghur issue. Belatedly castigating China’s October 2017 adoption of its “Sinification of All Religions and Beliefs” policy as a program for “eliminating the ethnic, religious and cultural identities of the Uyghur Turks,” Turkey’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson declared, “It is no longer a secret that more than one million Uyghur Turks incurring arbitrary arrests are subjected to torture and political brainwashing in internment camps and prisons.” Decrying Beijing’s actions as a “great shame for humanity,” Turkey’s Foreign Ministry officially called upon “on the international community and the secretary-general of the United Nations to take effective measures in order to bring to an end this human tragedy in Xinjiang.”

The precipitating event for the astounding policy turn-around seems to be the reported death of Abdurehim Heyit, who was imprisoned by Chinese authorities. A revered poet and performer of traditional Uyghur music, Heyit is a symbol of the struggle to preserve the Uyghur cultural heritage. A bridge between Uyghur and Turkish cultures, Heyit has a large following in Turkey, where he performed just prior to his 2017 arrest. The foreign ministry explicitly mentioned the singer by name and its sorrow over Heyit’s death.

However, to Turkey’s embarrassment, China Radio International’s Turkish-language service released a video dated February 10, 2019, in which a man appearing to be Abdurehim Heyit speaks in the Uyghur language and states that he is in “good health.”

In her February 11 press briefing, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chun attempted to undermine the legitimacy of Ankara’s protest over Beijing’s treatment of Xinjiang’s Uyghur population. Focusing on the erroneous claim that Heyit died in Chinese custody, she declared, “Turkey made groundless accusations against China based on the absurd lie of portraying the living as dead. This is extremely wrong and irresponsible, and we firmly oppose it.”

The following day the Chinese government issued a travel advisory admonishing its citizens against traveling to Turkey. China’s Ankara Embassy warned Chinese residents and tourists in Turkey to “be wary and pay attention to their personal safety.” While a legitimate concern, given the past history of popular anti-Chinese violence in Turkey, including attacks on travelers from other East Asian nations mistaken for being Chinese, Beijing’s advisory targets Turkey’s tourism industry at a time when the country’s economy is fragile. While the overall impact to Turkey’s tourism will likely be small, the advisory also serves as a warning shot from Beijing that is prepared to retaliate economically for any further Turkish action.

Implications

As China’s gateway to Central Asia, Xinjiang is a critical launching point for Beijing’s effort to create its Silk Road Economic Belt, an overland transit corridor for China-to-Europe trade (the “Belt” of China’s massive Belt-and-Road Initiative, or BRI). Announced by Chinese President Xi Jinping in October 2013 in Astana, Kazakhstan, Beijing has already invested over $250 billion in Central Asia. Beijing seeks to rapidly develop its vast northwestern Xinjiang Province to secure its integration within China and the projection of Chinese hegemony westward across Central Asia. Formerly a majority in what many Uyghur nationalists refer to as “East Turkestan,” Turkic Uyghurs now constitute 45% of Xinjiang’s population, due to the heavy migration of ethnic Han Chinese as part of Beijing’s development program.

China casts a wary eye at Turkey as the center of pan-Turkic activism that threatens Beijing’s interests in Xinjiang and Central Asia. Turkey is home to the Cooperation Council of Turkic-Speaking States (TURKSOY), and of more immediate concern to China, a sizeable and highly active Uyghur expatriate community.

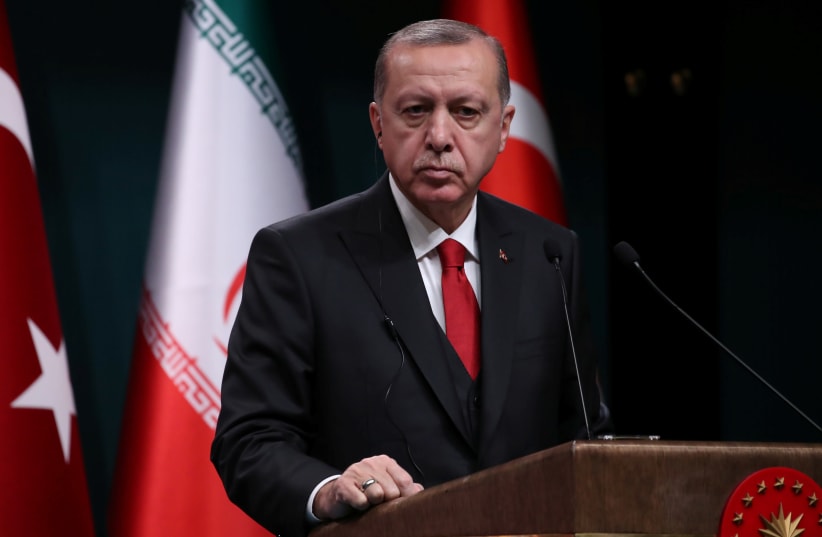

As mayor of Istanbul in 1995, now Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan built a memorial monument to Isa Yusuf Alptekin, leader of the short-lived East Turkestan Republic, defying a Turkish government ban and Chinese protests. In 1992, then Turkish President Turgut Ozal and Alptekin declared, “Turkic republics under former Soviet rule have all declared their independence. Now it is Eastern Turkestan’s turn. It is our desire to see the ancient homeland of the Turkic people a free country.” As prime minister, Erdogan harshly condemned China’s suppression of the July 2009 “riots” in Xijiang’s capital Urumqi, and publicly declared China’s actions to be “a kind of genocide.”

Following this nadir in Sino-Turkish relations, Erdogan attempted to mend relations with Beijing. In the period after Turkey’s June 2011 elections, as Erdogan sought to consolidate his power in a new presidential system, Turkey distanced itself from its Western allies and embraced a closer relationship with China, positioning itself as a partner for China’s BRI.

In the wake of renewed anti-China protests in Istanbul in 2015, Erdogan traveled to Beijing to meet with his Chinese counterpart to smooth over tensions, particularly after it became known that Turkish diplomats in Thailand assisted Uyghur refugees to obtain safe passage to Turkey. In China, Turkey’s president pledged his support for China’s territorial integrity. At that point, Ankara was still in discussions with Beijing to obtain a $3.4 billion Chinese anti-missile system, only later to settle on the Russian S-400 system.

In May 2016, Ankara demonstrated its increasing willingness to accommodate Beijing when, in contrast to its usual practices concerning Uyghur refugees, Turkey arrested 98 Uyghurs with forged passports en route to Saudi Arabia. After the failed July 2016 coup attempt against Erdogan’s government and the resultant authoritarian crackdown, Turkey drew even closer to Beijing, amid criticism from Western capitals over the erosion of civil rights in Turkey.

By 2018, Ankara’s accommodation of Beijing seemed to pay off, with an infusion of desperately needed foreign capital. On July 26, 2018, Turkey’s Treasury and Finance Minister Berat Albayrak announced that the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) agreed to provide a $3.6 billion loan package for Turkey’s energy and transportation sectors. The loan was apparently the result of negotiations held with the state-owned ICBC during Albayrak’s May 2018 visit to China.

Accordingly in late 2018, Erdogan’s AKP government rejected a parliamentary motion brought by the Iyi (“Good”) Party to investigate human rights violation allegedly perpetrated by China against the Uyghurs. The center-right, nationalist Iyi Party broke away in 2017 from Turkey’s main nationalist party, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), the coalition partner that provides the AKP with a ruling majority in parliament.

The Iyi Party, along with the extreme Turkic nationalist Great Union Party (BBP) and other minor parties, began highlighting the AKP’s reluctance to speak out on the Uyghur issue, undermining the image of the AKP among a segment of the nationalist vote before Turkey’s March 31 nationwide local elections. On January 24, 2019, the BBP held a large rally to protest the AKP’s inaction over the oppressive conditions faced by Uyghurs in Xinjiang. The rally was the culmination of a series of smaller events that have been held in nationalist strongholds across Turkey during the last several months and created pressure for Erdogan’s government to act decisively before the issue siphoned off support among disgruntled nationalist voters already disaffected by the poor state of Turkey’ economy.

Conclusions

Most of the Middle East has been silent on China’s treatment of Xinjiang’s Uyghurs, fearing to risk its relationship with Beijing, particularly as US interest and influence in the region seems to be waning. China is the world’s largest importer of both oil and natural gas, thus constituting a critical export market for Middle Eastern hydrocarbons.

In the Eastern Mediterranean, Beijing also forms a crucial source of foreign infrastructure investment, especially for Turkey’s rivals Egypt and Greece. China has invested $35 billion in the construction of the Egypt’s new capital. Having transformed Greece’s Piraeus Port into one of world’s state-of-the-art container ports, Beijing now owns and operates one of the European Union’s major seaports, making Greece a major hub for Chinese goods to enter European markets.

Despite China’s 2014 completion of an Ankara-to-Istanbul, high-speed rail link, Beijing has been cautious about inviting Turkey to play a larger in the BRI, despite the country’s geographical position as a land-bridge between Asia and Europe. China’s $3.6 billion loan package in 2018 seemed to indicate that Ankara’s three-year accommodation of China’s policies in Xinjiang had begun to encourage Beijing to reconsider the limits it has imposed on Sino-Turkish cooperation.

Turkey’s recent harsh condemnation of China will only reinforce Beijing’s apprehension that Turkish nationalism’s core element of Pan-Turkic solidarity poses an enduring threat to Beijing’s vital interests in Xinjiang, and its strategic ambitions across Turkic Central Asia. In his seminal 2013 article on Turkish-Chinese relations, Yunnan University Prof. Xiao Xin summarizes the Chinese apprehension: “Given Turkey’s political trend, one can never be certain about its stance on ‘Eastern Turkistan.’” As long as the collision between China’s agenda in Xinjiang and Pan-Turkic solidarity forms an inherent limit to Sino-Turkish cooperation, Turkey will continue to find itself confined to a secondary role in China’s Belt-and-Road Initiative.

The writer is a fellow at the Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and an affiliated scholar with the Center for Strategic Studies at Baskent University in Ankara, Turkey. Follow @michaeltanchum. This article originally appeared in The Turkey Analyst.