Leukemia is a group of blood cancers that usually begin in the bone marrow due to a lack of normal blood cells and create large numbers of abnormal blood cells. Symptoms may include bleeding and bruising, bone pain, fatigue, fever and an increased risk of infections.

While its exact cause is unknown, a combination of genetic and environmental factors – including smoking, ionizing radiation, exposure to some chemicals, such as benzene, having had chemotherapy, and Down syndrome – are believed to play a role.

Although it is the most common type of cancer in children, more than 90% of all leukemias are diagnosed in adults.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if, somehow, highly proliferative leukemia cells that grow and multiply rapidly could revert to normal cells that no longer multiply? Like putting a jack-in-the-box back into the container.

New research led by scientists in Barcelona, Spain – with significant participation by colleagues at the Department of Human Genetics and Biochemistry of Tel Aviv University’s Sackler Faculty of Medicine: Prof. Gideon Rehavi, Nitzan Kol, Chen Avrahami and Sharon Moshitch-Moshkovitz – has managed to do this. They have just published their findings in the high-impact journal Leukemia under the title, “Remodeling of the m6A RNA landscape in the conversion of acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells to macrophages.”

The article describes how leukemia cells become normal cells that no longer multiply by changing the chemical modifications – the so-called epigenetics – of a type of its genetic material called messenger RNA. The Spanish participants included Alberto Bueno-Costa, a researcher with the group of Dr. Manel Esteller, who heads the Josep Carreras Leukemia Research Institute at the University of Barcelona.

After much research

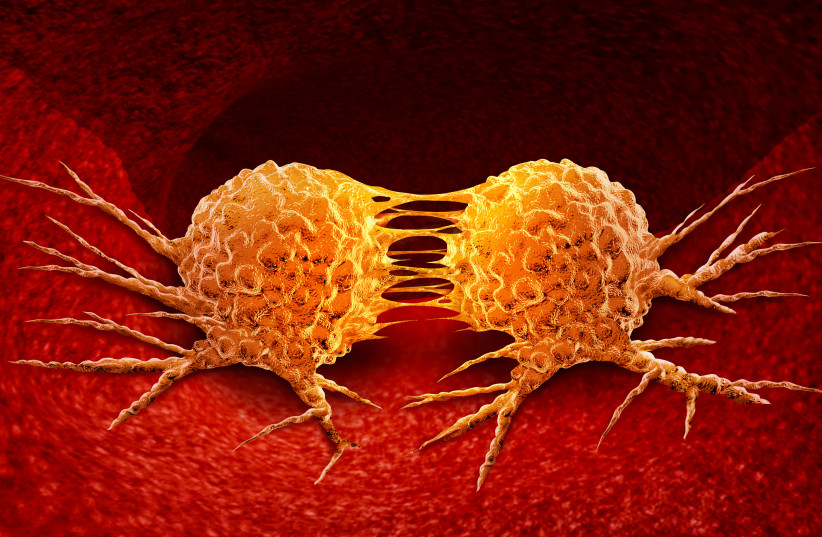

In cancer, healthy cells turn into malignant ones with very different characteristics, such as the ability to divide in an uncontrolled manner. In recent decades, much research has uncovered various molecular alterations responsible for this conversion from healthy to tumor tissue. But until now, scientists have known very little about the opposite process – reversing a cancer cell, turning it into a physiological, noncancerous one, and what factors might mediate this process.

“We know that one strategy that human tumors have to dodge the effectiveness of drugs is to change their appearance, becoming another similar cancer but insensitive to the drug used,” the team said. “For example, leukemias of the lymphoid lineage are switched to the myeloid strain to escape treatment.”

With this idea in mind, they wanted to know more about the molecular pathways involved in this cellular transformation. They studied an in vitro model (experiment performed outside of a living organism, usually in a test tube or petri dish) in which leukemia cells can be forced to turn into a type of harmless immune cells called macrophages.

Experimental results showed that the reversal of the malignant cells into macrophages involved a tremendous revision in the chemical changes occurring on their messenger RNA – the carriers that help proteins form. The changes especially affected the distribution of an epigenetic mark named methylated adenine.

This change in the angle formed between two adjacent chemical bonds of these molecules causes instability of the proteins that define the leukemia, while favoring the appearance of microphages – proteins characteristic of the normal cells that are being born.

Although this line of research has not yet been tried on patients, the team said it seems quite promising and is worth further exploration as a new approach in the fight against leukemia. The more strategies developed to fight leukemia, the more hope there is for the half a million patients around the world who are diagnosed annually with blood malignancies.

Perhaps, turning leukemia cells into harmless types will eventually be part of oncologists’ and hematologists’ arsenal against cancer.

“The first preclinical drugs against this target have already been developed in experimental models of malignant blood diseases, so we provide another reason why these novel drugs could be useful in cancer therapies, particularly in the case of leukemias and lymphomas,” Esteller said. -