An asteroid once feared as "the riskiest asteroid known to humankind" for having a likely shot at impacting the Earth in the coming decades won't actually hit us within this century, the European Space Agency (ESA) announced.

The asteroid in question, designated 2021 QM1 and estimated to be around 50 meters wide, was once feared by experts because of calculations suggesting it had a chance of impacting the Earth on April 2, 2052.

But in an announcement set right before Asteroid Day, the ESA confirmed that its team of experts, working with researchers at the European Southern Observatory (ESO), have concluded that 2021 QM1 won't hit the Earth for at least another 100 years.

But what's amazing about this discovery isn't just that it ruled out a potential impact risk, but how they were able to get the data needed to do so, resulting in an intense hunt for an elusive asteroid.

"The riskiest asteroid known to humankind"

The asteroid 2021 QM1 is estimated to be around 50 meters wide, just around the size of the famous Arc de Triomphe in Paris, and was first discovered in 2021 by researchers at the Mount Lemmon Observatory in Arizona. At first, nothing seemed out of the ordinary. Just another asteroid along with the over 1 million known to exist in the solar system, orbiting alongside the planets around the Sun.

Follow-up observations gave more info. For instance, it was determined that 2021 QM1 is an Apollo-class asteroid, meaning its orbit around the Sun overlaps with Earth's own orbit. This also isn't anything new, and there are tens of thousands of Apollo-class asteroids out there. In fact, they are the single most common type of near-Earth objects (NEOs).

Soon, calculations determined that it could be seen as a possible risk for an impact in the future. This, too, isn't too unusual. Calculations like this are usually done very quickly so they often get put on risk lists upon discovery. But soon, more data gets gathered, more calculations are done to narrow the scope of the orbit and then we become more sure of an asteroid's given orbit. Then, scientists are able to determine it isn't as risky as initially thought.

But as more follow-up observations came in from other observatories around the world, it began to paint a more ominous picture.

“We could see its future paths around the Sun, and in 2052 it could come dangerously close to Earth. The more the asteroid was observed, the greater that risk became.”

Richard Moissl

“We could see its future paths around the Sun, and in 2052 it could come dangerously close to Earth,” noted ESA planetary defense chief Richard Moissl.

“The more the asteroid was observed, the greater that risk became.”

With the risk rising, it became imperative to gather more data.

But just when we needed the data most, the asteroid vanished, its orbit taking it closer to the Sun, with the bright sunlight obscuring 2021 QM1 for months.

Not only that, but it was also moving away from the Earth.

“By the time it passed out of the Sun’s glare, it could be too faint to detect,” ESA Near-Earth Object Coordination Centre (NEOCC) astronomer Marco Micheli explained.

But that doesn't mean astronomers were out of options. When there's a will, there's a way: And in this case, the way was a very large telescope known as the Very Large Telescope (VLT).

The hunt is on

The VLT is a special telescope facility operated in northern Chile and is one of the most advanced and productive astronomy facilities in existence. Since its inception, it has led to numerous scientific discoveries and in its observations of the greater cosmos, such as the first direct imaging of an exoplanet (a planet outside the solar system).

In fact, according to a 2010 estimate, among all telescopes operating at visible wavelengths, only NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has produced more published scientific research.

And to hunt down 2021 QM1, the VLT may be exactly what scientists needed.

They didn't have much time, though. The VLT was ready and waiting so it could spot 2021 QM1 the moment it emerged out of the obscuring glare of sunlight – weather permitting, of course.

“We had a brief window in which to spot our risky asteroid,” explained Olivier Hainaut, Astronomer at ESO.

“To make matters worse, it was passing through a region of the sky with the Milky Way just behind. Our small, faint, receding asteroid would have to be found against a backdrop of thousands of stars. These would turn out to be some of the trickiest asteroid observations we have ever made.”

“To make matters worse, it was passing through a region of the sky with the Milky Way just behind. Our small, faint, receding asteroid would have to be found against a backdrop of thousands of stars. These would turn out to be some of the trickiest asteroid observations we have ever made.”

Olivier Hainaut

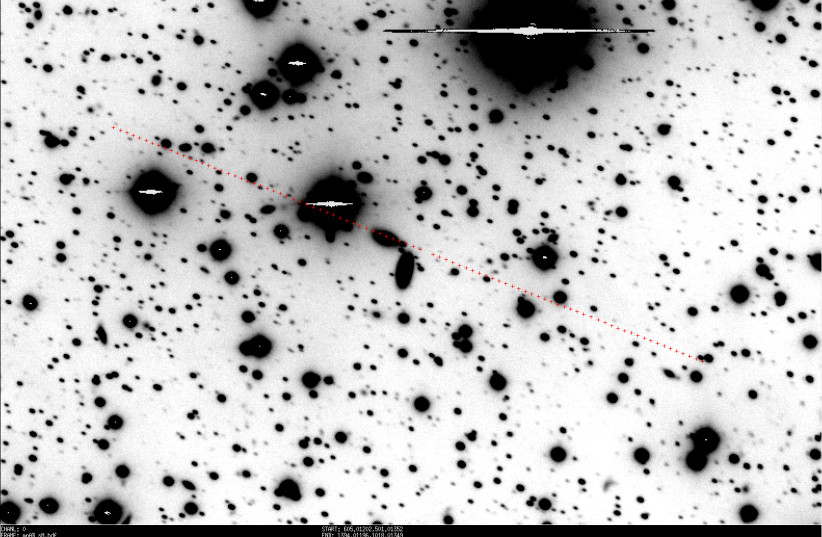

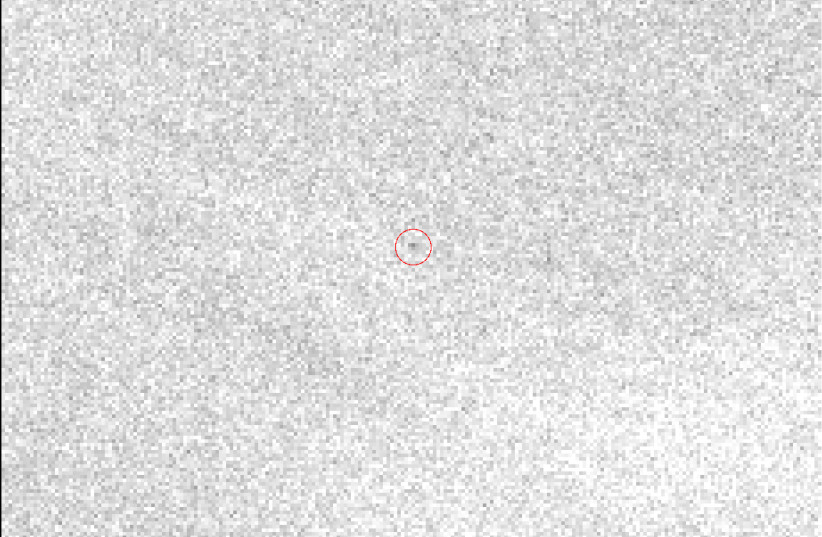

But on May 24, the VLT had the asteroid in its sights, and it took the shot.

Over the course of the night, a series of new images of the asteroid was taken and the scientists got to work sifting through it all, processing the many observations and isolating it away from background stars.

The result was the image of the faintest asteroid ever seen. Indeed, the sheer level of faintness was nothing short of astronomical, being 250 million times fainter than the faintest stars visible to the naked eye.

Now the hunt was over, and it was time for the math to begin.

Safe at home

The calculations spoke for themselves. While 2021 QM1 is still a NEO and an Apollo-class asteroid, it's no longer considered risky and is now off the list of ESA's risky asteroids, though 1,377 other asteroids are still on the list.

Keep in mind that even if the asteroid did strike the Earth, it wouldn't be the literal end of the world.

According to research from the Davidson Institute of Science, the educational arm of Israel's Weizmann Institute of Science, an asteroid over 140 meters in diameter would release an amount of energy at least a thousand times greater than that released by the first atomic bomb if it impacted Earth.

Something even larger — over 300 meters wide like the asteroid Apophis — could destroy an entire continent. An asteroid over a kilometer in width could trigger a worldwide cataclysm.

As 2021 QM1 was just around 50 meters wide, it wouldn't be nearly as bad as the others. But it could still cause considerable damage.

For an example, look at what occurred on February 15, 2013, when an asteroid exploded in the air above Chelyabinsk, Russia. This asteroid was around 17 meters wide, and while it didn't result in any casualties, the shock wave from the explosion shattered windows in six different Russian cities and caused 1,500 people to require medical attention.

Likely, 2021 QM1 would have been worse, if it ever hit.

The last truly catastrophic asteroid impact to strike the Earth was in 1908 in an incident known as the Tunguska event.

That was when an asteroid, thought to be around 190 meters wide, exploded in the air several kilometers above the area of the Tunguska River in Russia, it produced a massive 12 megaton explosion, causing widespread destruction for thousands of kilometers. That would make it about 800 times more powerful than "Little Boy," the approximately 15-kiloton atomic bomb detonated during World War II over Hiroshima, and 600 times more than "Fat Man," the 20-kiloton one detonated over Nagasaki three days later.

Incidentally, the Tunguska event is commemorated every year on June 30, its anniversary, as the UN-proclaimed Asteroid Day.

This day is made to promote awareness of asteroids and for scientific advancement in the field of planetary defense, such as advancing tracking of asteroids and for defending the Earth against them.

This is important since an asteroid impact is one of the single most devastating possible natural disasters that could occur.

Even now, scientists have continued to advance methods of asteroid detection and defense, including NASA's groundbreaking Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission that is set to test the possibility of asteroid deflection.