The countries surrounding the Red Sea don’t always get along, but there is an iconic and endangered ocean creature – the manta ray (Mobula birostris) that needs their help to survive and thrive. Surprisingly little is known about this species, which looks like the deadly stingray but is very different.

Manta rays don’t have barbs with serrated edges and venom, so they are not dangerous like stingrays, whose poison can even kill humans. Mantas have a mouth located underneath their body, manta rays use their gill rakers to filter out zooplankton from the water; even though they are huge, they feed on tiny organisms and not fish. Stingrays fed on much larger animals, from claims and shrimp to squid.

Mantas and stingrays live all across the ocean in warm regions, but mantas – unlike stingrays – can’t live in freshwater. Manta rays are much larger and, thanks to their huge brains – are smarter, while their legal “cousins” are more aggressive.

“I wanted to learn more about the Red Sea manta population, but a full scientific survey would be challenging and expensive. I realized we could tap into social media for help.”

Anna Knochel, a former master’s degree student at the university who led the project under supervision

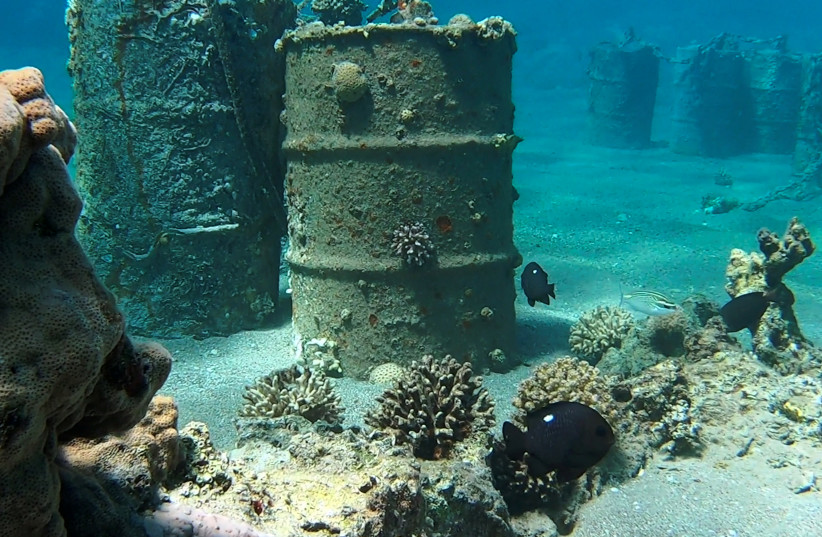

Now, a study led by researchers at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia has provided insights into population demographics and the movement of these rays across the Red Sea region. It also hints at a potential nursery ground off the Egyptian coast of Sharm El-Sheikh.

“There are so many unknowns about these charismatic creatures,” said Anna Knochel, a former master’s degree student at the university who led the project under the supervision of Michael Berumen. “I wanted to learn more about the Red Sea manta population, but a full scientific survey would be challenging and expensive. I realized we could tap into social media for help.”

Analyzing manta sightings

She and her team began by collating images and details of sightings they had witnessed. “Like whale sharks, manta rays have unique spot patterns on their bodies; this, together with size estimates gleaned from photographs, meant that individuals could be identified,” Knochel continued.

“These findings will encourage further research into oceanic manta rays, and Saudi Arabia has a real chance to model best practice in terms of sustainable tourism for marine wildlife.”

Michael Berumen

The team identified 267 mantas from 395 sightings in Egypt, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and Jordan between 2004 to 2021. The movements of 21 rays that were sighted in more than one location – including basin-spanning migrations from one side of the Red Sea to the other – were recorded. The ability of these animals to undertake long-distance movements over deep water means that multinational cooperation will be required to protect them effectively, she noted.

“I noticed that many of the rays were really young; they were small, and I could see juvenile males with immature sexual organs,” said Knochel. “I identified 27 young males and estimate that a further 29 were juvenile females. The young rays were regularly spotted at Sharm El-Sheikh, suggesting that the area could be a nursery ground.”

The only other known nursery ground for oceanic manta rays is the Flower Garden Banks, a marine sanctuary in the Gulf of Mexico, where sightings of juvenile males were confirmed in a recent paper.

“This study highlights the untapped value of the Red Sea, not just to scientists, but to all the nations surrounding its coasts,” says Berumen. “These findings will encourage further research into oceanic manta rays, and Saudi Arabia has a real chance to model best practice in terms of sustainable tourism for marine wildlife.”