Scientists managed to discover what may be one of the single largest black holes ever discovered, a new study revealed.

The discovery of this black hole, at the center of Abell 1201 BCG, was made by use of a technique known as gravitational lensing and is in fact the first black hole ever found this way.

The findings of this study were published in the peer-reviewed academic journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The black hole itself is classified as a supermassive black hole, which is in theory the largest kind of black hole. However, this one is so big that it may be in an even greater league: An ultramassive black hole.

Hole-y cow! What are black holes?

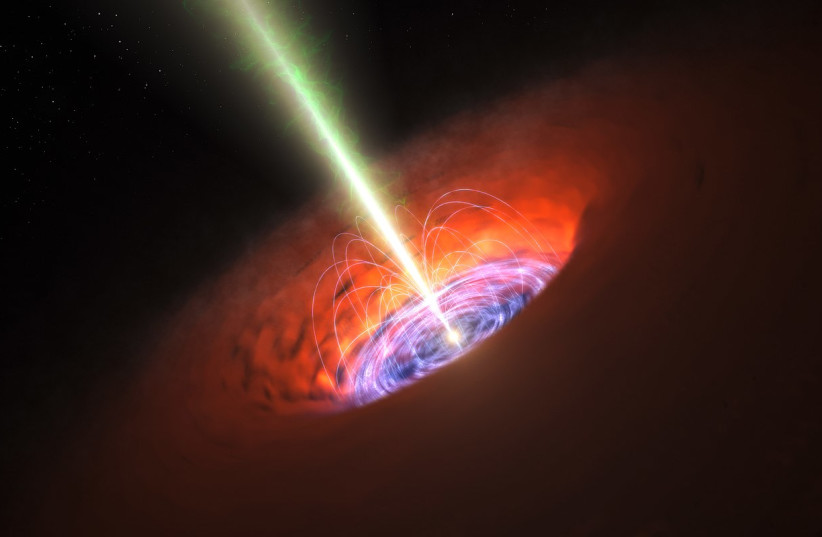

Black holes are, to incredibly simplify a complex cosmic phenomenon, massive concentrations of gravity so strong that nothing, not even light, is able to escape.

There are many of them. In fact, according to one recent study, the observable universe (which has a diameter of approximately 90 billion light-years) is home to around 40 quadrillion (40,000,000,000,000,000, or 40 x 10^18 in scientific notation) black holes.

However, they are very mysterious, to the point that scientists weren't even sure they existed 20-30 years ago. The only way we know the black hole exists is because it has an enormous gravitational pull that influences matter around it.

Supermassive black holes, however, are even larger, technically measuring at over 100,000 solar masses but could even measure millions and billions of solar masses. To put that into perspective, one solar mass is equal to the Sun.

These black holes can be found at the center of most spiral galaxies. Our Milky Way Galaxy is no exception, with the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* essentially being what the entire galaxy revolves around.

Researchers have proposed the existence of an even greater class of black hole: Ultramassive black holes.

These researchers have said that this label could apply to black holes that are larger than five billion solar masses. However, this isn't something that everyone agrees on.

At the same time, other scientists have said in the past that there is likely a limit to how large a black hole can get, specifically around 50 billion solar masses (5 x 10^10 in scientific notation). There are reasons for this, mainly due to the fact that given how black hole growth works, there simply hasn't been enough time in the history of the universe for black holes to have grown any larger than that.

So that's what a black hole is, but what did these scientists find – and how did they find it?

The power to bend light: What is gravitational lensing?

Abell 1201 isn't the name of the black hole, specifically, but rather a galaxy cluster, which is a group of several galaxies all located fairly close to one another – close being in relativistic terms to galaxies and the ever-expanding space.

Within this galaxy lies one especially large galaxy known as Abell 1201 BCG, the BCG referring to its status as the brightest cluster galaxy – a term that refers to the largest and brightest galaxies in a cluster, which many scientists have theorized form when other galaxies merge together.

And at the center of this galaxy is, like in many others, a black hole.

Now that that is established, it's important to understand how gravitational lensing plays a role.

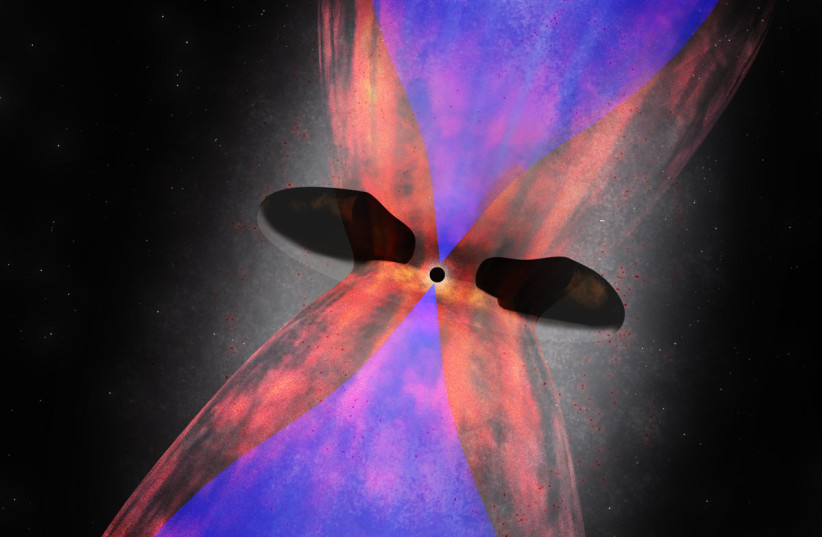

Gravitational lensing is a natural phenomenon in which the gravity of a massive body, such as a galaxy or a galaxy cluster, bends the light that is being emitted from a distant object. This allows the gravity of the massive object to act like a lens, and through this method, the light of the distant object is intensified and its shape is enlarged.

Basically, if we on Earth want to see Galaxy B, but Galaxy A is in the way, then the sheer mass and gravity of Galaxy B might be able to help by bending the light from Galaxy A so we'd be able to better look at it.

But while using data from the Hubble Space Telescope relating to Abell 1201 BCG, the researchers behind this study managed to discover an ultramassive black hole with 30 billion solar masses.

This itself is the result of nearly 20 years of prior research.

Back in 2004, researchers from Durham University in the UK first noticed that light bent in this area – something that must be the result of a gravitational lens.

However, we weren't yet able to see anything in a galaxy so far away.

The researchers behind the new study, also led by Durham University, made use of both gravitational lensing calculations and supercomputer models to try to find out how the light was bent here.

The culprit must have been a black hole, but how big? It wasn't until they calculated the impact of an ultramassive black hole in one of the simulations that the result matched the data captured by Hubble.

And massive it certainly is, with 30 billion solar masses approaching the theoretical limit.

But how did it grow so big in the first place?

"Gravitational lensing makes it possible to study inactive black holes, something not currently possible in distant galaxies," lead author Dr. James Nightingale said in a statement.

"This approach could let us detect many more black holes beyond our local universe and reveal how these exotic objects evolved further back in cosmic time."

But is this black hole even the biggest?

Currently, the most massive black hole known to science is believed to be TON 618, an extremely luminous quasar, thought to be over 40 billion solar masses, though prior estimates have given it as much as 64 billion.

And even then, some are thought to be even larger.

The most massive of these is likely Phoenix A, the black hole at the center of the Phoenix Cluster galaxy. Based on the information about it and scientific modes, it may be as much as 100 billion solar masses if not greater.

Is this even possible? Maybe. In fact, scientists have theorized that it may belong to another, hypothetical class of black holes even greater than ultramassive black holes: Stupendously large black holes. But this is still the subject of considerable debate.

But with further advancements in techniques like gravitational lensing, it isn't out of the realm of possibility that we may one day know more about some of the largest and strangest aspects of the universe like this.

Shira Silkoff contributed to this report.