For hundreds of thousands of years, prehistoric humans living in the area of present-day Israel and its surroundings hunted and fed on the largest available animals until the beasts became extinct and then the people moved on to the next biggest species, new research from Tel Aviv University scholars has shown.

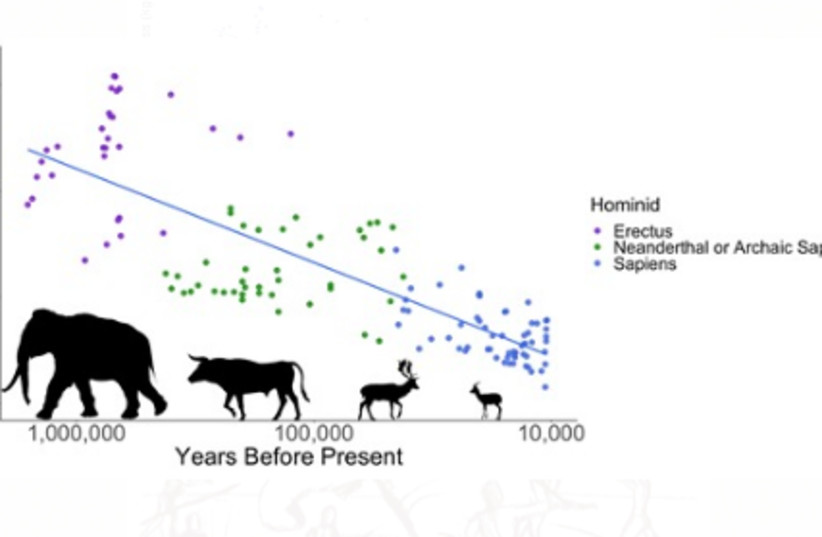

Over the course of around 1.5 million years, the ancient populations of the region consumed progressively smaller species – starting from mighty, one-ton elephants and eventually getting down to 30-kilogram gazelles. By doing so, they brought terrible disruption to the ecosystem, but they were also forced to evolve and develop new skills and technologies to capture their new sources of food.

The study – whose results were published in Quaternary Science Reviews – intended to address both issues: What caused the mass extinction of mega-herbivores, often attributed to climate change, and what fueled the extraordinary development of humans into what they are today?

“In light of previous studies, our team proposed an original hypothesis that links the two questions,” said Prof. Ran Barkai. “We think that large animals went extinct due to over-hunting by humans, and that the change in diet and the need to hunt progressively smaller animals may have propelled the changes in humankind.”

The team analyzed data from 58 prehistoric sites in the area, considering 133 layers from different time periods and thousands of bones belonging to 83 animal species.

“We considered the southern Levant (Israel, the Palestinian Authority, Southwest Syria, Jordan and Lebanon) to be an ‘archaeological laboratory’ due to the density and continuity of prehistoric findings covering such a long period of time over a relatively small area – a unique database unavailable anywhere else in the world,” said Jacob Dembitzer.

“Excavations, which began 150 years ago, have produced evidence for the presence of humans, beginning with Homo erectus who arrived 1.5 million years ago, through the Neanderthals who lived here from an unknown time until they disappeared about 45,000 years ago, to modern humans (namely, ourselves) who came from Africa in several waves starting around 180,000 years ago,” he said.

THE RESEARCHERS determined that around a million years ago, elephants twice as large as contemporary African ones, comprised 90% of the food of early humans (Homo erectus). Elephant bones represented approximately a third of the remains found at the sites from the period and bones were present in almost all sites up to approximately 500,000 years ago.

“Starting about 400,000 years ago, the humans who lived in our region – early ancestors of the Neanderthals and Homo sapiens – appear to have hunted mainly deer, along with some larger animals weighing almost a ton, such as wild cattle and horses,” noted Prof. Shai Meiri.

“Finally, in sites inhabited by modern humans, from about 50,000 to 10,000 years ago, approximately 70% of the bones belong to gazelles – an animal that weighs no more than 20-30 kg. Other remains found at these later sites came mostly from fallow deer (about 20%), as well as smaller animals such as hares and turtles.”

Procuring the same amount of food from smaller animals, however, required more effort and the development of new techniques and tools.

“While spears were sufficient for Homo erectus to kill elephants at close range, modern humans developed the bow and arrow to kill fast-running gazelles from a distance,” said Dr. Miki Ben-Dor.

The researchers also examined the possible correlation between the disappearance of different species and the evolution of climate in the region but found no tangible connection between the two phenomena.

“A widely accepted theory attributes the extinction of large species to climate changes through the ages,” Dembitzer noted. “To test this, we collected climatic and environmental data for the entire period, covering more than a dozen cycles of glacial and interglacial periods.”

The data included temperatures, rainfall and vegetation.

“A range of statistical analyses correlating between animal size and climate, precipitation and environment revealed that climate – and climate change – had little if any impact on animal extinction,” Dembitzer said.

The results of the study have far-reaching implications that go well beyond the scope of prehistoric southern Levant, the researchers pointed out.

“We believe that our model is relevant to human cultures everywhere,” said Barkai. “For the first time, we argue that the driving force behind the constant improvement in human technology is the continual decline in the size of game. Ultimately, it may well be that 10,000 years ago in the southern Levant, animals became too small or too rare to provide humans with sufficient food, and this could be related to the advent of agriculture.

“In addition, we confirmed the hypothesis that the extinction of large animals was caused by humans – who time and time again destroyed their own livelihood through over-hunting,” he remarked. “We may therefore conclude that humans have always ravaged their environment but were usually clever enough to find solutions for the problems they had created – from the bow and arrow to the agricultural revolution. The environment, however, always paid a devastating price.”