For more than 100 years, the inner secrets of the 30,000-year-old Venus of Willendorf remained an enigma. Clearly made from material not native to the area of lower Austria where it was found in 1908, archaeologists and researchers have been confounded by the origin of the voluptuous female figurine with its elaborately carved hairstyle, rounded belly and hips, and thin arms decorated with serrated arm rings resting on her full breasts.

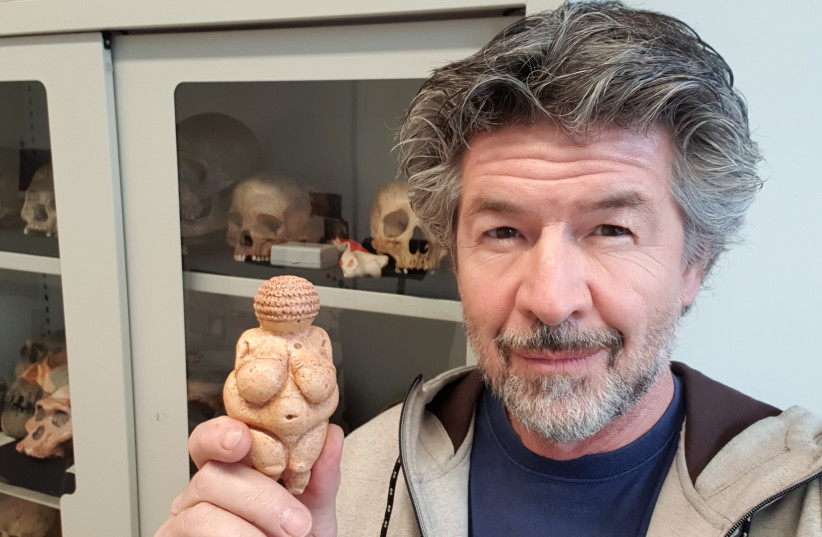

One of the most important examples of early art in Europe, the almost 11-cm. (4.3-inch) high figurine is made of “oolite” – a sedimentary rock formed from tiny spherical grains – which is not found in or around the village of Willendorf where it was discovered.

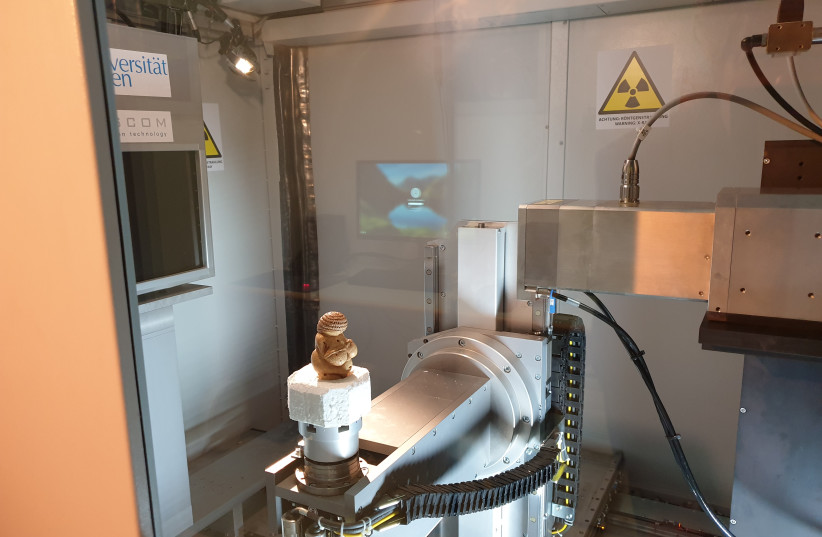

On display in the Natural History Museum in Vienna, the Willendorf Venus is considered a national treasure and has so far only been examined from the outside. Now, Weber’s team used a new micro-CT method similar to that used in the medical field to examine its interior. During several passes, the scientists obtained images with a resolution of up to 11.5 micrometers – a quality that is otherwise only seen under a microscope.

The multi-disciplinary research team led by anthropologist Gerhard Weber from the University of Vienna, geologists Alexander Lukeneder and Mathias Harzhauser, as well as prehistorian Walpurga Antl-Weiser from the Natural History Museum Vienna, determined that the material from which the Venus was carved likely comes from northern Italy near Lake Garda.

The result of their research was published in the February 28 issue of Scientific Reports.

Their findings shed new light on the remarkable mobility of the first modern humans south and north of the Alps during the Paleolithic era, said the researchers.

The first insight they gained was that the Venus does not look uniform at all on the inside, said Weber. They also discovered remnants of a tiny shell dated to the Jurassic period, and limonites, a larger, dense type of grain.

Rather than being smooth, the exterior of the figurine is porous with small cavities probably caused by the hard limonites breaking out when the Venus was being carved, explained Weber. The figurine’s navel appears to have been a fortuitous result of such a break.

Following the micro-CT analysis, the question still begging to be answered was clear: Where did the oolite stone from which the unique Venus was carved originate?

“This special [heterogeneous] property could be used to determine its origin,” Weber said.

“The Venus is one of the most important cultural artifacts in the world because of its unique form and style which is different from other Venus figurines,” added Weber. Most of the Venus figurines found have been made from bone, ivory or other types of stones, he added, but the Venus of Willendorf is the only one made of oolite stone.

“For more than 100 years, nothing much happened [in terms of learning about] the Venus. For a long time, legions of archaeologists have thought about her meaning, what it could be and why. You can have endless ideas, but you can never prove it. But we come from a different side. We come from evolutionary anthropology, about the evolution of humans. These are results from natural science that tell us something about these people.”

RESEARCHERS FIRST began the arduous job of analyzing and comparing the Venus oolite stone composition to that of oolite stone samples, both fresh from the field and those already excavated, from within a 200-km. (124-mile) radius, assuming this was the normal range for hunter-gatherer groups of that time. But when no match was found, they extended their search for some 730 kilometers (454 miles), to eventually include areas in France, Ukraine, Germany and Sicily.

Much to their surprise, the researchers found a statistically “strikingly close match” for the grain size distribution near Lake Garda in the Southern Alps of Italy. The researches checked and double-checked their results, and still came back up with the same findings. They were excited by the remarkable finding because it meant that the Venus, or at least its material, started a journey from south of the Alps to the Danube north of the Alps, suggesting that the first modern humans living in Europe were somehow in contact from Northern Italy and Lower Austria.

“This might indicate considerable mobility of the Gravettian people of that period and long-time transport of artifacts from south to north by modern human groups before the Last Glacial Maximum,” they said in their report.

“The interesting thing is how they got there, the mobility of people at that time and how far reaching their action radius was. We think they maybe possibly crossed the Alps, following the main Etsch, Inn and Danube rivers,” Weber added.

Another possible place for the origin of the rock is in eastern Ukraine, more than 1,600 km. (994 miles) linear distance from Willendorf, the researchers noted, though the samples are not as good a match as with those from Italy. Interestingly, similar but younger Venus figures were found in nearby southern Russia. The researchers noted that genetic results also show that people in Central and Eastern Europe were connected to one another at this time.

Noting that there have been only a few systematic studies dealing with human existence and mobility from this time in the Alpine region, Weber said he hoped their Venus study will help spark more interest in studies in this realm in cooperation with their new Vienna research network “Human Evolution and Archaeological Sciences,” which combines anthropology, archaeology and other disciplines to further clarify early history in the Alpine region.

One of the two possible migration routes from the south to the north would lead around the Alps and into the Pannonian Plain has already been suggested by other researchers. Weber’s team noted that another way to get from Lake Garda to Lower Austria would be via the Alps. Whether this was possible more than 30,000 years ago is unclear, they said, due to the climate deterioration that began at that time.

It may have taken years, and even generations for the group to travel from Northern Italy to Lower Austria, Weber said, all the time carrying the Venus figurine with them throughout the journey.

“It must have been of great significance or they would not have carried it with them for such a long time. They must have had important religious or spiritual ideas otherwise they would not have made this figure and bring it along with them for such a long time,” he said. “It wasn’t travel like today with GPS. They didn’t have suitcases. They had no understanding of where they were going. They were just following the rivers. They didn’t know they would end up in Willendorf. It took them generations to get there, and all that time they took this important object, this Venus, with them.”