The human desire to collect, and recycle items, to hold onto things from the past, is not as new as people would like to think, according to researchers from Tel Aviv University.

The study, led by PhD student Bar Efrati and Prof. Ran Barkai of the Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures, looked at what drove prehistoric humans to collect and recycle flint tools that had been made, used, and discarded by their predecessors.

An examination of a group of 49 flint tools at the 500,000-year-old prehistoric site of Revadim in the south of Israel’s Coastal plan revealed that many of them had been through two lifecyles, indicating that they had been recycled after their original user had tossed them away.

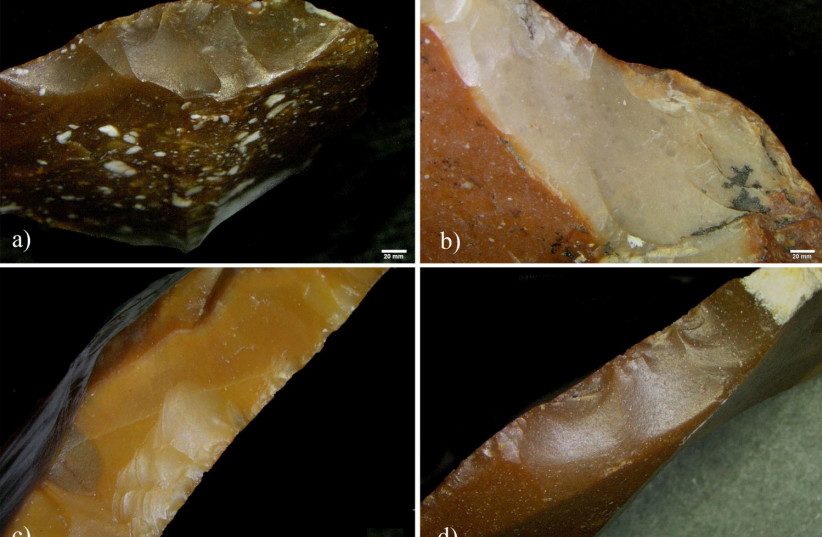

Researchers reached this conclusion by identifying two layers of patina— a chemical coating which forms on flint when it is exposed to the elements for a long period of time—on the tools, explained Efrati.

Their study, which was conducted in collaboration with Dr. Flavia Venditti from the University of Tubingen in Germany and Prof. Stella Nunziante Cesaro from the Sapienza University of Rome, Italy appears in the scientific journal Scientific Reports, published by Nature.

The making of flint tools requires the chipping away, or reduction, of the original piece of flint to create the desired tool, Efrati said, which also chips away at the patina. Because of two levels of patina detected on the flint tools they studied, it was apparent to them that the chipping away had been done in two different cycles.

Because the patina takes many years to form, they also know that the time between uses was significant but they can’t determine exactly how long the gap in use was, she said.

The theory that the second use of the tools came from a more spiritual, or emotional, reason is based on the way the second reduction was carried out, she said.

“The reduction which was done after the tool was collected was very minimal, and left most of the item whole,” she said. “We think it was left specifically and minimally modified to leave the item as it was.”

Minimizing the reductions required extra effort and thought to prevent from completely reducing the stone so it is not necessarily easier to minimize reduction and the act of recycling them was not done out of laziness, she said.

Instead, their study suggests that pre-historic humans had an emotional urge to collect old human-made artifacts, mostly as a means for preserving the memory of their ancestors and maintaining their connectedness with place and time.

"Based on our findings, we propose that prehistoric humans collected and recycled old tools because they attached significance to items made by their predecessors,” said Barkai. “Imagine a prehistoric human walking through the landscape 500,000 years ago, when an old stone tool catches his eye. The tool means something to him – it carries the memory of his ancestors or evokes a connection to a certain place.”

Efrati explained that stone tools with two lifecycles have been found at prehistoric sites all over the world, but the phenomenon has never been thoroughly investigated. In the current study, the researchers focused on a specific layer at Revadim - a large, open-air, multi-layered site in the south of Israel's Coastal Plain, dated to about 500,000 years ago. The rich findings at Revadim suggest that this was a popular spot in the prehistoric landscape, revisited over and over again by early humans drawn by an abundance of wildlife, including elephants. Moreover, the area is rich with good-quality flint, and most tools found at Revadim were in fact made of fresh flint.

The tools were shaped into a new active edge. Both edges, the old and the new were examined by the researchers under two kinds of microscopes, and via various chemical analyses, in search of use-wear marks and/or organic residues. In the case of 28 tools, use-wear marks were found on the old and/or new edges, and in 13 tools, organic residues were detected, evidence of contact with animal bones or fat.

They determined that interestingly, the tools had been used for very different purposes in their two lifecycles - the older edges primarily for cutting, and the newer edges for scraping and processing soft materials like leather and bone.

“These items were not related to people they knew or remembered but it was a connection to a person in the past,” said Efrati. “Like today sometimes we pick up certain objects and it reminds us of something and it is comforting for us to collect and have it.”

Prehistoric humans were intelligent beings, she said, and not “primitive” as they are often depicted.

“They were smart like us and even more than us. They knew their surroundings and how to survive in it better than we do now with all our technology,” she said. “This shows us that collecting is not a new invention to modern time. It is something rooted in us in more ways than we can even think.”