Almost exactly 255 years ago, on the 10th day of the Jewish month of Adar I in the year 1767, 14-year-old Luna bat Yehuda Ambron finished her task and put down her quill.

She had completed scribing the whole Scroll of Esther with its accompanying blessing scroll. As had become common practice in those days, with the advent of the printing press and books, she also wrote an inscription in tiny script below the liturgical text at the bottom of the parchment.

“With the help of G-d, the writing of these blessings with the scroll was completed on 10th Adar I 1767... [by] the modest and pleasant girl Luna, daughter of the honorable and wealthy Yehuda Ambron, in the 14th year of her life... May we merit to see miracles and wonders speedily in our times,” she wrote, forming the letters of her name just a little bit bigger than the rest.

The secular date was March 1, 1767.

Little is known about the teenager other than that she belonged to a prominent wealthy Jewish family in Rome, who had come to Italy just before and after the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492. Her father owned several businesses, including a successful furniture-making business that also produced pieces for the Catholic Church and ecclesiastical use. Luna married Ya’acov David ben Mordechai Di Segni 10 years after finishing the scroll, and they moved to the port city of Livorno on the west coast of Tuscany, where they helped expand her father’s business.

As for the history of the beautifully illustrated manuscript she wrote, all that is known is that it was held in private collections until it surfaced at an auction by the Jerusalem Kedem Auction House last December. With stiff competition from private collectors, it is nothing short of a miracle that the Israel Museum in Jerusalem was able to acquire the scroll from an Italian Jewish family with generous funding from the Mandel Foundation, making it available for public viewing for the first time.

“The prices of Judaica and illustrated manuscripts are very high, and it is hard to compete with private collectors, though it is important that these objects stay in public collections,” Dr. Rachel Sarfati, chief curator of the museum’s Wing for Jewish Art and Life, said at a press viewing prior to restoration and research of the scroll by Anna Nizza-Caplan, the museum’s curator of Hebrew manuscripts.

One of her reasons for making such a manuscript available to the public was to highlight the complete story of the history of the Jewish people, Sarfati said.

“It is important to see the whole picture of the Jewish world and to tell about the role of women in the religious life of their communities,” she said. “It is very important to also show a different part of us.”

Before such a purchase is made, its authenticity and provenance must be confirmed, she added.

Nizza-Caplan said: “Nobody has done research on this scroll. It could have been purchased by a private family again, and we wouldn’t have known. Now it is our job to investigate; sometimes we do find information. On the other hand, we know we are at a starting point with a lot of research to do.”

It can be assumed that Luna came from a family that valued education for their children, including their daughter, she said.

The curators hope the scroll will be available for public viewing by the High Holy Days.

ACCORDING TO the Talmud, the Scroll of Esther, or Megillat Esther, is the only scroll women are permitted to scribe because the name of God is not mentioned in it, Sarfati said.

It also is usually the scroll with which young male scribes began practicing their hand for the same reason, she said. While some young male scribal apprentices might have begun their training at the young age of 14 or 15, it is still rather a young age to complete a scroll, and that this scroll was scribed by a young woman makes it even more exceptional, she added.

It is only recently that a handful of women have begun to write Torah scrolls, although they have been declared invalid by Orthodox rabbis.

While it is considered acceptable to read from a Scroll of Esther written by a woman, the Talmud maintains that it should only be done if there is no scroll written by a man available.

“So you can understand why this Esther Scroll is so unique for us and our collection,” Sarfati said. “This is an unusual example of what women are allowed to do until this day.”

Israel Museum director Denis Weil said the new acquisition is part of the museum’s mission to “represent and showcase” all members of Israeli society, including a “14-year-old girl no one knows about.”

The large Megillat Esther is written in Sephardi-Italian script – influenced by the new printed script of the period – on two parchment membranes, with the first membrane including a decorative right edge. The first column is preceded by a large colorful floral illustration, and the initial word Vayehi is written in large, ornamental letters. The scroll is mounted on a wooden roller with a tiered finial, common in Italian megillot of that time.

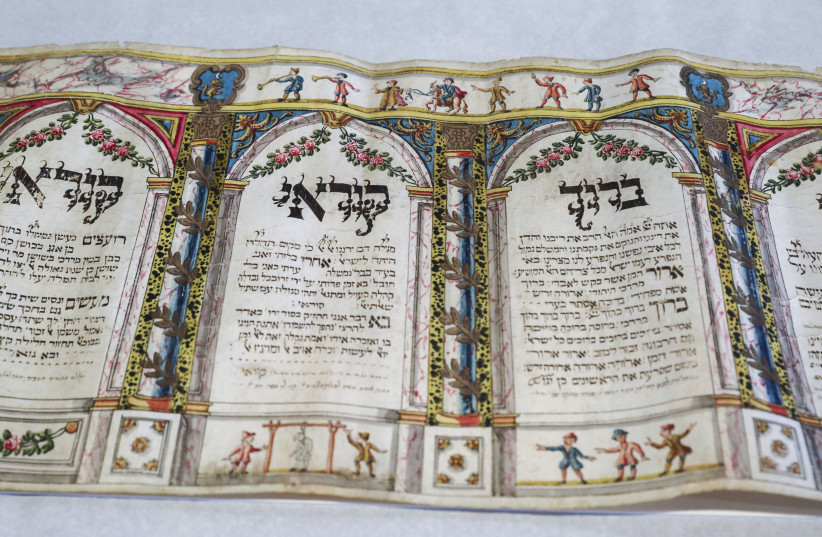

The blessing scroll parchment is elaborately decorated, and the text is divided into four columns, including the two blessings for the megillah reading and the liturgical poem Korei Megillah by Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra.

The initial words of the blessings and poem are inscribed in large, ornamental letters. The text is set in an architectural frame comprised of four marble arches decorated with branches and flowers that rest on five stylized marble pillars. Above the arches is an illustration depicting Haman leading Mordechai on a horse, preceded by two trumpet-blowing figures and followed by four additional figures.

Two other illustrations appear at the foot of the leaf: one depicting Haman hanging on a pole flanked by two figures, and a second depicting three other figures. On either side of the upper illustration are two emblems featuring a lion and crescent – the coat of arms of the Ambron family – against a blue background.

JEWISH FAMILIES during this period assumed the custom of a family coat of arms, and many can also be seen in ketubot, Jewish marriage contracts, Nizza-Caplan said.

The name of the illustrator is unknown, as they were not considered important in the scribing of Jewish manuscripts, Sarfati said. What was important was the holy text, she said.

Only two other Scrolls of Esther are known to have been written by women, both originating in Italy and in private collections. One, copied by Stellina bat Menachem ben Jekutiel of Venice, is thought to be the earliest fully decorated megillah in existence. It is part of the Swiss Braginsky Collection, considered to be the largest private collection of Hebrew illustrated manuscripts, parts of which have been loaned to museums and can be viewed on the collection’s website.

A handful of examples of medieval female scribes are known, but Stellina’s scroll is the only early modern example of a scroll copied by a woman. The second Scroll of Esther was written by Camilla bat Moshe Efraim in 1770.

“One can say, ‘Who cares what happened 250 years ago,’ but in this case, it is something so outstanding it is relevant and important to know that it happened – how in Italy there was an approach to women that in a way that gave them more space in some circumstances,” Nizza-Caplan said. “I don’t know the circumstances of [Luna’s] signing the scroll, but it was something that was deliberate. What remains for us now is that she did write her name to take credit for her work, and she is still alive for us, and that is very important.”