Once considered the official cultural and economic capital of the Roman Empire in Asia Minor, the southern Aegean Sea port city of Ephesus, located today in Turkey, was also home to one of the ancient world’s largest and most impressive libraries that housed over 12,000 scrolls and manuscripts, some tucked away in niches along the inner wall.

Julius Aquilas, son of Roman senator and Roman Legion Commander Celsus Polemeanus, began construction of the Celsus Library – the third-largest library in the Roman world – in honor of his father around 110 CE, completing it in 135. Celsus is buried in a sarcophagus beneath the main entrance of the library.

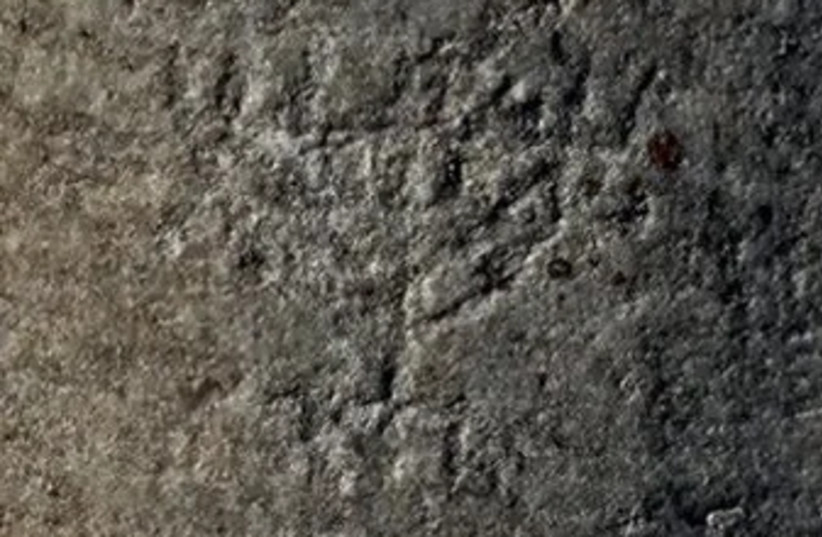

Somewhere along the ancient history of the library, someone carved a graffiti image of a menorah into one of the steps of the library’s marble staircase. The history of the menorah can be nothing more than conjecture, noted Dr. Avner Ecker of the Martin (Szusz) Department of Land of Israel Studies and Archaeology at Bar-Ilan University.

Still, he said, since it is located in a very central spot – adjacent to the Agora of Ephesus – the image of the menorah is not meaningless.

In a 1980 companion article to his book Fishers of Men: The Way of The Apostle tracing the path of Paul the Apostle – coauthored by photographer Gordon Converse and archaeologist Robert J. Bull – American Near East scholar and lecturer B. Cobbey Crisler describes their discovery of the menorah based on his memory of having seen the menorah seven years earlier during excavations being conducted by Austrian archaeologists.

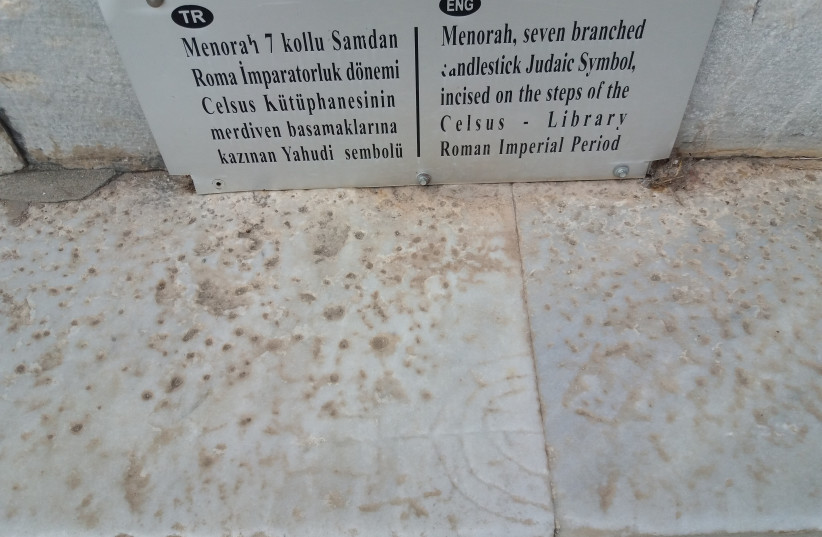

A plaque has been put up next to the menorah, but it can be easily missed if one is not walking up the stairs in just the right place.

No written sources mention the Celsus Library, said Ecker, and all information about the library is from a dedication inscription uncovered at the site. The first level of the library had statues of the virtues of Celsus in niches, and on the second level, there were statues of Celsus and his family.

The library and its contents were destroyed in a fire in 262 CE either by an earthquake or an invasion by the Goths, and an earthquake in the 10th or 11th century destroyed what remained of the façade. German and Austrian archaeologists began excavating the site in 1895 under the direction of Otto Benndorf and Carl Humann. Excavations at the site have continued since then through the Austrian Archaeological Institute, which Benndorf established. The institute reconstructed the Celsus Library in the 1970s.

Many of the finds from the Ephesus excavations have been taken to museums around the world, including the British Museum in London and the Ephesus Museum in Vienna, where the original statues of virtue are now located.

“Celsus’s family was very important,” Ecker said. “He was a senator in Rome, and as commander of a Roman legion may have had some involvement in Syria and even in the Jewish Revolt. So one theory holds that the menorah graffiti may have been some sort of response to that. But then the person who did that would have needed to have some specific knowledge about his career.”

Another theory holds that because of the vast numbers of manuscripts kept at the library, it is very likely that some of those included Jewish manuscripts, and the carving of the menorah was someone’s way of indicating that the library also had some Jewish content, he said.

Yet another possibility is the stone with the menorah carving had simply been repurposed from another site during renovations on the library stairs.

“But then that would take away from the romance surrounding the story of the menorah,” he admitted.

And maybe someone just wanted to make his mark similar to modern-day graffiti, said Eckert, noting that graffiti was more tolerated in ancient times.

“It would have taken a matter of minutes to make if you have the skill and right tools,” said Ecker. “You would have had to have a hammer and chisel to do that, a nail would not have been enough.”

The menorah became employed as a Jewish symbol sometime in the third century, he said, probably at the same time the cross became a common symbol for Christianity, as a reaction to Jews wanting to express their separate identity. There are few examples of menorahs being used as random graffiti, he said, and Ephesus is one of them. Another example can be found carved on the Roman road outside of Cyrenaica in modern-day Libya, from the second century, thought to be a symbol of the Diaspora Revolt by Jewish rebels in 115-117 CE, which had its hub in Cyrenaica.

In excavations in Ephesus by Austrian archaeologists at the beginning of the 20th century, the Celsus Library menorah was discovered under a fountain from around 400 CE, so though the exact date for the menorah graffiti is not known, it was carved likely at the end of the second century or early third century CE, Ecker said.

LOCAL TURKISH tour guide Hasan Gulday, who has worked with Israeli and Jewish tourists and writes on his website about the menorahs in Ephesus, also points out that another menorah graffiti was etched next to the so-called brothel building in Ephesus. The most important carving of a menorah in Ephesus, however, is under the Mezeus and Mithradates Gate, built by two Persian Jewish freed slaves, and dedicated to the Roman emperor who had been their former master, Gulday said.

After the destruction of the First Temple, a large number of Jews moved to Western Turkey, he said, in a large wave of Roman and Hellenistic colonization.

“Jews were considered important for business and trade due to their high literacy rate at a time when only 3% of the general population was literate,” said Gulday.

According to the Roman census, 10% of the population of Ephesus was Jewish, and they later had the right to collect taxes for the rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem, which was very unusual, he said. Large Jewish populations also existed in nearby Hierapolis and Sardis, where there are impressive remains of the largest Western synagogue. Today, many of the Jewish residents of the city of Izmir, ancient Smyrna, are descendants of the original Jewish inhabitants of Ephesus, Gulday said.

A cosmopolitan city, ancient Ephesus had an established and flourishing Jewish community whose presence was documented from the first century BCE by Josephus, among others, noted Ecker. The Jews of Ephesus, who were Roman citizens, were exempt from military service, and had the right to have someone take care of their dietary needs in the market assuring them which products were kosher, said Ecker.

“That was a huge privilege,” he said.

Ephesus was also an important place for Christians, where two of Jesus’s apostles, Paul and John, spent time preaching to the local Jewish and gentile community. John mentions Ephesus in the Book of Revelation as one of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor. The apostle John held the position of bishop of Ephesus.

The second-century Christian text “Dialogue with Trypho” between early Christian writer Justin Martyr, originally from Shechem (Nablus), and Trypho, thought to be a Jewish refugee from the Bar-Kochba revolt, also took place in Ephesus, noted Ecker.

There was a large synagogue in Ephesus near the Celsus Library, but it has not yet been found.

This month marks both US National Library Week and National Librarian Day.