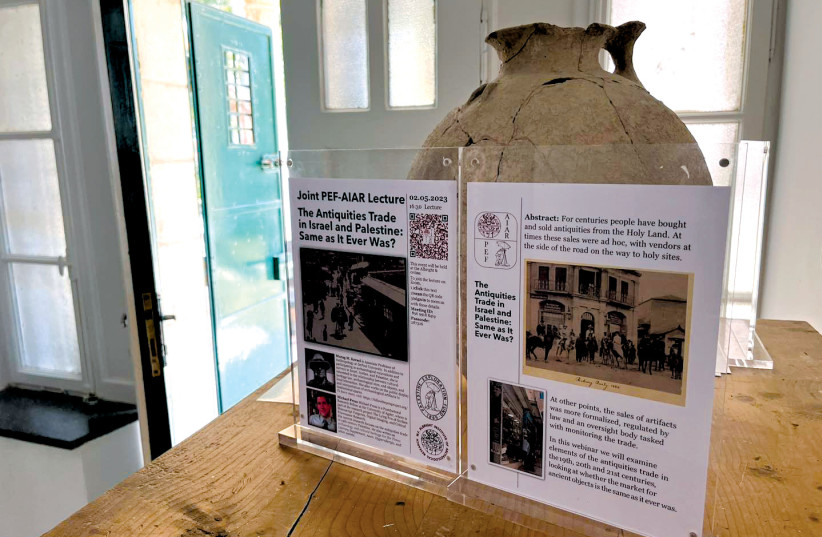

Israel’s central – and arguably shameful – role in the global antiquities business was the subject of a Zoom lecture on May 2 sponsored by the W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem and the Palestine Exploration Fund headquartered in London.

Titled “The Antiquities Trade in Israel and Palestine: Same as It Ever Was?”, the joint presentation featured Michael Press, a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of Agder in Kristiansand, Norway, specializing in the archaeology of ancient Israel; and Morag Kersel, an associate professor of anthropology at DePaul University in Chicago, Illinois, who studies the relationship between cultural heritage law, archaeological sites and objects, and local interaction.

Press offered a scholarly overview of how the trade in antiquities burgeoned in the 19th century as tourism and Holy Land pilgrimage reached a mass scale, while Kersel spoke about how the quasi-licit trade functions today.

The Ottoman Empire enacted its first antiquities law in 1869 prohibiting the export of the empire’s patrimony, Press noted. However, the first English-language Baedeker guide to Palestine and Syria, published seven years later, detailed the sum of baksheesh – a paltry few francs – needed to grease the palm of a Turkish customs officer to smuggle out a centuries-old souvenir.

The discovery in 1868 in Dhiban, Jordan, of a monumental Iron Age inscription mentioning King Mesha of Moab triggered an explosion of forgeries, continued Press. Notably, in 1873 Jerusalem antiquities dealer Moses Wilhelm Shapira (1830-1884) hoodwinked Germany into purchasing a trove of 1,800 fakes, he said.

Most pilgrims were interested in acquiring objets de piété. A popular article was the widow’s mite, the least valuable coin circulating in Roman Judea, which Jesus mentioned in Mark 12:41–44 and Luke 21:1–4. The market in ancient currency included a brisk trade in forged gold and silver coins. Some pilgrims carried with them valuable numismatic items from Europe, which they sold in Palestine to fund their journey.

The quickly evolving trade included Samaritan, Hebrew and Greek manuscripts, gems and seals, and ancient lachrymatories – perfume vials that widows would ostensibly fill with their tears and place in tombs as symbols of mourning for their deceased loved ones.

Press showed advertising from an American newspaper for the Phoenician, i.e., Roman glassware of Azeez Khayat (1875–1943). Born in Tyre, Lebanon (then part of Ottoman Syria), Khayat arrived at Ellis Island in 1893 and became a United States citizen five years later. Using the small collection of ancient glass he had brought with him, he became a dealer on Rector Street in Manhattan’s Little Syria. On repeated trips to his Middle East homeland, he was able to bring back thousands of artifacts – often excavated by his own workmen – and sell them in a gallery he opened first on West 11th Street and later at 366 Fifth Avenue, opposite the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. Many notable US museums acquired important objects through him.

Finally, Press concluded, the insatiable market for Holy Land antiquities – both counterfeit and real – included pottery vessels and oil lamps.

Bringing the story to the present, Kersel spoke about the trade today.

What are Israel's laws on trading antiquities?

Technically, the restrictions imposed by Israel’s Antiquities Law of 1978 forbid the sale of any man-made item from before 1700 CE. However, the act grandfathered the sale of items already in the inventory of the country’s 50 or so licensed antiquities dealers. Since those catalogs are often nondescript and include unclear photographs, and since the lists are rarely updated when an item is sold, there is considerable opportunity to introduce newly and illegally acquired items, Kersel explained.

Underfunded and overstretched, the Israel Antiquities Authority’s anti-theft unit does its best to monitor the dealers’ illegal activities. Most shops are located along the Via Dolorosa in the Old City of Jerusalem and resemble Aladdin’s cave of treasures. The shops in luxury hotels are decked out with elaborate vitrines resembling prestigious museums. All provide a certificate of authenticity cum export permit with each sale, she noted.

Typical is Zak’s Antiquities run by Zak Mishriky, located in the Old City’s Christian Quarter Road, which advertises: “Invest in Biblical Antiquities. Ageless, timeless & priceless.” Fine print about the source of the merchandise notes: “The majority of our ancient artifacts come to us through private collections and auctions here in Israel.”

Kersel the archaeologist has devoted two decades to tracking how the illicit trade in unprovenanced objects extends from the ground to the consumer. In a network that extends from the UAE through Jordan, the West Bank and Israel to the UK and the US, shady Arabs and Israelis, she noted, are pillaging the Middle East’s cultural artifacts. Their criminal enterprise results in the destruction of archaeological sites, the desecration of ancient graves, and theft from museums. Moreover, it compromises the understanding of the past. Some tie the business to funding terrorism.

She categorized those buying these items into four groups.

The first she called explorers – impecunious individuals, some of whom volunteer on archaeological excavations, who generally purchase low-cost items from a cabinet of curiosities in the Old City and do so in search of an authentic exotic cultural experience.

While not condoning their behavior, Kersel excoriated the second group – the well-heeled elite. She was particularly critical of billionaire Steve Green of Oklahoma. The evangelical Christian, whose family owns the Hobby Lobby craft store chain, used his fortune to establish the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., which opened in 2017.

“There were a lot of red flags,” she said of the MotB’s acquisitions. All 16 Dead Sea Scroll fragments Green purchased proved to be forgeries, she noted. Kersel explained how the avaricious antiquities enthusiast’s agents mislabeled the thousands of artifacts he purchased. Shipping them in small batches to various American addresses, they hoped to stay below the radar. The scam was finally stopped thanks to a tip-off from a FedEx agent, she added. Some 3,450 items were seized by the US authorities.

Kersel was similarly harsh in discussing disgraced Wall Street financier Michael Steinhardt, who during a period of high inflation in the 1970s conceived that antiquities are a commodity likely to appreciate quickly. Like Green, Steinhardt sought to gain validation for his purchases – including a priceless group of Neolithic masks perhaps looted from caves by the Dead Sea – by donating them to museums. Steinhardt was a major benefactor of the Israel Museum.

Kersel identified the third group as religious tourists. Like their 19th-century forebears, they too are interested in small-scale items like the widow’s mite or lachrymatories.

The fourth group she identified are members of a charter – i.e., alumni of a university or members of a sports or social club on an organized tour, who are driven by group psychology. If one person buys an artifact, that leads their peers to do so as well, he said. And those items must be “cheap, portable and dustable.”

Citing Nelson H. H. Graburn, a professor emeritus in sociocultural anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley, Kersel said that such charter tourists will knowingly purchase a replica in order not to lose face with their fellow travelers.

“Afghanistan’s Law on the Protection of Historical and Cultural Properties (2004) strictly regulates the excavation and sale of antiquities: allowing private ownership of only registered antiquities and prohibiting export except by the state,” said Press. The result has been to drive the business underground.

Would the result be any different were Israel to simply declare the antiquities trade illegal, revoke the dealers’ licenses, and nationalize their inventories?

Kersel cautioned that such a radical solution would not end the trade. In an e-mail, she wrote: “I don’t think that the demand for biblical antiquities will ever end. Everyone wants something from the Holy Land, but I do think we can create better collectors, who only buy from licensed dealers and who ask about provenance/the origin stories of the piece.” ■