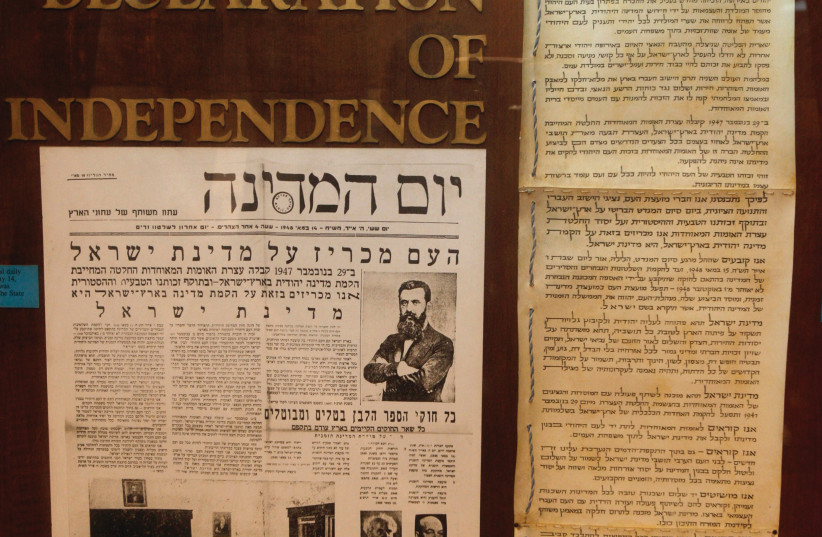

Israel’s Declaration of Independence has taken central stage this year in the country’s divided politics — sometimes literally, as when Israelis opposed to proposed changes to the judiciary carried a massive version in their protests.

Now, the Declaration of Independence is also the subject of a new podcast from the producers of Israel Story, which its creators say is the most listened-to Jewish podcast in the world.

“Signed, Sealed, Delivered?” is a deep dive into Israel’s founding document, called Megillat Haatzmaut in Hebrew. It was conceived before the judicial overhaul proposal as a way to capture the sweep of Israel’s history in advance of its 75th birthday, creator and host Mishy Harman told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Harman said he was interested to learn more about the 37 signatories to the declaration, which plays a quasi-constitutional role in Israeli law, and their descendants.

“It’s sort of like a pointillist painting. When you look at them from afar, you think, well, it’s a pretty monolithic group,” Harman told JTA. “Then when you delve in you see that actually, it was a very diverse group. … I wondered whether, in the 75 years since the signatories put their name on the Megillat Haatzmaut, that diversity had expanded or shrunk.”

The podcast’s original, Hebrew-language incarnation was inspired by NPR’s “This American Life” and weaves together quirky personal anecdotes, interviews and soundscapes to tell the story of Israel beyond the headlines. In 2014, Harman launched a sister podcast in English, now produced in partnership with The Times of Israel and The Jerusalem Foundation.

From a Palestinian-Brooklynite on a hunt for a wife in the Tulkarem Refugee Camp to an Orthodox matchmaker whose dates take place just outside her apartment, the stories featured on the podcast shed light on questions of culture, identity, history and — despite Harman’s avowed efforts — politics.

A decade later, Israel Story has several hundreds of thousands of listeners from more than 190 countries around the world, 60% of whom live in North America, according to the podcast’s analysis. Around 50% of listeners are not Jewish.

Harman recently spoke with JTA about the new podcast, how he threaded the politics needle and what surprised him most about how the descendants of the 1948 signatories had to say.

The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

JTA: What’s the most surprising piece of feedback you’ve received from listeners?

There are stories that we work on for many months and that are very alive in our own lives, but then they come out into the world and we never really know in what ways they’re going to impact listeners. From time to time, we hear from people who tell us that as a result of hearing an episode — an outcome of our storytelling and craft — they adopted a child with Down Syndrome or moved to Israel or decided to come out as trans. It’s a cool thing to realize that stories have an impact and that they really change people’s lives.

JTA: Were you always a storyteller?

I think we’re all storytellers in some very fundamental way. I spent a lot of a lot of time in academia, I have a Ph.D. in history, and I always thought of history as a form of storytelling. And all of my years in universities, the things that stayed with me were stories rather than academic arguments. I think most of us experience life by telling stories.

Would you say your identity as a Jerusalem native informs your storytelling?

It definitely does in a very clear, clear way. Jerusalemites have a tremendous advantage in that they wake up every morning into a reality which is complicated and is full of people trying to negotiate their various different narratives and coexist and live side by side. You walk in the streets and within a few steps you see people whose lifestyles and belief systems are very different from yours. You see somebody and you take in what they have or don’t have on their head, or what color skin they have, or what clothes they’re wearing, and immediately, put a label on them and within a second, you’ve constructed a whole sort of narrative about who that person is, who they vote for, what their Shabbat table looks like, what they did or didn’t do in the army, what they think about the gay pride parade and whether they go to demonstrations about the judicial reform or not. It obviates the need to actually listen and ask them what their story is.

By removing that visual element, we allow listeners the gift of being able to suspend their judgments for a little bit and listen — really listen — to the story of somebody who they wouldn’t otherwise talk to or meet in the real world, allowing people to train their muscles of empathy. Which I think is a good thing in our society in general.

I’d love to talk about your new series called “Signed, Sealed and Delivered,” marking Israel’s 75th anniversary. How did it come to be?

We set out to tell these complicated, nuanced details of Israel in a way that has nothing to do — and we’re very intentional about this — with hasbara [public diplomacy]. We’re not interested in having people like Israel or support Israel. We’re Israelis, we live here, we find our society to be interesting and we want to tell stories to hopefully make other people also interested in Israel. What they think about Israel is their own business, obviously. And as such, we’ve resisted many, many offers by various different official sources of funding. We also tell stories in which Israel doesn’t look so good.

Back in September, so before the last round of elections and definitely before the judicial reform and the demonstrations, we had this idea to go back to Megillat Haatzmaut, which of course has since become sort of a rallying call of the demonstrations, and see the way in which the founders of the state envisioned Israel and how Israel has fared in various different ways. We’re an apolitical organization. We try to shy away from overtly political content, which is always a tricky question, because obviously, the follow-up question is, what is political content?

A story of someone buying a hat in Israel is political …

I completely agree. But we weren’t interested in being another voice in this sort of cacophony of voices about Israeli politics. I was reading Megillat Haatzmaut again and then I went down to the signatures and started reading up about them. I was interested to see who these people were, and what became of them. Because the interesting thing about this group of 37 men and women who signed the Megillah is that even though there were no non-Jews — and let’s just put that on the table because it’s an important fact to state — it’s sort of like a pointillist painting. So when you look at them from afar, you think, well, it’s a pretty monolithic group of Russian and Polish Mapainikim [members of the Mapai political party, a democratic socialist party helmed by then-Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion that was a precursor to the present-day Labor Party]. And then when you delve in you see that actually, it was a very diverse group. There were revisionists, communists, haredim, atheists, young and old, Mizrahim and Ashkenazim — in skewed numbers — and men and women, again, obviously, in skewed numbers.

I wondered whether, in the 75 years since the signatories put their name on the Megillat Haatzmaut, that diversity had expanded or shrunk.

Out of the 37 signatories, 14 still have children who are alive, and the rest have grandchildren or nieces and nephews and stuff like that. We set out to locate the closest living relatives of each one of the signatories and interview them, both about their ancestors and also about the promise of the Megillah, the ways in which we lived up to that promise, the ways in which we didn’t live up to that promise.

We tried to have each episode address a different facet of Israeli society. We also have a bunch of bonus episodes, including one about the word “God” which famously doesn’t appear explicitly in the Megillah, and one about the word “democracy,” which also famously doesn’t appear.

Was there anything you learned that you didn’t expect?

Yes. Obviously every interview has its own surprises. For example, in the episode about Sa’adia Kobashi, who was the lone Yemenite signatory of the Megillat Haatzmaut, we interviewed his son, Avinoam Kobashi, who is himself 91 years old and from a very, very traditional background. Yet when we spoke to him, his main critique of Israel today was the lack of religious pluralism at the Western Wall and the fact that women can’t pray [with a Torah scroll] there, which is a surprising thing and not exactly what you would imagine he’d say.

I would say as a whole, looking at the entire project, what was surprising to me is that while we do have a very wide range of opinions — from descendants who talk about Israel as a Judeo-Nazi state or like Ben Gurion’s grandson who talks about Israel as an apartheid state, all the way to descendants who say that democracy isn’t a Jewish value and not something that we should aspire to — I expected there to be a pretty even distribution among the descendants in terms of their positioning within Israeli society, and to my surprise, I would say that the vast majority, the bulk of the people that we talk to, are squarely within the center-left camp.

They are definitely horrified by the judicial reform and many of them are very active in the protests. I found that surprising. We had very, very few Bibistim [Netanyahu supporters] which is surprising given the fact that the Likud is the most popular party in Israel. There were people who are much more right-wing than Bibi, but as a whole, the group tended to lament the fact that we are not living up to the notions of equality, irrespective of race and ethnicity and gender, that were stipulated in Megillat Haatzmaut.