When the large animals consumed by prehistoric humans went extinct, people had to develop better weapons for hunting smaller prey, thereby driving evolutionary adaptations, according to a recent study from the archaeology department of Tel Aviv University (TAU).

The study, led by Dr. Miki Ben-Dor and Prof. Ran Barkai, was published in the journal Quaternary under the title “The Evolution of Paleolithic Hunting Weapons: A Response to Declining Prey Size.”

The study was designed to examine a broader unifying hypothesis that the team proposed two years ago: that the cultural and physiological evolution of prehistoric humans – including increased cognitive abilities – evolved as an adaptational response to the need to hunt progressively smaller and quicker prey.

Five selected case studies in Africa and Europe were analyzed to test this, focusing on the relative presence of megaherbivores (larger than 1,000 kg.) in the transition between the Acheulean/Early Stone Age and the Middle Paleolithic/Middle Stone Age.

“We analyzed findings from nine prehistoric sites – in South Africa, East Africa, Spain, and France, inhabited during the transition from the Lower to the Middle Stone Age (Paleolithic), about 300,000 years ago, when Neanderthals and homo Sapiens first emerged,” said Ben-Dor. “The bones [found at archaeological sites] reflect the relative quantities of different species hunted by humans, such as elephants, fallow deer, and so on.”

The prey, and the tools used to hunt them, changed over time

The researchers looked for a correlation between the arrival of stone-tipped spears, and the progressive decline in prey size. “Specifically, we examined the emergence of a sophisticated stone-knapping method known as the Levallois technique, which is especially indicative of cognitive development: unlike earlier knapping methods, here the craftsman first prepares a core of good-quality stone, then cuts a pointed item off with one stroke – a process that requires the individual to imagine the final outcome in advance. We found that in all cases, at all sites, stone tips made with the Levallois technology appeared simultaneously with a relative decrease in the quantity of bones of large prey.”

Ben-Dor added that “studies of contemporary hunter-gatherers indicate that a wooden spear is quite sufficient for hunting large prey like an elephant. The hunters first limited the animal’s mobility – for example by driving it into a swamp or digging a trapping pit and concealing it with branches – and then thrust the spear into the prey and waited for it to bleed out.

On the other hand, Ben-Dor continued, “a middle-sized animal like a deer is much more difficult to trap, and [even if it could be hit with] a wooden spear, it would probably run away. A more substantial wound from a stone-tipped spear is likely to slow it down and reduce the distance it can run before ultimately collapsing – increasing the hunter’s chances of retrieving the fallen prey. This insight further elucidates our findings from hundreds of thousands of years ago, when stone-tipped spears were developed in response to the increasing scarcity of large prey.”

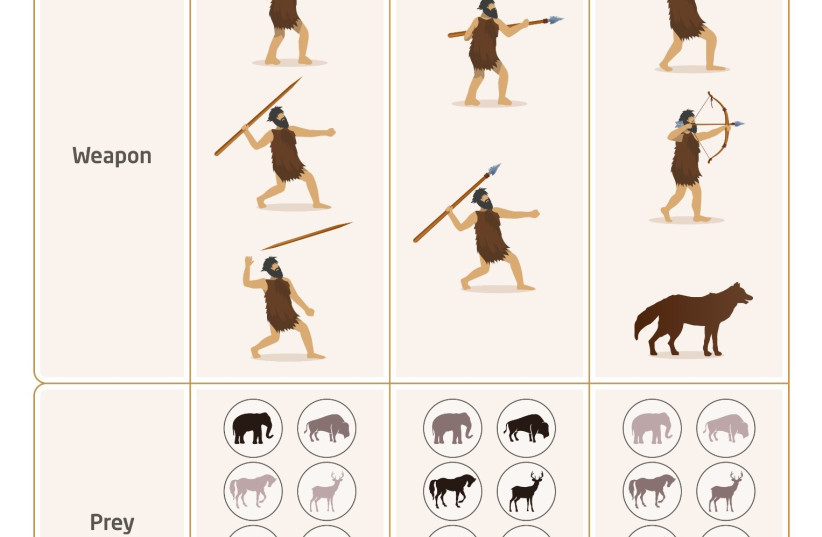

The researchers explained that hominins “began to make stone tools about three million years ago and started to hunt some two million years ago, with hunting weapons evolving constantly throughout prehistoric times. Homo erectus, the ancestor of all later types of humans, used a wooden spear, probably thrusting it into large prey from up close. Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, which emerged about 300,000 years ago, upgraded their spears by adding stone tips that they produced with the more-sophisticated Levallois technique. These stone-tipped spears were apparently used for both thrusting and hurling,” Ben-Dor continued.

About 50,000 years ago, more complex hunting systems like the bow-and-arrow and spear thrower began to be used regularly by Homo sapiens. At the end of the Upper Paleolithic about 25,000 years ago, new hunting techniques emerged, such as dogs, traps, and fishing hooks. This continual evolution of hunting weapons, necessarily accompanied by improvement in human cognition and skills, has been known for a long time, yet a unifying hypothesis explaining all of this, or linking these adaptations to an environmental change, was not proposed. According to Ben-Dor, this is the challenge that their research aimed to address.

Barkai noted that for the past decade, “we have been searching for a unified explanation for focal phenomena in the cultural and biological evolution of prehistoric humans. Our excavations at the Qesem Cave site [on the western slopes of the Judean Hills near the city of Rosh Ha’ayin] led us to conclude that elephants, a major component of the human diet in our region for a million years, disappeared about 300,000 years ago as a result of overhunting and climate change.”

With the huge elephants gone, humans had to find ways for obtaining the same number of calories from a larger number of smaller animals. In short, Barkai said, the hypothesis was that “at the beginning, the largest animals were hunted, and when these were gone, humans went on to the next in size, and so on. Finally, when hunting was no longer energetically viable, humans began to domesticate animals and plants. That’s how the agricultural revolution began.” These changes can explain the factors that drove the physiological and cultural evolution of Paleolithic humans, including the improvement of cognitive capabilities.

The new findings corroborate this hypothesis, following another study which they published last year, together with TAU zoologists Jacob Dambitzer and Prof. Shai Meiri. Surveying data from archaeological sites dating from 1,500,000 to 20,000 years ago, the 2022 study found that the dominant species of prey at the beginning of the period was a 12-ton elephant, and at the end it was a 25 kg. gazelle. In addition, the data indicate that the average weight of animals hunted by humans a million years ago was three tons, going down to 50 kg. 20,000 years ago. In other words, prey size decreased continually through time.

“We propose for the first time an explanation for one of the most intriguing questions in prehistoric archaeology – why did tools change?” said Barkai.

The usual explanation is that tools changed due to improvements in the cognitive abilities of humans. But, according to Barkai, this begs a subsequent question, which is: Why did humans become smarter all of a sudden? What was the advantage of having a large brain that consumes so much energy?

“We showed that these biological and cognitive changes correlate directly with the size of prey,” Barkai said. “To hunt small elusive animals. Humans had to become smarter, faster, more focused, more observant, and more collaborative. They had to develop new weapons for hunting from afar and learn how to track their prey. They had to choose their prey carefully, with preference for high fat content, to ensure a sufficient energetic return, because hunting a large number of agile gazelles requires a much higher investment of energy than hunting one giant elephant. This, we propose, is the evolutionary pressure that generated the improvement in human ability and tools.”