According to the Bible, the “United Kingdom of Israel” existed from the 11th century BCE and was ruled by Saul, David, and David’s son Solomon. But the united kingdom divided into two – Israel and Judea – about 975 BCE after King Solomon died and it was taken over by his son, Rehoboam – his anointed successor who ruled over the Southern Kingdom comprised of territory belonging to the tribes of Judah and Benjamin. The schism occurred when Jews rebelled against heavy taxes that were charged by the monarchy.

Israel consisted of Samaria and the Shechem in the North, while Judah and Jerusalem served as a center of religious significance in the South.

Until now, there has been only biblical and historical evidence but no indisputable archaeological remains to prove the exact chronology.

The formation of the Kingdom of Judah has been a subject of heavy debate among scholars, with a dispute emerging between biblical minimalists and biblical maximalists on this particular topic. Due to geopolitical factors like security issues, isolation and political changes, the core area of the Kingdom of Judah on the south-central highlands has seen limited archaeological exploration compared to regions west of the Jordan River.

Some scholars had suggested that Jerusalem, the kingdom’s capital, did not emerge as a significant administrative center until the end of the 8th century BCE. Before then, the archaeological evidence suggests its population was too small to sustain a viable kingdom.

Now, researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, in collaboration with a team of archaeologists from Jerusalem’s City of David archaeological site, Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), and Tel Aviv University (TAU) have managed to produce a detailed chronology of Iron-Age Jerusalem when the city served as the capital of the biblical Kingdom of Judah.

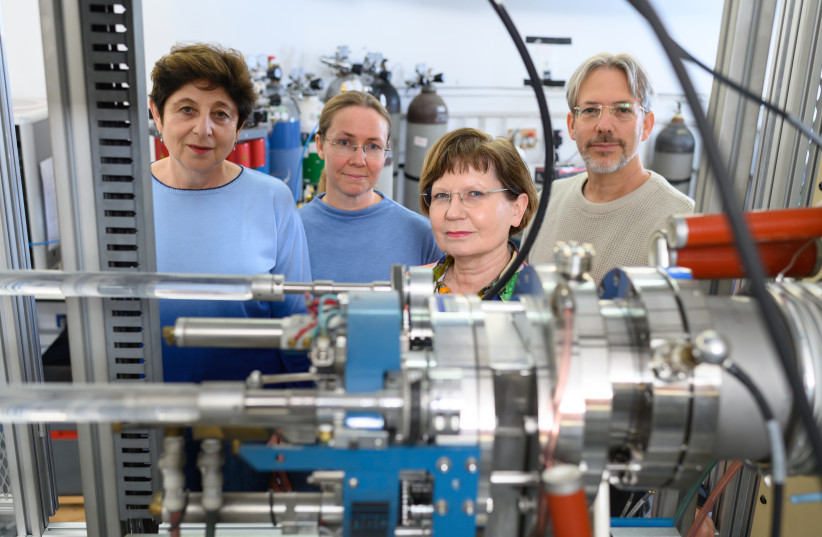

The findings of this study are being published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, (PNAS) under the title “Radiocarbon chronology of Iron-Age Jerusalem reveals calibration offsets and architectural developments.” The study was made possible by an experiment set up by Dr. Lior Regev at Weizmann’s Dangoor Research Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (D-REAMS) laboratory, the institute’s dedicated accelerator for research.

Challenges dating findings

DESPITE THE reams of writings about Jerusalem, studying its Iron Age has proven challenging in terms of absolute chronology, which involves determining the exact dates or time periods to which archaeological evidence belongs, as opposed to a relative chronology, which establishes the order of events based on similarities to architecture or ceramic evidence at other sites.

Part of the challenge is a phenomenon known as the Hallstatt plateau, which comes from a particular interaction of cosmic rays with Earth’s atmosphere at the time in question and interferes with the use of radiocarbon dating, the gold standard of determining how old something is. The plateau means that during the Iron Age, radioactive dating, rather than pointing to an object’s specific age, generates a graph with a flat area – the range between the 8th and 5th centuries BCE.

As a result, archaeologists exploring Iron-Age Jerusalem relied more on biblical and historic texts and studying pottery rather than using radiocarbon dating. In addition, the mix of architecture and continuous habitation over more than 4,000 years has led to Jerusalem being an amalgamation of construction from different time periods; it is a city that has seen many wars, destructions and reconstructions, turning into sprawling and complex urban areas built on top of the ruins of what came before.

Therefore, radiocarbon dating generally isn’t accurate during this time period, which made overcoming the Hallstatt plateau one of the biggest struggles in archaeological studies of the later part of the Iron Age.

As a result, archaeologists exploring Iron-Age Jerusalem relied more on biblical and historical texts and studying pottery rather than using radiocarbon dating. In addition, the mix of architecture and continuous habitation over more than 4,000 years has led to Jerusalem being an amalgamation of construction from different time periods; it is a city that has seen many wars, destructions and reconstructions, turning into sprawling and complex urban areas built on top of the ruins of what came before.

All these combined to create gaps in establishing an absolute chronology of Iron-Age Jerusalem. Filling these gaps would require successfully dealing with the Hallstatt plateau problem. Fortunately, the Weizmann researchers were able to do just that by using microarchaeology, a relatively new field within archaeological sciences that they had developed. This approach focuses on carefully examining pieces of evidence left behind at sites, using scientific instruments with an almost forensic-like level of care and attention.

“It’s a question of thoroughly understanding the connection between the materials to be dated and the layers with evidence of human occupation or construction material – and that’s how we were able to apply the microarchaeology method,” said Prof. Elisabetta Boaretto, director of Weizmann’s Scientific Archeology Unit.

DEVELOPED ABOUT eight decades ago, radiocarbon dating works by measuring radiocarbon (carbon-14 or 14C) in a given object. Radiocarbon is constantly being produced in the atmosphere and becomes part of the carbon cycle. These atoms are absorbed into the tissue of organic matter such as plants, animals and people – but when that living organism dies, it stops absorbing radiocarbon. The 14C undergoes radioactive decay, turning into nitrogen-14. Since radiocarbon has a known rate of decay, researchers can use the number of remaining 14C atoms to determine something’s age.

Going to the excavation sites in Jerusalem, Boaretto and Dr. Johanna Regev, a consultant in her lab, were able to carry out more than 100 radiocarbon measurements on organic material, mostly charred seeds.

“We have to be able not only to collect material like seeds, bones or charcoal from the site but to identify the context, such as where the seeds were burnt,” Boaretto explained. “We achieve this with the methods we have developed over the years, using analytical instruments that we have at Weizmann and also bring with us to the field. In this manner, we can go beyond the standard archaeological analysis of the site.”

The researchers then separated the original material from contaminants and carried out multiple radiocarbon measurements at the D-REAMS lab to get the highest level of accuracy and precision in dating. “We have an understanding of how the site was formed, so when we collect seeds or mortar samples related to the site, we can be confident that these were there when the site was built, which means we can date the site itself from that,” Boaretto said.

Overcoming the Hallstatt plateau was also made possible with the help of 100 calendar-dated tree rings obtained from well-known archives. Tree-ring dating, also known as dendrochronology, is built on the fact that a tree will grow a ring every year until its death. The more rings a tree has, the older it is.

Combining this with the radiocarbon method, researchers were able to obtain a more precise and detailed determination of the radiocarbon concentration in the atmosphere during the period of interest, which also helped create an absolute chronology.

THE EXISTENCE of two historical events that occurred at well-established dates – the 586 BCE destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians, and the 8th century BCE earthquake and subsequent widespread reconstruction efforts – helped provide further insights into the radiocarbon behavior in the atmosphere.

The researchers noticed differences between the radiocarbon in the material in the region compared to the measured concentration in European and American tree rings from the same time. These differences – when the radiocarbon data don’t match what we know they should be thanks to the tree rings – are known as “offsets,” and understanding them can be of fundamental importance for scientists studying the climate and atmosphere, as well as for archaeological chronologies.

The study’s greatest achievement was its success in creating an absolute chronology, with unprecedented detail and fidelity, for a continuously inhabited city. In particular, the researchers were able to provide concrete evidence of widespread presence of human habitation in Jerusalem as far back as the 12th century BCE. A westward expansion of the city was precisely dated back to the 9th century BCE by determining the timing of the construction of a large ancient building.

Establishing the dates of a major shake-up to the urban planning made it possible to attribute it to a devastating earthquake and further development up until 586 BCE. Notably, while previous research had credited the post-earthquake redevelopment to King Hezekiah, the radiocarbon dating and chronology show that it likely occurred during the reign of King Uzziah.

“Jerusalem is a living city; it’s not like a tel site that’s built as a sequence of layers,” Boaretto concluded. “This is a city that’s been rebuilt constantly all this time, and the archaeological evidence is scattered. But despite these challenges, layers and layers of construction and the Hallstatt plateau, we were able to put together its absolute chronology during the Iron Age.”

The methods developed in the study could have an impact beyond Jerusalem, the team said, “since problems with using radiocarbon dating at Iron-Age sites are a global issue.” The team’s microarchaeology approach can be used at many of these other sites, helping fill in the gaps in this pivotal period of human development and history. Not such a “small” feat for something called microarchaeology.