In prehistoric Israel, groups of hunter-gatherers were able to transmit the knowledge and skills most intimately connected to their identity to their children from generation to generation, while they maintained an exchange of technology and ideas at a more superficial level with different populations, research by Hebrew University archaeologists has suggested.

“Our idea was to track different populations living in the area in the Epipaleolithic period, roughly between 20,000 and 10,000 years ago,” said Dr. Francesco Valletta, lead author of a paper published in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology on Friday together with Prof. Leore Grosman.

“We were interested in understanding more about how populations who kept on returning to the same area over an extended period of time evolved,” Valletta added. “We are talking about the last hunter-gatherers in the Levant. In the following period, the Natufian, the first permanent villages were established.”

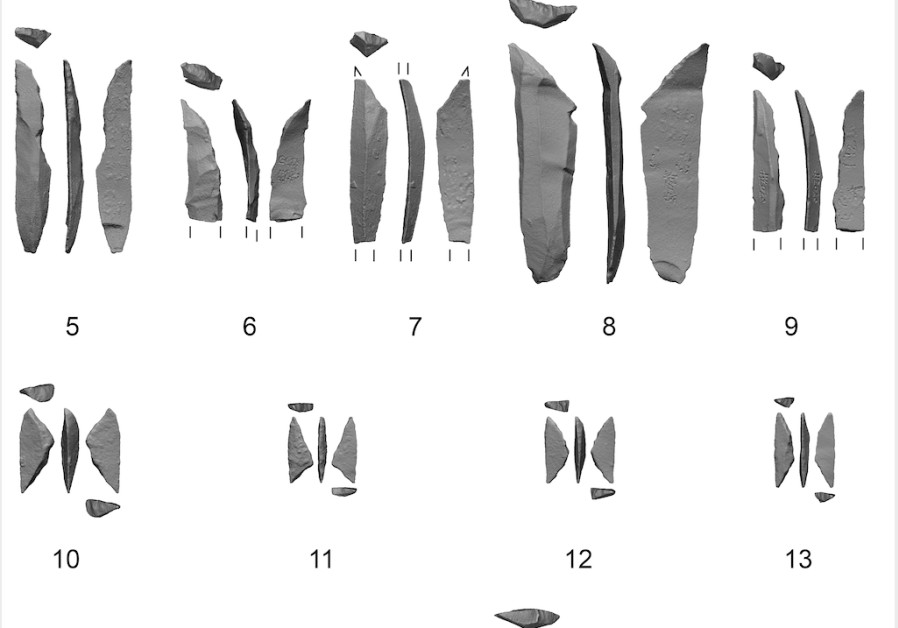

Paleontologists traditionally identify different cultural entities during the Epipaleolithic period based on the shape of the tools they produced, also known as microliths – small stone tools installed on a handle.

The researchers focused on the area of Ein Gev, near Lake Kinneret (the Sea of Galilee).

“Its main characteristic is that in a very limited space, less than a square kilometer, there are several prehistoric sites which were recurringly settled by different groups expressing different cultures,” Valletta pointed out.

He and Grosman considered three sites which were attributed to three groups.

In order to understand what kind of exchanges occurred between them, the archaeologists looked at their utensils and the way they manufactured them.

“Some technological innovations were easily replicable; others were more complicated to borrow, including the techniques to build stone tools,” Valletta pointed out. “These techniques usually were kept within the group, and this allows us to recognize a specific population through time, even if other cultural traits changed.

“What we found out is that in two of these sites, although the microliths presented different shapes, the artifacts were built in a similar way. Therefore, our conclusion is that we are not talking about two different groups but, rather, the same group, which, over the course of the millennia, evolved, but was still able to transmit its manufacturing techniques generation upon generation,” he highlighted.

“The development of a close connection between a specific group and a territory might have later evolved in an ever closer bond which emerged with the permanent settling and the establishment of the first villages,” he added.

The researchers also compared their findings from Ein Gev with artifacts found in other sites in the region. They found out that while the microliths presented similar shapes and therefore they might have been considered as manufactured by groups belonging to the same cultural entity, the techniques employed to produce them were actually different.

“Our interpretation is that characteristics that were easy to transmit, such as the shape of a tool, were shared between distinct populations, who therefore interacted and were able to swap ideas,” Valletta explained.

“Our suggestion is that more superficial cultural traits were exchanged in a vast network, while more intimate characteristics connected to the intimate cultural identity of the group were not shared with other populations,” he concluded.