One day Britain will unveil a striking new Holocaust Memorial and open the doors of a hi-tech learning center dedicated to helping visitors understand what happened during the Holocaust. At the moment, the project is on hold.

It was back in January 2014 that then-UK prime minister David Cameron, feeling that the UK had not done enough to memorialize the unique horrors of the Holocaust, set up a Holocaust Commission.

“The Holocaust is unique in man’s inhumanity to man,” ran its remit, “and it stands alone as the darkest hour of human history. Many organizations and individuals have worked tirelessly to ensure the memory of that atrocity remains alive, and its lessons continue to resonate today. Many survivors have played a crucial role by sharing their testimony. But we will not always have the survivors with us, and as the events of the Holocaust become ever more distant, they will feel increasingly remote to current and future generations.

“The Holocaust Commission will investigate what further measures should be taken to ensure Britain has a permanent and fitting memorial to the Holocaust, along with sufficient educational and research resources for future generations.”

It was not as though Britain had failed to commemorate the Shoah. A Holocaust Memorial had been set up in 1983 in Hyde Park, in the very center of London, and annual remembrance services for its victims were held at the site. Conceived as a garden of boulders surrounded by white-stemmed birch trees, the largest boulder is inscribed with text from the Book of Lamentations: “For these I weep. Streams of tears flow from my eyes because of the destruction of my people.”

In addition, there was a permanent Holocaust exhibition at the Imperial War Museum in south London, and a major extension to that was already being planned. The Wiener Library for the Study of the Holocaust and Genocide was a permanent academic unit within the University of London. There were also several other regional Holocaust centers.

Cameron’s commission called for evidence, and received some 2,500 submissions. Prominent among the responses was one of Britain’s largest ever gatherings of Holocaust survivors. On May 8, 2014, some 250 people who had suffered persecution in the Shoah met at the vast Wembley Stadium to contribute to Cameron’s national consultation on how the Holocaust should be remembered and taught in Britain.

In January 2015 the commission issued its report and recommendations. They were instantly accepted in full by the government and endorsed by the opposition. It recommended there should be a “striking and prominent” new memorial to serve as the focal point of national commemoration of the Holocaust. It should be prominently located in central London to make a bold statement about the importance Britain places on preserving the memory of the Holocaust. In addition a world-class learning center should head a campus devoted to national educational activity and the advancement of Holocaust education in every part of the country. It should be colocated with the memorial.

To help the government carry the project forward, it set up a UK Holocaust Memorial Foundation composed of eminent establishment figures, including the chief rabbi, Ephraim Mirvis. The foundation quickly embarked on a dual search – for a suitable location and a winning design.

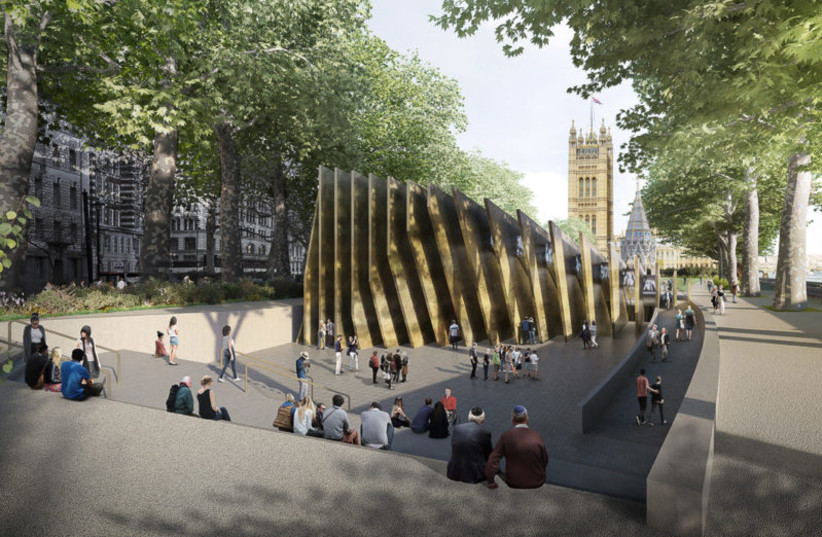

The design for the memorial was selected by way of an international competition which attracted 92 entries. In October 2017, it was announced that the winning design had been submitted by a team led by the British-Ghanaian architect Sir David Adjaye, which included Israeli designer Ron Arad and landscape architects Gustafson Porter and Bowman.

The memorial consists of 23 bronze fins, with the gaps between the fins representing the 22 countries where the Holocaust destroyed Jewish communities. Each gap acts as a separate path down to a hall leading into the Learning Center, along with a “contemplation court” and “hall of testimonies.”

Entering the memorial would be a sensory experience. The 23 bronze fins require the visitor to enter in an isolated, solitary way, each pathway planned as a different experience. Each path eventually leads down into a generous hall named the Threshold, which acts as a place of contemplation and transition into the Learning Center below ground. On leaving the memorial, the circulation route ensures visitors emerge to see the classic uninterrupted view of Parliament – and the reality of democracy.

“The complexity of the Holocaust story,” said Adjaye when the winning design was announced, “including the British context, is a series of layers that have become hidden by time. Our approach to the project has been to reveal these layers... to create a living place, not just a monument to something of the past. We wanted to orchestrate an experience that reminds us of the fragility and constant strife for a more equitable world.”

THE SITE chosen and agreed by the government was controversial from the very start. The foundation settled on Victoria Tower Gardens, a small area of parkland adjacent to the Houses of Parliament. Countless objections from eminent figures argued against the site on a wide variety of grounds. Finally, the objectors took their case to the High Court, and have recently won. Victoria Tower Gardens is ruled out.

Since the approved design was conceived specifically for that location, that, too, is now under question. The government is considering its position.

That Britain will one day present a new Holocaust Memorial and Learning Center to the world is beyond doubt – the project has been approved unanimously by government and opposition. But what the structure will look like and where it will be sited – these matters are still hidden in the mists of the future.