In May 1933, four months after Adolf Hitler became the German chancellor, thousands of students marched in a torchlight parade that culminated in a massive book burning in a square opposite the University of Berlin. As the students added volumes written by authors the Nazis despised, an announcer declared: “Against the soul-destroying overestimation of the sex life – and on behalf of the nobility of the human soul – I offer to the flames the writings of one Sigmund Freud.”

“Against the soul-destroying overestimation of the sex life – and on behalf of the nobility of the human soul – I offer to the flames the writings of one Sigmund Freud.”

University of Berlin book-burning announcer

Freud initially downplayed the incident: “What progress we are making,” he wrote. “In the Middle Ages, they would have burnt me; nowadays they are content with burning my books.” Nonetheless, Freud supported the decision of non-Aryan psychoanalysts and his sons, Oliver and Ernst, who were working in Berlin, to leave Germany.

But he resisted advice from friends and colleagues to leave Vienna. “The brutalities in Germany seem to be diminishing,” he told them, and “despite the suppression of us Jews,” he was not in any personal danger, he said. Having cited additional reasons for his decision – his age, ongoing treatments for cancer of the jaw, attachment to his home and possessions – Freud confessed that “probably, I should stay even if I were in full health and youth.”

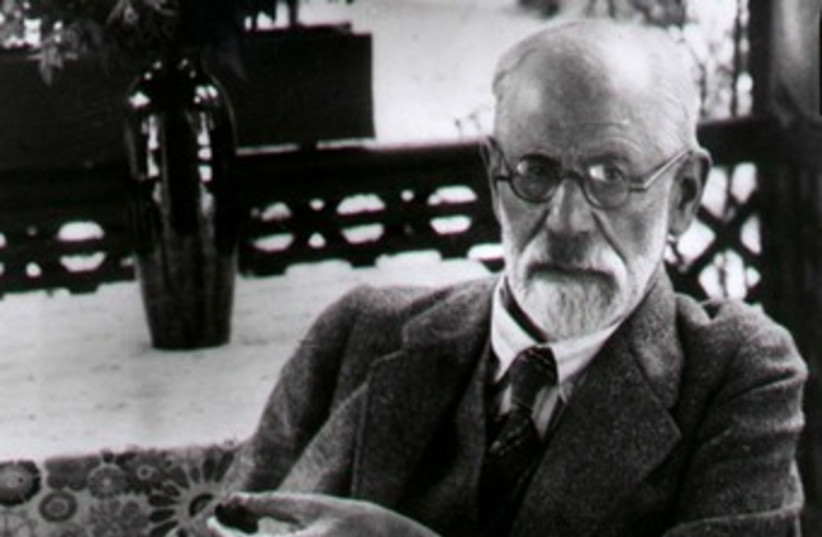

In 1938, just after Germany absorbed Austria into the Third Reich, the 81-year-old founder of psychoanalysis immigrated to London.

In Saving Freud, Andrew Nagorski (a former bureau chief at Newsweek and author, among other books, of Hitlerland, The Nazi Hunters, and The Year Germany Lost the War) reviews Freud’s life and provides biographical sketches of the eclectic group of people who helped rescue him as the Gestapo was closing in: Ernest Jones, president of the International Psychoanalytical Association; Anna Freud, Sigmund’s daughter; William Bullitt, a former US ambassador to Russia and France; Marie Bonaparte, Napoleon’s great-grandniece, princess of Greece and Denmark, and a patient of Freud’s who became a psychoanalyst; Max Schur, Freud’s physician; and Anton Sauerwald, a Nazi bureaucrat.

How Sigmund Freud was saved from the Gestapo

Nagorski’s account of the life and work of Freud and his circle will be familiar to many readers. It is at its best when Nagorski captures Freud’s ambivalence about leaving Austria. In 1933, we learn, Freud reported to Jones that “despite all the newspaper reports of mobs, demonstrations etc., Vienna is calm, life undisturbed.” He expected “with certainty that the Hitler movement will spread to Austria,” but thought it unlikely the Nazis would present “a similar danger there as in Germany.”

His confidence – or, more precisely, his will to believe – rested on a peace treaty that made it illegal to strip minorities of their rights, the likelihood that the League of Nations would intervene to protect Jews, and his sense that “our people are not quite so brutal.”

Then again, Freud also acknowledged that “the world is turning into an enormous prison. Germany is the worst cell. What will happen in the Austrian cell is quite uncertain.”

In 1937, Freud admitted that the Nazi invasion probably could not be checked – and hoped he would not live to see it himself. In February 1938, however, he told a colleague, “Our brave and in its way decent government is now more energetic than hitherto in keeping the Nazis at bay.”

THE DETENTION and interrogation of Anna, his beloved daughter, by the Gestapo at the end of March, Nagorski writes, “was almost certainly the moment when Freud abandoned any remaining doubts about the need to emigrate.”

Surprisingly, the rescue of Freud occupies only a small fraction of Nagorski’s narrative. Enough, however, to demonstrate that it took a village to get him from Vienna to London. Bullitt, Nagorski speculates, maneuvered to get John Wiley, his close friend, appointed US consul general in Vienna so that he could “spring into action” if Freud was at risk.

Knowing the Gestapo was watching, Wiley ordered an embassy car displaying an American flag to be parked outside Freud’s residence. And Bullitt informed Hugh Wilson, the American ambassador in Berlin, that he would pay whatever was necessary if the Nazis demanded a ransom.

Marie Bonaparte smuggled documents from Freud’s massive collection of correspondence out of the apartment, and ended up covering the expenses associated with the departure of the family from the residence and office at Berggasse 19.

Ernest Jones performed the herculean feat of persuading Sir Samuel Hoare, England’s home secretary, to issue entry permits for 18 adults and six children.

In a bizarre quirk of fate, Anton Sauerwald – whom the Nazis had appointed to oversee Freud’s holdings and who agreed that, however deplorable, Jews had to be “eliminated” – became impressed by Freud’s erudition, his theories, and the man himself. And so, when he discovered evidence that could have prevented Freud from emigrating, Sauerwald locked it up until the family was gone.

And Anna handled innumerable procedural details, even when it meant contending with Nazi bureaucrats and thugs.

Throughout the ordeal and his personal war with chronic pain, Nagorski reveals, Freud showed no signs of impatience, and retained his composure, pride, sense of irony, and equanimity in the face of death. Forced to sign a document declaring he had been well treated by the Nazis, Freud asked if he could add one sentence: “I can heartily recommend the Nazis to anyone.” In a statement recorded by the BBC from his new home, Freud proclaimed, “At the age of 82, I left Vienna as a result of German invasion and came to England, where I hope to end my life in freedom.”

On September 23, 1939, Freud died. “He was always a deeply human and noble man,” Max Schur recalled. In his poem “In Memory of Sigmund Freud,” W.H. Auden captured Freud’s legacy: “To us he is no more a person/now but a whole climate of opinion.”

The writer is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Professor of American Studies at Cornell University.

Saving Freud

By Andrew Nagorski

Simon & Schuster

356 pages; $28.99