Bruno Schulz was born in 1892 in Drohobycz, a Galician satellite of Lwow, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. During his childhood, Jews constituted 40% of the town’s population, Poles 35% and Ukrainians 30%. Before he was murdered by an SS officer in 1942, Schulz published two volumes of short stories – Cinnamon Shops; and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass.

His visual art, which included self-portraits and scenes of Jews gathered around festival tables, often depicted sexualized, statuesque, imperious women, who scorn prostrated men, anticipating pleasure and expecting blame.

Dismissed as decadent and anti-realist by Communist authorities in the 1940s and ’50s, Schulz was rediscovered and lionized in the second half of the 20th century for his postmodern explorations of dreams, illusions, and nightmares. Schulz “might have given us untold treasures,” declared Isaac Bashevis Singer, “but what he did in his short life was enough to make him one of the most remarkable writers who ever lived.”

Israeli novelist David Grossman indicated that Schulz gave him “for the first time, the key to writing about the Holocaust – not about death or destruction, but in truth, about life itself.”

The haunted life of Bruno Schulz

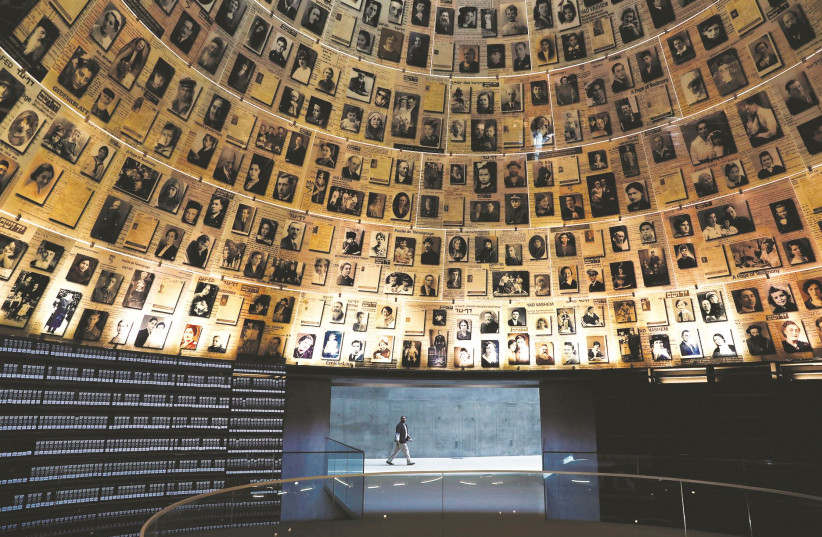

IN HIS book Bruno Schulz, Benjamin Balint (author of Kafka’s Last Trial and co-author of Jerusalem: City of the Book) “conjures a portal into the haunted life of this virtuoso of language and image.” Balint also examines the international controversy surrounding the discovery in 2001 of murals drawn by Schulz, which were then smuggled to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem by three Israeli agents, aided by bribes and diplomatic immunity, as part of the Jewish state’s policy of kinnus, an ingathering of artifacts to promote cultural continuity.

Subject to “hypochondriacal musings,” Schulz, Balint reveals, complained that teaching at the Drohobycz Public Secondary School was incompatible with his artistic aspirations. He attributed his frequent bouts of depression to “the sadness of life, fear of the future, some dark conviction that everything is headed for a tragic end.”

Unwilling to abandon his ailing sister by moving to Warsaw, a decision that ended his engagement to Jozefina Szelinska, Schulz became destitute and dependent on rations when the Nazis took control of Drohosbycz. In 1942, he accepted “protection” and status as a “necessary Jew” offered by SS Hauptscharfuhrer Felix Landau, a sadist with suppressed sexual proclivities, who enjoyed playing executioner and gravedigger in exchange for painting his portrait, portraits of the girlfriends of Gestapo officers and murals.

“I am not made to offer resistance. to stand up for myself, to defy the will of another person. I don’t possess the necessary strength of conviction… for that.”

Bruno Schulz

“I am not made to offer resistance,” Schulz had acknowledged, “to stand up for myself, to defy the will of another person. I don’t possess the necessary strength of conviction… for that.”

On November 19, 1942 – the day the Soviet Union began a massive offensive to seize Stalingrad from the Nazis, and when Schulz planned to escape Drohobycz with forged papers – a Jewish pharmacist shot a German guard in the finger. Gestapo officers received permission to retaliate. Schulz was among the 160 to 230 Jews murdered on what was subsequently called “Black Thursday.”

Landau was imprisoned when World War II ended, escaped, was arrested in 1958, convicted four years later, and given a double life sentence. Although he remained unrepentant, his sentence was commuted in 1973, and he was released from prison. He died in 1983.

By then, major exhibitions of Schulz’s drawings, films based on his stories, and translations of his books into many languages had appeared, along with rumors (still unconfirmed in 2023) that Messiah, his urtext, existed in a KGB archive. On February 9, 2001, a documentary filmmaker found a Schulz mural in a pantry that had been the playroom of Landau’s son.

BALINT ACKNOWLEDGES that “Operation Schulz” a “forced aliyah,” violated Polish, Ukrainian, and international laws protecting registered cultural artifacts from exportation. In 2008, Israel and Ukraine signed an agreement permitting the disputed artwork to remain at Yad Vashem “on loan” for 20 years.

Important questions, Balint suggests, remain unanswered. To which country does Schulz’s legacy really belong? Does it matter that Schulz wrote his stories in Polish, was not a Zionist, renounced his Jewish faith when he contemplated marrying a Catholic, and made no specific references to Jews in his fiction? Or should he be a posthumous beneficiary of the Law of Return because his homeland no longer really exists, except perhaps for the small number of Jews who still live in Drohobycz, and he was a victim of the Holocaust?

Balint concludes his beautifully written, informative and thoughtful book with an answer, of sorts, to these questions. In the “truceless contest between peoples, and in the struggle to shape their afflicted and unappeased pasts,” he writes, “our admission into Schulz’s own myth-making has become occluded. But if we strive beyond the prosaic facts of history, maybe we’ll see that a poetry also thrums in the longing to restore Bruno Schulz in his homeland, wherever that might be.”

The writer is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Professor of American Studies at Cornell University.

BRUNO SCHULZ: An Artist, A Murder, and the Hijacking of History

By Benjamin Balint

W.W. Norton & Company

288 pages; $30