‘Dr. Rathenau was struck by at least eight bullets,” reported The New York Times on June 22, 1922. “A hail of bullets, one of them striking him in the throat and passing upward to the brain,” and several hand grenades left the German foreign minister no chance.

The fabled industrialist who headed the AEG conglomerate and ran the German economy during World War I was assassinated not because of his wealth, and not because of his record, but because he was Jewish, which is why his murder is often seen as a harbinger of his country’s Nazi future.

Rathenau’s death was particularly proverbial because his solution to what antisemites called “the Jewish problem” was that the Jews do what he did: assimilate.

No less ironically, Rathenau was in government not because he needed power’s perks, but because, like so many other Jews, he wanted to mend the world, so much so that he advocated banning luxury production, and thus freeing private capital to spur spiritual wealth. Aged 55 when he died, Rathenau’s eventful life thus mixed big business, humanism, and a troubled Jewish soul.

The very same mixture has animated the life of financial wiz George Soros.

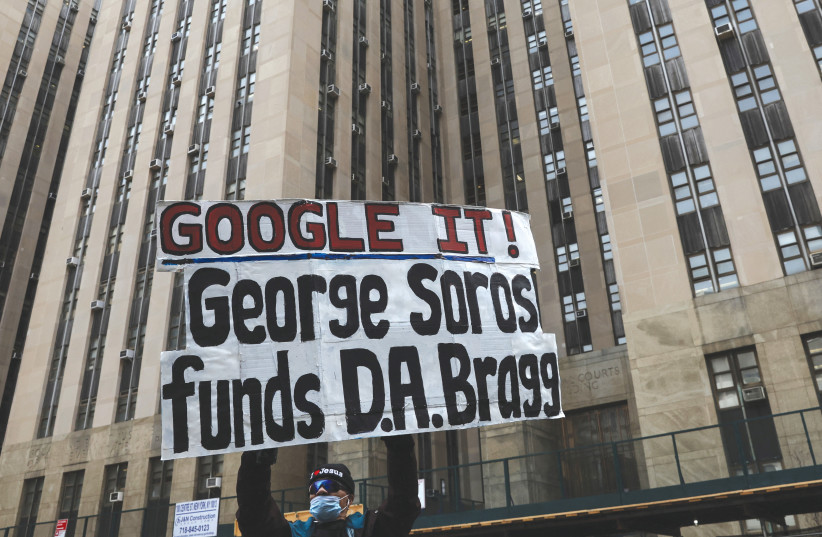

Fortunately, the 93-year-old punching bag of the Populist International is alive and well. Unfortunately, Soros has just been attacked by a major personality in a way that is reminiscent of the antisemitism Rathenau faced in his life, and calls for every Jew to stand by Soros. That includes this writer, who over the years was critical of our generation’s richest Jew.

RATHENAU’S effort to flee his Jewish identity was for Soros a part of his childhood, having been raised in interwar Budapest by affluent parents who changed their very Jewish name, Schwartz, to the Hungarian Soros.

The name change didn’t help when the Nazis arrived, and the teenager went through the experience of being hounded for being a Jew, hiding in Budapest until its liberation. Soros then proceeded from a degree in the London School of Economics through a job as a clerk in a merchant bank to the fabled currency-trading career that made of him a billionaire.

The business of currency trading is easy to misinterpret. Economically, many don’t understand the utility of traders judging, through their deals, any government’s economic conduct. Morally, this trade’s detractors don’t understand the risks it involves.

In Soros’s case, the two sides of his trade’s image, the fair and the unfair, became apparent in two memorable events. The first happened in 1992’s Black Wednesday, when he dumped £10 billion at a time when Britain, bound to the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, failed to raise interest rates when it should have, thus behaving as if its currency was stronger than it actually was.

The subsequent run on the pound led to its devaluation and to Britain’s abandonment of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. Soros is believed to have made that day £1b.

The move, before which few knew his name, did not spark antisemitic attacks. It was seen for what it was: a gutsy businessman’s legitimate gamble that flashed a much-needed red light in the face of a financially conceited government.

Things were entirely different three years later, when a host of Asian currencies collapsed and Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad said “it is a Jew who triggered the currency collapse.”

Ironically, it later turned out that Soros did not sell one Malaysian ringgit those days, but that didn’t matter. As happened to him when the Nazis chased him, Soros now unwittingly assumed the role of antisemitism’s stereotypical Jew, the medieval money changer who was allegedly out to swindle, dispossess and conquer the non-Jewish world.

While this was happening to his Jewish identity on the financial side of his activity, what was happening on Soros’s philanthropic side was no less ironic, and even more tragic.

Eager to better the world, Soros began deploying his fortune to advance freedom and prosperity throughout the world. What began during the Cold War with assistance to dissident movements, like Poland’s Solidarity and Czechoslovakia’s Charter 77, was later followed by opening business schools in the postcommunist world and financing infrastructure projects in the Third World.

Antisemitism against Soros cannot be tolerated from anyone

Ultimately, Soros headed a multibillion-dollar effort so vast that at one point he was the world’s second-largest foreign-aid provider, just after Japan, and ahead of (!) the US.

To antisemites this generosity represented not the idealism and generosity with which it is obviously imbued, but the conspiracy theories with which they are infected.

Soros, for his part, could indeed be tactless. As this column argued last decade (“By George,” 14 July 2017), promoting Muslim immigration into Hungary without living there was both unfair and unwise, and such was also Soros’s claim the previous decade that antisemitism “is the result of the policies of Israel and the United States” (“The sorrows of George Soros,” 21 November 2003).

However, such criticism cannot license denying Soros’s philanthropic greatness, as maverick carmaker Elon Musk just did in a tweet that claimed Soros “hates humanity” and that his endeavors are designed “to erode the very fabric of civilization.”

Such an underhanded attack must make every Jew, regardless of ideological inclination or political stripe, defend Soros.

Musk, whose own philanthropy has been attacked for reportedly adding up to hardly 1% of his wealth, and for having been occasionally channeled to his business partners, is livid because Soros sold his stake in Musk’s Tesla.

That can explain the impulsive Musk’s anger, but it cannot justify libel, let alone antisemitic vitriol, even if aimed at the controversial Soros, a mogul whose treatment of his wealth could hardly be more idealistic, generous, and Jewish.

www.MiddleIsrael.net

The writer, a Hartman Institute fellow, is the author of the best-selling Mitz’ad Ha’ivelet Hayehudi (The Jewish March of Folly, Yediot Sfarim, 2019), a revisionist history of the Jewish people’s political leadership.