The Toby Press sent me a gift in 2019 of a book dealing with the use of the “Hebrew Bible” in the United States. The book is appropriately titled Proclaim Liberty Throughout The Land,” the biblical verse which is on the Liberty Bell.

Four scholars prepared the volume under the leadership of Prof. Meir Soloveichik, an academic and pulpit rabbi in New York.

Since Abraham Lincoln’s birthday is at hand (the date was February 12, 1809; his birthday is celebrated as a holiday in the US), I have chosen to select a quote of his in the book based on a biblical verse – one way of demonstrating how important the Bible was to Lincoln.

He applied the verse from Psalm 19, “The fear of the Lord is clean, enduring forever; the ordinances of the Lord are true, they are righteous altogether.”

In his second inaugural address, in 1865, Lincoln applied the spirit of the verse in this manner.

“Fondly do we hope, fervently, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.” Then he made an important point.

“Yet, if God wills that it continue until the wealth piled up by the bondsman’s 250 years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said.”

And then President Lincoln quoted the biblical verse on which his point was based: “The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.” He saw the translation as “judgments” rather than that as “ordinances.”

The inspiration of the Bible for him is very clear and repeats itself with different verses on numerous occasions.

From this work, I learned quite a bit, and now my purpose in this article is to show how Lincoln’s triumph and death were portrayed in a Hebrew newspaper of the time of the Civil War.

In my youth, when I memorized and recited the Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, I never thought that I would have the opportunity to write about him.

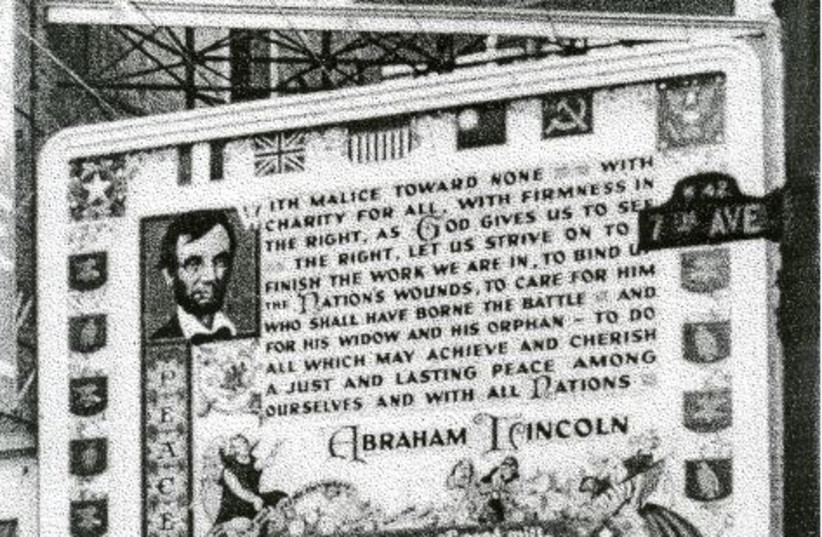

I have been fortunate that the noted collector Irvin Ungar, who, over two decades, located and purchased the unknown works of the noted artist Arthur Szyk, has helped me better understand the great leaders of the United States. This article about Lincoln is adorned with the works of Szyk, which are most significant.

THERE WAS a time in the ’80s when some of the major libraries in Jerusalem had bound volumes of the English-language and other language newspapers of England, Paris, New York, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem on the shelves. Two libraries I enjoyed were the National Library of Israel and the Ben-Zvi Institute library. Now, alas, there is no room on the shelves for these historical volumes, so they have been warehoused. You can order any volume you want, but you never know when you will receive them.

At Ben-Zvi, my quest was very fruitful, since the Hamagid newspaper had an American correspondent, Rabbi Henry Vidaver, serving a congregation in St. Louis. He covered many Lincoln activities. Then Vidaver wrote quite a bit about the assassination and its impact on the Christian and Jewish communities.

Hamagid, published between 1856 and 1903, has a street named after it in Jerusalem. This was an early Hebrew newspaper. Because of the harsh censorship problems in Russia, the paper was first published in Lyck, Prussia. After 1890 the paper was published in Berlin, Krakow and Vienna.

Eliezer Lipman Silberman founded the paper and set the tone. The paper offered a point of view of moderate religious Orthodoxy at that time. The paper’s circulation was never more than 1,500, but it was passed from hand to hand, so it had a large readership. The man on the spot in the US was Vidaver.

Prof. Jonathan Sarna evaluated Vidaver and the paper in this fashion. “I don’t think that Hamagid paid much, but Vidaver became well known for writing in the Hebrew paper. His articles linked him back to the world of Hebrew-speaking learned Jews.”

Even though Vidaver was a rabbi in St. Louis, he received most news by telegraph, the fastest communication device of that era. Hebrew scholars believe his reputation was built on the way he could tell a story rather than report a story.

In Sarna’s most informative volume Lincoln and the Jews we discover how our Yankee coreligionists back in the 19th century had such a love for Lincoln, and he for them. The Jews in the Confederacy were not pleased with his pro-abolitionist views and his Emancipation Proclamation.

Surprisingly, there is only one modern Hebrew book on Lincoln. It was translated from an English biography by Yaakov Burla. As a part of the book, he translated the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address. When Israel issued some translations of the Gettysburg Address, Burla’s was used.

We join Vidaver as he reported via Hebrew from the US.

“The end of the month of April.” Now, he gets to the news: “From the time I sent you my last dispatch – mighty acts has God performed, which could be readily seen in the eyes of the citizenry of this country.

“The majority of the American population knew the ‘Land of the South’ had weakened and its strength waned daily, with the capital, Richmond, Virginia, possessing only a few more days to survive.”

Vidaver then described the process leading to the final stages of the four years of bloody struggle: “No one was ready to announce that the end was at hand, but the Southern commanders, one by one, began surrendering quickly to their Northern opponents.”

Then Vidaver asked the key question, based on his biblical expertise “Who can fathom the secrets of God, and who can know his plans? Suddenly, a strong voice is heard in the land that General Lee, the Confederacy commander-in-chief, had surrendered to General Grant, the Northern commander-in-chief. All the Confederate troops followed the lead of General Lee. Richmond, the South’s capital, had fallen into the hands of the Northern leaders and would never rise again.”

Vidaver stressed that “Lee halted the fighting because he realized that continuing on would shed innocent blood.... Grant, on his part, offered peace terms to Lee which contained the spirit of love parallel to the expression of comfort when death was at hand.

“The victory paved the way for the path to peace. When the announcement was made that Richmond had fallen, great was the joy of the North, but the entire nation, in its enthusiasm, shouted out ‘Heydad, heydad’!”

“When we discuss Lincoln and the Jews,” Sarna explained, “it has to do with which Jews and when. The assassination rapidly turned Lincoln into a Jewish saint. By then he had won the war, overturned the expulsion order of Jews by Grant and ensured that Jews could be chaplains in the Union Army in 1862 (the Confederate Army had done it earlier in the war). Northerners and Jews in Yankee land were devastated by his death.

“The Confederate Jews were not as overwhelmed by this leader’s demise. Even the noted Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, founder of the Reform movement in the US, had his doubts regarding Lincoln. For most Jews, Lincoln became Moses unable to enter the land of peace.”

The joy, described earlier, did not last long, as can be seen in the continuation of Vidaver’s story. “On the day (Passover) that we recited (in the Hallel prayer for the holiday) ‘This is the day that God has created, we should rejoice and be happy thereon’ this became a day turned upside down into one of clouds and overcast; this was an accursed day for the citizens of the United States.

“A voice was heard wailing! Abraham Lincoln, the president of the United States, has been assassinated by a murderer who lay in wait for him in the theater.”

Vidaver then described how Lincoln and his family had come to the theater to celebrate with citizens of the nation. “But a man came from behind the curtains and shot Lincoln in his forehead and killed this tzaddik. What a terrible crisis was aroused in the minds of the American people. All that could be heard was the sound of weeping and great anguish... the windows of every hope were draped in black.”

Continuing his account of why this happened: “It was the hatred of the South, which had lost the war on the field of battle, that caused the death of a great man via an individual with his deadly weapon who murdered his soul, because the assassin was hired by the Confederacy to perform this deed,” Vidaver wrote, espousing the conspiracy theory for Lincoln’s death arranged by Southern leaders.

This conspiracy theory was felt so strongly that the Jewish secretary of the Treasury of the Confederacy, Judah P. Benjamin, became the main culprit in the minds of the North.

Without much knowledge of the whole Lincoln assassination story, I received a book at age 10 or 11, Mr. Benjamin’s Sword. In that work Benjamin becomes a hero as he has a murky escape to England. There, in Great Britain, he becomes a noted barrister. The book also describes him as the first Jewish senator in the US, from the state of Louisiana.

In Lincoln and the Jews, Sarna points out, one noted rabbi, Isaac Leeser of Philadelphia, heard the news from his president “during the pause in the morning service, when the Torah Scroll was taken out.”

A telegraphed message reached San Francisco later in the morning. “[Rabbi] Elkan Cohn of Congregation Emanu-El handed a note with the news just as he was ascending his pulpit, on Saturday, to deliver the usual sermon.... He was so overwhelmed that, bursting into tears, he sank almost senseless.”

The day after Passover (Lincoln was killed on Shabbat Hol Hamoed Passover) there was a call for memorial services for Lincoln in every church and synagogue throughout the country.

Vidaver’s own synagogue in St. Louis was packed with men, women and children, Christians as well as Jews. “I spoke in English, expressing our anguish for the death of this great leader. My words had their impact on those assembled... so soon they will be printed and distributed.”

Emanuel Hertz, the brother of Chief Rabbi Hertz of England, collected all the Jewish sermons, which were published as a book. Vidaver’s was included.

The American Jewish interest in Lincoln has continued through the years, especially resonating in the new work by Sarna.

In my search of the issues of the Young Judaea monthly magazine from World War II at the National Library, I discovered a member’s black-and-white drawing of Lincoln with small drawings of his biography. ■