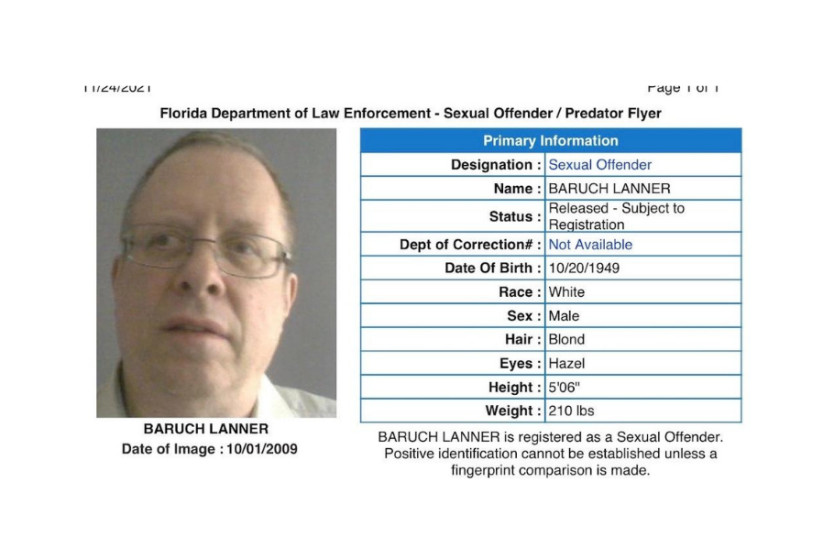

It’s been over 20 years since my predecessor as editor of the New York Jewish Week, Gary Rosenblatt, first exposed the predations of Rabbi Baruch Lanner. His powerful investigation led Lanner’s bosses at the Orthodox Union to issue a report describing the sexual, physical and emotional abuse carried out by Lanner against dozens of teenagers in his charge.

It’s been exactly 20 years since Lanner was convicted of sexually assaulting students at a Jewish high school in New Jersey.

It’s been 14 years since Lanner, then 58, was released after serving three years at Southwoods State Prison in Bridgeton, New Jersey.

And yet Lanner continues to haunt Jewish communal life, in his corporeal self and as a symbol of how Jewish institutions address sexual abuse in their midst.

In December, five alleged victims sued Lanner and his former employers under New Jersey law that allowed cases to be pressed despite the passing of the statute of limitations. And last week Haaretz reported that Lanner is now in Israel, where he was given temporary residence status and feels confident that he will be given Israeli citizenship.

In the years since Lanner’s exposure and conviction, there has been notable progress. There is a robust nonprofit sector that advises synagogues and other institutions on how to create safe spaces and report offenders.

Last year leaders of the Reform and Conservative movements mounted investigations of abuse and cover-ups within their ranks, and named names. “Lookback” laws have allowed plaintiffs to demand accountability from individuals and institutions decades after their alleged abuse.

And yet, as the latest twist in the Lanner story shows, advocates for abuse victims are frustrated by how many institutions still don’t seem to get it. Also last week, my colleague Philissa Cramer reported on the death of a Satmar Hasidic cantor, Baruch Lebovits, who was lauded in the haredi Orthodox press and at two separate funerals despite his conviction for repeatedly sexually abusing a 16-year-old boy.

Lebovits himself embodied and symbolized the dysfunction in the haredi Orthodox community, where victims are still discouraged from contacting local law enforcement and, and, as reporting has frequently shown, leaders are more likely to ostracize the accusers than the accused.

“Communal structures protect abusers by placing them in another shul or another school or whatever,” Elana Sztokman, author of a new book on abusive rabbis, told Andrew Lapin. “Because abusers often are people with power, so power protects power. It’s really hard to push back against, because you’re pushing back against networks of power.”

What should this mean for Israel?

Now activists are pushing back against the power of the Israeli government, reminding officials that they are under no obligation to grant citizenship to an ex-con like Lanner. I spoke Thursday with Shana Aaronson, who directs Magen, an Israeli advocacy organization that deals with sexual abuse, especially in the Orthodox community. She told me that she has known about Lanner’s intention to make aliyah since 2019, and that she alerted Israeli authorities. Despite Israel’s Law of Return, set up to grant nearly automatic Israeli citizenship to Jews the world over, the Foreign Ministry has it in its power to reject applicants who pose a threat to Israeli society. (See under: Lansky, Meyer.)

Apologists might suggest that Lanner has done his time, and should be able to move on with his life in the Jewish state. Aaronson rejects this on moral and legal grounds. First, he faces that civil suit, and moving to Israel would put him all but out of reach of the U.S. courts. Lanner is also listed on sex offender registries in the United States, which would be moot were he to move to Israel. At least in theory, he could find a job there working with kids.

Perhaps most egregiously, granting Lanner citizenship would signal to other offenders that Israel is a safe haven for the accused and the convicted. “We have a list of about a hundred offenders in 15 years who have moved to Israel to escape – whether it was actually criminal or civil proceedings, or things have started to get hot for them” abroad, said Aaronson.

A Foreign Ministry spokesperson told Haaretz that the Lanner case “will be thoroughly examined,” but Aaronson says he shouldn’t have gotten the courtesy of a residency visa.

“For the government to make such a morally bankrupt decision, despite efforts by organizations like mine and aliyah agencies, is really, really upsetting,” she said.

The Jewish Week investigation of Lanner was a landmark, and, despite anger and backlash from powers that be, led to a reckoning within Jewish institutions. But as last week’s news suggests, that reckoning is hardly complete. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of JTA or its parent company, 70 Faces Media.