NEW YORK — A hand-drawn portrait of a young man in a French internment camp. A photo of a Jewish girl who survived the Holocaust by hiding in a monastery. A letter detailing efforts to improve life for Jews in the Bergen-Belsen displaced persons camp.

These are just a few of the 250 artifacts that the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has collected recently through a drive launched last month — around the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz — to collect Holocaust-era artifacts from New Yorkers.

Most of the objects, including photographs, letters, documents, drawings and books, were donated by families of Holocaust survivors.

Fred Wasserman, the acquisitions curator for the museum’s New York office, described collecting the materials as “a race against time,” since the population of Holocaust survivors is aging and many have already died.

“It really is a matter of rescuing the evidence while we still can so that we can preserve this for future generations,” he told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

The Washington, D.C.-based museum decided to focus on New York because the city and surrounding area is home to a large population of Holocaust survivors and their descendants. The artifacts will join the museum’s vast collection and many will be digitized.

Here are nine standout artifacts collected through the project:

A hand-drawn portrait of a young man in an internment camp

After the German annexation of Austria in 1938, 19-year old Annie Windschauer left Vienna and followed her boyfriend, Fred Marot, to France. Marot was interned at Camp Bourg-Lastic in the Puy de Dome region. There he met a talented inmate, Felix Kalischer, who drew his portrait, which Marot sent to his girlfriend. Marot and Windschauer, in the small photo, survived the war and both eventually moved to the United States.

A photo of three Polish young women wearing yellow stars

This photo shows, from right to left, 17-year-old Ruchla Brukner with her friend Mindla Stahl and Brukner’s cousin Fajgla Blada in their hometown of Slawkow, Poland, in 1940. The three young women are wearing the yellow stars that Nazis forced Jews to wear. All three survived the war, with Brukner enduring two concentration camps together with her sister Esther.

A photo of the Judenrat in Slawkow, Poland

During World War II, Germany required every Jewish community under its rule to establish a local council. The Judenrat, as it was called, had to ensure that Nazi regulations were implemented and provided basic community services. This photo shows members of the Judenrat in Slawkow posing by a sign that reads “Hunger, cold and illness are our greatest enemies. Fight them successfully with the Jewish Winter Welfare.”

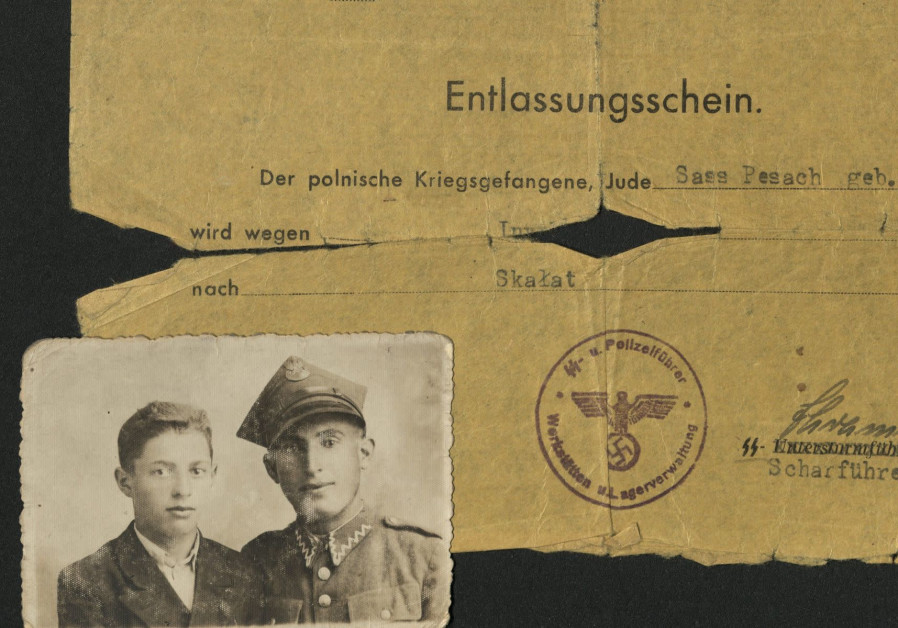

A discharge pass for a Polish Jew held in a German POW camp

Pesach Sass was a Jewish soldier in the Polish army who was captured by the Germans and put in a POW camp. But Sass, who can be seen in the photo in his uniform sitting next to his younger brother Shaya, got sick and was granted a pass to return to his hometown of Skalat. He arrived there just as the town was hit by typhoid and contracted the disease. He eventually recovered and survived the war by hiding in the woods with other family members and then fleeing to Italy.

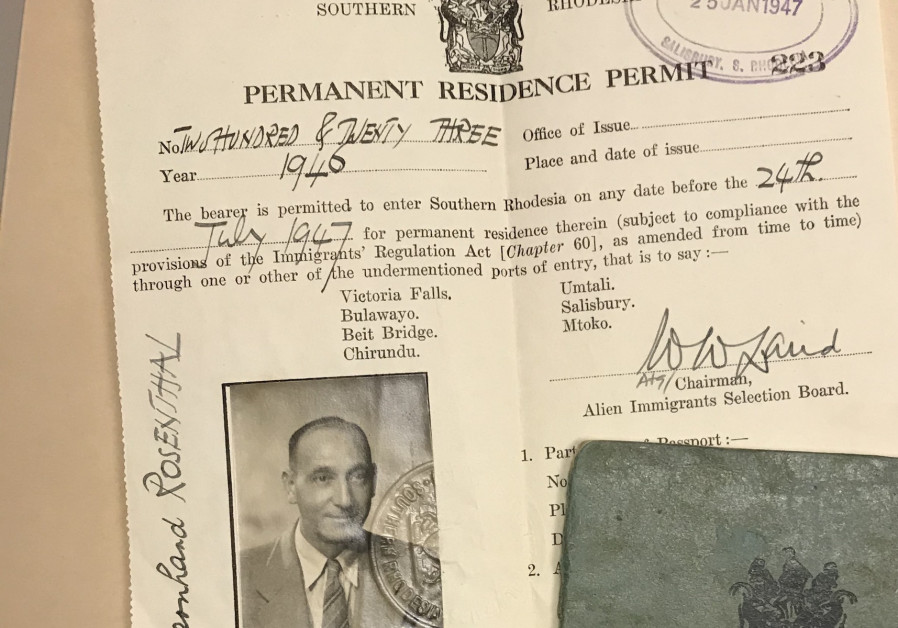

A German refugee’s pass to settle in Rhodesia

The only place that agreed to take in Bernhard Rosenthal was the British colony of Rhodesia, which today is Zimbabwe. He left Germany to settle there in 1938 and his wife, Hedwig, and their two children followed soon after. In Rhodesia, Bernhard was considered an enemy alien and had to check in with authorities every two weeks.

A photo of a young Jewish girl who took shelter in a monastery

Morris and Maria Zimmerman decided to hide their young daughter with nuns at a monastery. The couple from Bratislava, which is now part of Slovakia, eventually was deported to Theresienstadt but survived. When they tried to reclaim Hannah after the war, the nuns initially were reluctant to return her but eventually did. The Zimmermans later moved to the U.S. with the help of a cousin in Detroit, who signed an affidavit of support for them, which is shown here in the background.

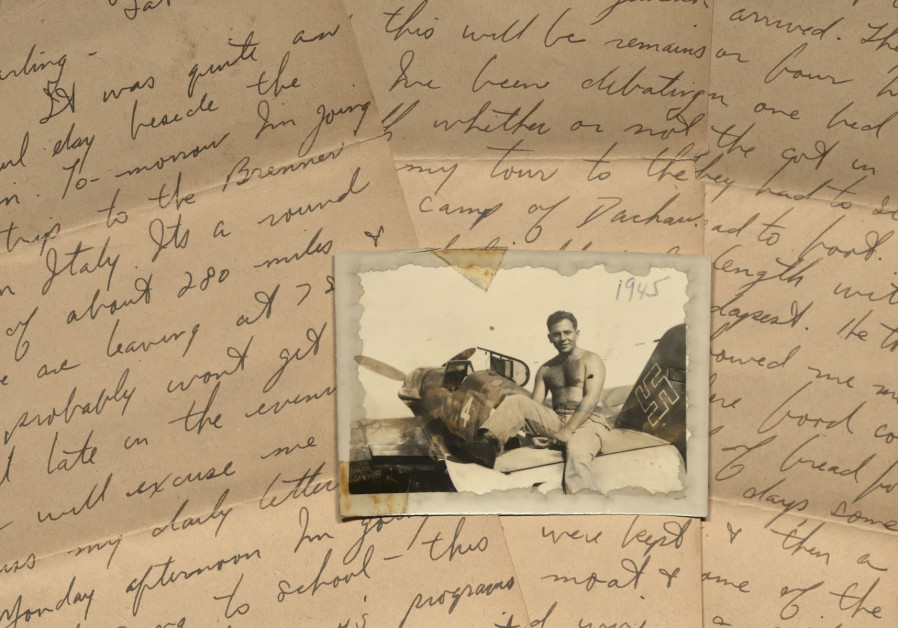

A letter from an American soldier detailing the conditions in Dachau

Seymour Reiss penned a 10-page letter to his wife, Ethel, detailing the horrific conditions in the Dachau concentration camp, which the Army sergeant had visited two months after its liberation in 1945.

“We then went to the kennels where they left the dogs,” wrote Reiss, seen in the small photo. “The dogs were kept hungry + trained to attack these prisoners. I saw the pole + dummy where they would hang the dummy, dressed in the striped suits that the prisoners wore. They would put a raw steak between the legs of the dummy + the dogs would leap for it + tear into it savagely. Paul (the Jewish prisoner) told us that many a stubborn prisoner was tamed by this method.”

A photo of a Jewish woman who perished in Treblinka

Joseph Helfgott, a Polish Jew, kept this photo of his wife, Dwora, with him as he went through the Auschwitz, Mauthausen and Ebensee concentration camps. He frequently rubbed it with his thumb, which accounts for why the photo is so worn. Though Helfgott survived, his wife and their daughter Chana did not.

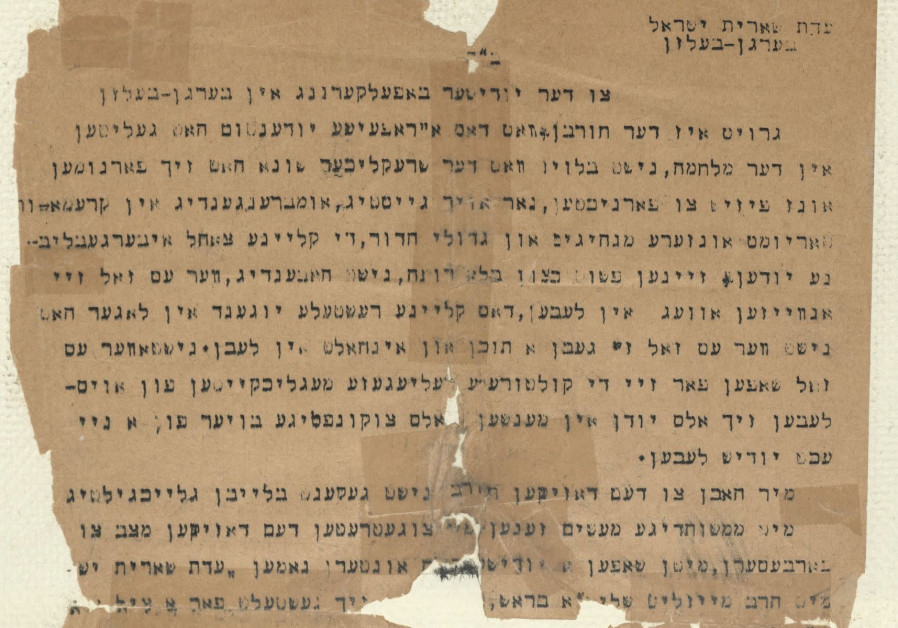

A letter detailing efforts to improve life for Jews in Bergen-Belsen

This letter, written in Yiddish circa 1941 by Holocaust survivors in the Bergen-Belsen displaced persons camp, details their efforts to improve Jewish life there. They wrote that they had organized houses of worship, a special fund for brides, kosher kitchens and slaughterhouses.

The letter goes on to say that much more work is needed and implored the survivors to pitch in for the Jewish community.

It was donated by a niece of Philip Kahan, a U.S. soldier who had emigrated from Romania in the 1930s and lost most of his family in the Holocaust. It is not clear how Kahan got the letter, but he carried it in his wallet until the day he died.

Those who would like to share Holocaust-related artifacts can contact the museum at curator@ushmm.org or (202) 488-2649.