There are all sorts of lessons out there just waiting to be learned from the goings-on of the past couple of years. We won’t get into yes vaccine-no vaccine debates, the efficacy of masks, or the economic and psychological fallout of lockdowns. But one thing, surely, must come shining through the pandemic mist. When we were all grounded, restricted to our immediate vicinity, and not allowed to drive or fly anywhere, the world was a cleaner place, and the air was far less polluted.

That must come into the equation with the approach of Earth Day 2022. This year’s global environmental event takes place on April 22, over half a century after the UN-sanctioned curtain-raiser. Earth Day is now marked all over the globe and, this time around, the theme is “Invest in Our Planet” and features six primary programs: The Great Global Cleanup; Sustainable Fashion; Climate and Environmental Literacy; Canopy Project; Food and Environment; and the Global Earth Challenge.

All are crucial existential issues that need to be tackled by every country. But how are we getting on over here at our end of the Middle East? What progress have we made in cleaning up our act, and what do we have to offer the world?

EVEN THE briefest of glimpses of the OLAM roster suggests the answer to the latter question is plenty.

OLAM is a network of Jewish and Israeli organizations working in the fields of global service, international development, and humanitarian aid. It acts as a sort of hub for a wide range of enterprises getting into all kinds of positive ecological derring-do, both here and all over the world.

OLAM’s declared goals include aiming “to inspire, educate, and empower Jewish leaders to become champions for global service, international development, and humanitarian aid.” And there is looking “to bring together Jewish and Israeli global service, international development, and humanitarian aid practitioners to network, learn, and pursue ethical best practices.”

All of the above sound like a wholesome endeavor clearly designed to improve the lot of one and all, across geographic, cultural and ethnic demarcation lines.

RABBI YONATAN Neril is waste-deep in that helping hand mindset, and there seems to be a “For Torah shall go forth from Zion” line of thought in there, too.

Californian-born Neril is founder and executive director of the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development (ICSD). As a spiritual leader, Neril feeds off religious Jewish sources as the springboard for his organization’s environmental activities. I was intrigued to learn how Neril and his colleagues came up with the idea of marrying biblical content and sensibilities with green pursuits, and how it works.

“I founded the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development almost 12 years ago. We are an Israeli-registered NGO,” he explains. “Our mission is to reveal the connection between religion and ecology, and mobilize people to act.”

Neril says he imbibed that interface from the word go, with the nip and tuck message coming home resoundingly to him in his teen years. “I grew up with both Jewish practice and an environmental connection,” he notes. “I learned about the connection between Judaism and ecology when I went to a Jewish summer camp near Yosemite [National Park in California].”

It is not, he says, a generally understood fusion. “I am aware that most people think that ecology is one thing, and religion is another. Yet Jews may learn about Jewish ecology on Tu Bishvat, or maybe when they read the Torah portion about Noah and the Flood.”

Addressing that misunderstanding forms part of the ICSD credo, with, naturally enough, Neril taking a literary approach to the matter. “For the past 12 years, I have been working to connect the two. One of the ways is through a book I coauthored, together with Rabbi Leo Dee, Eco Bible – An Ecological Commentary on the Torah.

The two-part publication goes through the Five Books of Moses and cites numerous relevant passages in the Torah.

“Together, it’s an ecological commentary on over 400 verses,” Neril adds. “It says, for example, in Genesis, chapter 2, verse 15: ‘And God placed the human beings in the Garden [of Eden] to serve and conserve it.’”

Then again, it seems the ecological sentiment in the Bible may not be all that clear. “That mandate is in contrast to chapter 1, verse 28 [of Genesis], where it says that God said to the people to dominate the life and conquer the earth.”

That, Neril points out, does not mean we can simply lord it over Mother Nature with impunity. “The rabbis of the Talmud understand that the domination it is referring to is more in the sense of dominion and about enlightened stewardship, and therefore it is not about degrading or despoiling God’s creation.”

That is a message Neril, whose numerous areas of work include serving on the Multi-Faith Advisory Council of the UN Interagency Task Force, and the ICSD, has been disseminating across other religious hinterlands, as far and wide as possible.

“In the past nine months my organization collaborated with a Christian pastor in America who developed a monthly Christian preaching guide based on Eco Bible.” They have been passing the good word on. “We distribute this preaching guide to hundreds of Christian clergy, to encourage them to teach and preach on religion and ecology, internationally.”

ICSD BELIEVES religious leaders can play a major role across a range of environmental issues, and is making inroads over here, too. “My organization also has a close relationship, here in Jerusalem, with various institutions, including the Swedish Theological Institute, and also with the FELM Center – [of] the Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Mission.”

Hopefully, by interweaving divine faith with practical, on-the-ground activism to help preserve this precious, fragile planet of ours, the green message will get out there. Mind you, that’s not a given. Just because you have faith in God and observe religious practices, that does not make you immune to ecological misbehavior.

“I took a group tour in nature today from FELM, and we did pick up trash other religious people had left on the trail,” remarks Neril, a vegan who is also concerned with animal welfare, including shechita (Jewish ritual slaughter) and how humane that process is in practice.

ICSD also gets down and dirty with ecological work in the field, primarily in solar energy, which it proffers to communities around Africa. Through its Faith Inspired Renewable Energy Project, for example, in August 2019 the organization facilitated the signing of a memorandum of understanding and land-lease agreement for a commercial-scale solar field on Anglican church lands in Mozambique.

Solar fields, the ICSD website notes, “bring electricity to Africans, reduce indoor air pollution and deforestation, and curb climate change.”

Meanwhile, back here, the environmental awareness pendulum continues to swing.

“I think the current government is doing better than any other Israeli government,” says Neril. “We have an environment minister [Tamar Zandberg] who is actually an environmentalist, which is something of a rarity,” he wryly adds. “And there are a number of very ecologically committed MKs, like Alon Tal.” Tal is a leading environmental activist and founder of Israeli environmental NGOs.

So, there appears to be hope, although Neril believes there is still a long and winding road to be trod.

“Unfortunately ecological awareness is a lower priority here than it needs to be,” Neril states, referencing the limited space on school curricula devoted to green issues. “There is a small amount of environmental education in schools, nowhere near where it should be.”

Naturally, Neril is particularly interested in the religious sector. “The amount of religious environmental education that’s taking place in National-Religious, haredi and Arab, Muslim public school systems is also tiny.”

We could, Neril believes, do a lot more to enlighten people of all religious, ethnic and cultural stripes here about food waste, and about the benefits of striving to achieve national self-sufficiency, and reducing the amount of food imports and their carbon footprint, in the process.

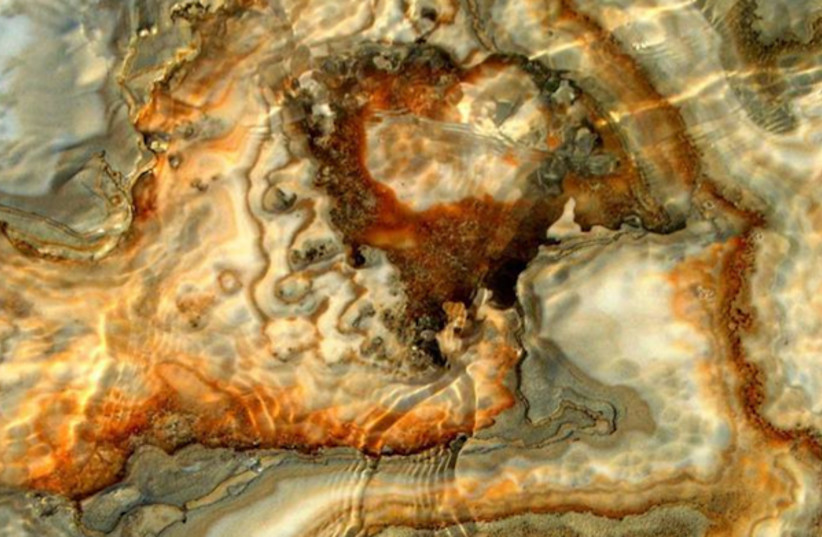

ARI FRUCHTER joins in the chorus for action on the ecological front. Fruchter and Noam Bedein are giving their all to make us more cognizant of the dire condition of the Dead Sea. And, while there is no denying the contribution of evaporation to the rapidly dropping water level there, it is not just down to the regional weather conditions and, indeed, climate change.

“It seems it should be a record year for the Dead Sea,” Fruchter says, referring to the abundance of precipitation in these parts this past winter. “The Kinneret [Sea of Galilee] is blessed with more water than it has ever had before. But nothing is changing at the Dead Sea. No water is being opened up [to flow southward from the Kinneret] to the Dead Sea.

“The Israel Chemical Corporation, they’re pumping water out [of the Dead Sea] for industry.”

ICL conducts mining operations at the Dead Sea to extract minerals such as potash, bromine, sodium and magnesia. Those products are exported around the world.

Fruchter and Bedein have, for some time, been making efforts to get the message out there about developments at the lowest spot on Earth, aiming to slow down the decimation of the body of water and, of course, the ecosystems in the area. To that end, they are working to establish the Dead Sea Museum in Arad, and have uploaded photographs, taken by Bedein, that document the vanishing beauty there.

Fruchter is frustrated by the lack of official action, and by the general public’s malaise and ignorance of the evolving natural disaster. “I am not aware of any positive [state] steps being taken to help the Dead Sea. Most people believe the Dead Sea is where the hotels and factories are [to the south near Ein Bokek]. That is not the Dead Sea. People are unaware of what is happening.”

That said, attempts to raise the region’s public profile by bringing in American photographer Spencer Tunick, who is best known for his mass nude shots, seem to be yielding some dividends.

“Spencer made a presentation to the members of Kibbutz Kalya [at the northern end of the Dead Sea]. That was an eye-opener for them. I think Kalya was established to take care of the Dead Sea, and the members have been living right by its side as the water has been depleted. Spencer’s presentation was a wake-up call for them – if they aren’t going to do anything about the situation, who will?”

Fruchter believes that investment is needed in the actual Dead Sea, in the north, away from the hotel sprawl near Ein Bokek. “I think we are all naive. There is no one out there who doesn’t agree that the place is magical, but we are not aware enough to understand what’s going on.

“Most people want to go to the hotels. But that is not the Dead Sea. That is a reservoir for Dead Sea factories. Why are we not investing in luxury hotels in the real Dead Sea?” That, Fruchter and Bedein believe, could connect the public with the place, enable people to witness the process of the declining sea level and, possibly, galvanize us into action.

LIKE NERIL, Shoshan Haran is in the business of helping out, around the globe, by exporting know-how nurtured and developed here to lesser privileged parts of the world. To that end, a decade ago, she founded Fair Planet.

After gaining a PhD in plant protection from the Hebrew University, she won a Fulbright grant for a postdoctoral fellowship at Rutgers University, New Jersey. She spent 11 years working in research, various areas of technological expertise and intellectual property for Hazera Genetics, an Israeli global leader in the seed industry.

One bright day she felt a change of professional tack was in order, followed by an epiphanous moment when she realized that it was all well and good developing high-quality seeds for agricultural use, but wouldn’t it be a good idea to make them accessible to those who need them most?

“While I was at Hazera, I realized what, basically, anyone should know – that seeds are the basis for food in the world,” says Haran, adding that her light bulb moment went a little further. “The seeds were not getting to the hungry countries.”

It was time for action. “I got to thinking about whether I could do something about that,” she recalls.

If anyone was qualified to take action on that front, it was Haran. “I realized I was in a position whereby I had lots of advantages. I knew many seed companies, and, because I come from a kibbutz [Beeri], I believed – rightly – that the kibbutz would support me in helping farmers from the hungry part of the world.”

She set about getting top-grade seeds to smallholder farmers in Ethiopia and Kenya, and enabling them to improve their yields, break out of the poverty cycle and to actually make a living from agriculture. “I thought that if I can bring those seeds to the farmers and find out what suits their needs, I would be providing them with the most powerful means of enhancing the quality of the food they grow, and also to earn money.” And so, through Fair Planet, that has come to be.

Haran says she fed off knowledge and experience from here, and took a leaf out of the early state’s book. “In the 1950s there was mass aliyah. These were basically people who knew nothing about agriculture. The Agriculture Ministry sent people to the farmers to teach them and show them how to work, in situ. They came to see the conditions and show them what to do in practice.”

Fair Planet also gets locals to spread the word and pass on their recently acquired knowledge further afield. There is a ripple effect going on. “We train between five and 10 farmers in each village, and the other farmers – there are normally around 1,000 farmers in each village – learn from the agriculturalist who is now having success. We also train local Agriculture Ministry instructors based on the methods used in Israel, in the 1950s. Then they take that know-how to villages we don’t access.”

Haran offers some impressive statistics. “There is a very powerful diffusion effect here. We provided training in 65 villages in Ethiopia, to around 2,600 leading farmers, and we trained 150 local instructors. Within five years, that knowledge was passed on to 75,000 farmers all over Ethiopia.”

Yields increased dramatically with the newly acquired know-how and better-quality raw materials, as did income and the farmers’ financial independence.

The general ecological situation back home could also do with a shove in the desired direction. “We have a lot to improve here when I comes to environmental matters,” Haran says, with a nod toward Fruchter and Bedein. “The whole issue of the Dead Sea is catastrophic.”

She says it is very much down to a simple matter of knowing what is going on around us. “People are just not aware of these things.”

She cites an example from very close to home. “It took me a lot of time to realize I had a solution which needed to be offered to the people who need it. We are all only individuals, but we can all do something.”

The next time we place our groceries in a new plastic bag, instead of bringing one from home or using a backpack or reusable bag, or wash our car, perhaps we should bear that personal responsibility ethos in mind, for the good of us all. ■

For more information: olamtogether.org, www.interfaithsustain.com, www.thedeadseamuseum.com, www.fairplanet.ngo

The Environment and Climate Change portal is produced in cooperation with the Goldman Sonnenfeldt School of Sustainability and Climate Change at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. The Jerusalem Post maintains all editorial decisions related to the content.