Admirers of coral reefs, such as those at the southernmost point of Israel, have long thought that deep ones serve as a lifeline for shallow-water reefs, which suffer significant damage from human activities and climate change.

But researchers at Tel Aviv University (TAU) and the Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat have found that the ability of soft coral to reproduce and grow is much weaker where reefs are in deeper waters and not shallow waters. The study suggests that some deep reef coral populations actually depend on shallow-water populations to thrive.

A new Tel Aviv University study, in collaboration with the has found that coral spawning events in the Gulf of Aqaba and Eilat, Red Sea, at the deep end of the focal species’ depth range (~30–45 m) occur at much lower intensities than those at shallow water (0–30 m). The study was recently published in the prominent journal Ecology under the title “Soft coral reproductive phenology along a depth gradient: Can “going deeper” provide a viable refuge?”

It was led by doctoral candidate Ronen Liberman from TAU’s School of Zoology and Dr. Tom Shlesinger from the Florida Institute of Technology; and supervised by Prof. Yehuda Benayahu of TAU’s School of Zoology and Steinhardt Museum of Natural History. Prof. Yossi Loya, also of the zoology school and Steinhardt Museum, participated in the study as well.

Can deep reefs serve as a “lifeline?”

The team proved that while in shallow water about half of the corals engaged in each reproductive event, this proportion dropped to only 10% to 20% in the deeper part of the reef. The significance of their finding is that there is an insufficient basis for the prevalent hope that deep reefs can serve as a “lifeline” for degraded shallow reefs.

In fact, the team of researchers suggested that for some coral species, the opposite is true – to survive over time, deeper coral populations may more often rely on shallow-reef coral rather than the opposite. The study also showed that sharp rises in water temperature within a day or two affected the onset of the breeding events in the species that was studied.

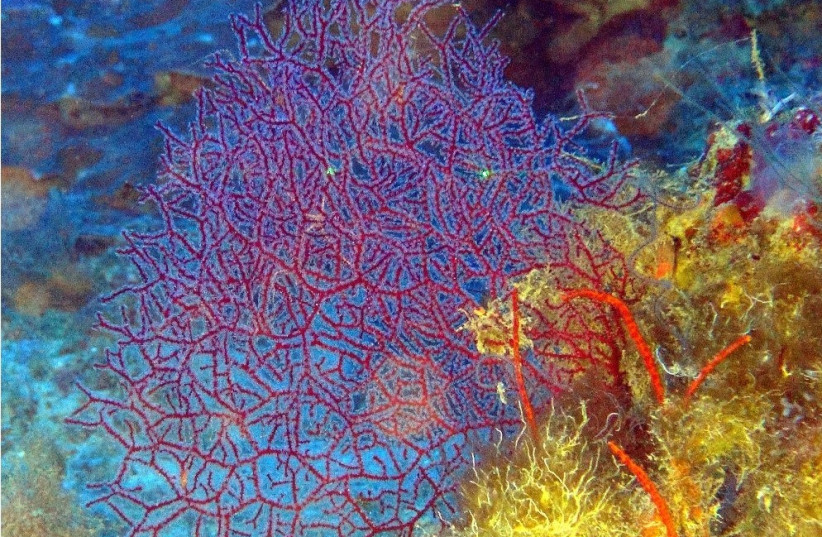

Conducted over five years including five breeding seasons, examined the reproduction of soft corals – also called “Octocorallia” – some of which live throughout a wide depth range in the Gulf of Aqaba and Eilat. They are a class of marine invertebrates that includes the sea anemones, stony corals and soft corals. Adult specimens are almost all attached to the seabed, while their larvae can disperse as part of the plankton.

The uniqueness of the study lies within the long-term and intensive examination of coral reproduction throughout a wide depth gradient spanning up to 50 meters. The researchers focused on a species of soft coral called Rhytisma fulvum that reproduces by “surface-brooding” – a reproductive mode by which the coral hatch their strikingly yellow larvae glued externally to the coral surface for several days. This unique reproductive mode helps scientists overcome many of the difficulties in examining and monitoring coral reproductive events, especially in the more challenging-to-work depths.

“Most coral species are hermaphrodites, meaning that each individual functions as both male and female, and they reproduce by brief and synchronous spawning events, which usually occur once a year in the summer months,” explained Liberman.

“During this synchronized event, many corals simultaneously release a huge amount of sperm and eggs which meet externally in the water, where they undergo fertilization and form embryos. In other species, male corals release sperm into the water, and these cells migrate into female corals and fertilize the eggs internally so that fertilization and embryonic development occur within the coral.”

In both cases, this takes only a few minutes, mostly at night, so it is very difficult for researchers to watch and capture the moment, especially at great depths where divers cannot remain for a long time. Therefore, very little is known about coral reproduction at depths greater than approximately 15 meters.

The researchers focused on the soft coral Rhytisma fulvum, which lives in the Gulf of Eilat and Aqaba along a large depth range – from reef flats close to the sea surface and down to 50 meters. They chose this species because of its unique reproductive strategy called “surface-brooding” that begins when male colonies release sperm cells in a synchronized manner. They later reach female colonies where internal fertilization occurs.

Unlike other coral species, however, in this species embryos do not go on to develop internally within the coral. Instead, the fertilized eggs are released and cling to the colony via mucus for six days, where they develop into larvae. “The developing embryos have such a vibrant yellow color that makes it a very colorful event, lasting for several days. Thanks to that fact, we were able to monitor rather easily a large number of colonies along a large depth range throughout five annual reproductive seasons,” noted Ronen.

The researchers dove to various depths, positioned temperature sensors and examined several characteristics of the breeding events including timing, duration and intensity of the events. They aimed at understanding which environmental factors influence the onset of reproductive events. The study showed that the timing and synchronization of reproduction events at any given depth are connected to a clear and fast increase in water temperature of one to 1.5 degrees Celsius within 24 to 48 hours – a kind of a “heat wave” that is typical in the waters of the Gulf of Aqaba and Eilat in early summer.

In shallow water of only five to 15 meters deep, the reproductive events always occurred days to weeks before they were observed at the greater depths. The researchers said this phenomenon is due to the short-term heat waves in the deeper water that usually occurred only several days to weeks after they occurred in the shallow water.

The reproductive intensity was measured by the number of colonies that reproduced and released embryos at each event. “We found that the number of colonies releasing embryos was significantly smaller at a depth greater than 30 meters,” Ronen added. “Whereas at a shallow depth, about half of the colonies participated in each spawning event, in the deeper water the participation rate dropped to only 10% to 20%.”

In light of these findings, the researchers believe that the deep-water coral populations are less likely to thrive on their own and are reliant to some extent on populations from the shallower reef. Because of their lower breeding intensity, it appears that the deep-water coral population requires the contribution of the larvae from the corals found in the shallower water. The researchers suggest that this “weakness” among the deep corals may be linked to the much lower intensity of sunlight that reaches their habitat; sunlight is necessary for photosynthesis in which symbiotic algae found within the coral tissue convert light energy to provide the coral host with the chemical energy it needs.

The researchers concluded that “today, when coral reefs around the world are being severely damaged by climate change and other human impacts, many are pinning their hopes on deeper reefs to provide a ‘lifeline’ of support for shallow-water coral reefs that may be more exposed to some hazards. While we do not wish to diminish the optimism, our research suggests that this hope might have been overestimated. Instead, it looks like it’s the deeper coral populations that need the shallow ones to persist more than vice versa. Therefore, these hidden deep reefs require attention and protection in their own right, perhaps even more than the shallow reefs.”

The Environment and Climate Change portal is produced in cooperation with the Goldman Sonnenfeldt School of Sustainability and Climate Change at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. The Jerusalem Post maintains all editorial decisions related to the content.