New research conducted by scientists in the United Kingdom suggests that extreme heat could potentially lead to the extinction of humans and nearly all other mammals in approximately 250 million years, which is earlier than previously anticipated by other models.

This event would mark the first mass extinction of a magnitude comparable to the era of the dinosaurs.

A team of researchers, led by scientists from the University of Bristol, published their findings in Nature Geoscience on Monday.

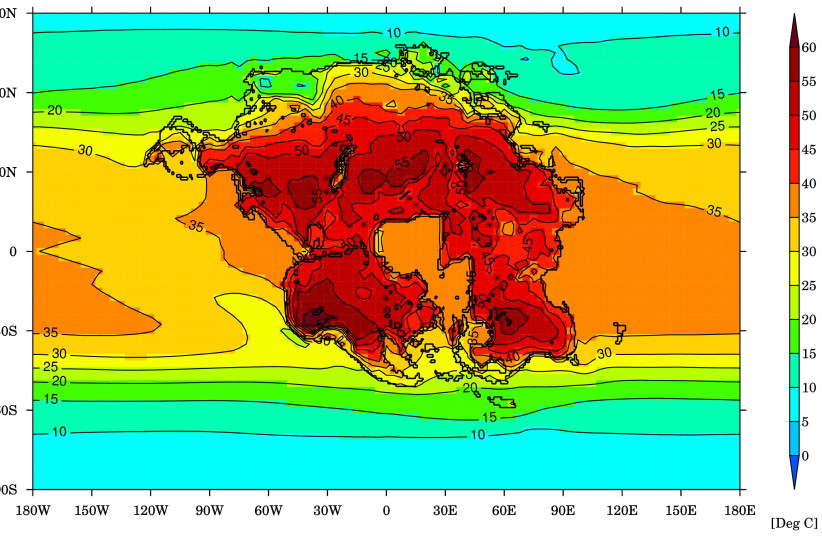

They employed advanced supercomputer climate models to illustrate the escalation of climate extremes that will occur when the Earth’s continents eventually amalgamate into a scorching, arid landmass, referred to as “Pangea Ultima.”

“Mammals have dominated Earth for approximately 55 million years thanks to their adaptations and resilience to warming and cooling,” the authors wrote, explaining that it was always understood that all life would eventually perish in a “runaway greenhouse once absorbed solar radiation exceeds the emission of thermal radiation in several billions of years.”

However, they continued, the planet may become inhospitable to mammals much sooner “because of long-term processes linked to plate tectonics.”

“In some 250 million years, all continents will converge to form Earth’s next supercontinent, Pangea Ultima,” they wrote.

This supercontinent would predominantly occupy the hot and humid tropical regions, potentially subjecting a significant portion of the planet to temperatures ranging from 40 to 70° C.

The geological processes responsible for forming the supercontinent would also increase the frequency of volcanic eruptions. These eruptions, in turn, would release substantial amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, exacerbating the planet’s warming.

Furthermore, concurrently, these elevated temperatures are poised to intensify as the sun grows brighter, emitting more energy and, consequently, raising the Earth’s temperature.

“Every 100 million years, the sun gets about 1% brighter and emits about 1% more energy than it currently does,” explained lead author Dr. Alexander Farnsworth in a phone interview with The Jerusalem Post.

Farnsworth, a senior research associate at the University of Bristol, said that in about 250 million years, the sun will be about 2.5% brighter and emit 2.5% more radiation than today.

“The newly-emerged supercontinent would effectively create a triple whammy, comprising the continentality effect, hotter sun, and more CO2 in the atmosphere, of increasing heat for much of the planet,” said Farnsworth. “The result is a primarily hostile environment devoid of food and water sources for mammals.

“Widespread temperatures of between 40 to 50 degrees Celsius and even greater daily extremes, compounded by high humidity levels, would ultimately seal our fate,” he continued. “Humans – along with many other species – would expire due to their inability to shed this heat through sweat, cooling their bodies.”

Throughout history, mammals, including humans, have endured and thrived by exhibiting remarkable adaptability to various weather extremes, the university explained. This adaptability has been exemplified through evolutionary traits such as fur for cold climates, the practice of hibernation during cold spells, and brief periods of warm weather hibernation.

However, the university explained that while mammals have evolved mechanisms to enhance their survivability in colder conditions by lowering their temperature tolerance, their capacity to endure higher temperatures has generally remained unchanged. Consequently, prolonged exposure to extreme heat becomes significantly more challenging to cope with, and if the climate simulations materialize, it would ultimately render survival unattainable.

The scientists used climate models to arrive at these predictions, simulating temperature, wind, rain, and humidity trends for Pangea Ultima. Farnsworth told the Post the models were similar to the ones that meteorologists use to predict the weather in the next six, 12, or 24 hours.

To project future levels of CO2, the research team employed models that considered tectonic plate movements, oceanic chemistry, and biological processes, accounting for the inflow and outflow of carbon dioxide.

Farnsworth pointed out that these CO2 levels are also connected to the scale of greenhouse gas emissions from human activities. Nevertheless, he emphasized that even considering human-induced damage, the planet is expected to remain habitable until this shift in seismic landmass occurs. At that point, it is projected that only a fraction, ranging between 8% and 16%, of the land will remain habitable for mammals.

“We think CO2 could rise from around 400 parts per million (ppm) today to more than 600 ppm many millions of years in the future,” said Prof. Benjamin Mills of the University of Leeds, who led the future CO2 calculations. “Of course, this assumes that humans will stop burning fossil fuels. Otherwise, we will see those numbers much, much sooner.”

Climate-tech innovation

According to Farnsworth, one of the few viable solutions would involve the development of human-made technologies, including structures or enclosures capable of protecting people from extreme outdoor temperatures. Nevertheless, he said addressing this challenge would necessitate innovations to sustain food sources, as livestock and crops would struggle to survive in such conditions. Ensuring water security would pose yet another formidable challenge.

“We would need to engineer the climate to cool it down, maybe by reducing CO2 or trying to block off some of the radiation from the sun,” Farnsworth offered. “But even then, the rest of the species would have to live in this natural climate, which would mean mass extinction.”

Another takeaway from the research is the need to understand the role of tectonics and continental layouts when researching exoplanets planets beyond our solar system.

Recently, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has made measurements indicating the presence of water vapor and oxygen on certain exoplanets, raising the possibility of their habitability. However, Farnsworth emphasized that our own solar system’s habitability depends on the complex dynamics of tectonics, as highlighted in his research.

“This work also highlights that a world within the so-called ‘habitable zone’ of a solar system may not be the most hospitable for humans depending on whether the continents are dispersed, as we have today, or in one large supercontinent,” Farnsworth said.

The Environment and Climate Change portal is produced in cooperation with the Goldman Sonnenfeldt School of Sustainability and Climate Change at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. The Jerusalem Post maintains all editorial decisions related to the content.