Genius is so difficult to define. We can see it but often can’t put a finger on its essence. Maybe because only a few are blessed, or cursed, to possess it.

Catalonia, or Catalunya as the locals write it, is the restive, independence-oriented region of northeastern Spain, centered on Barcelona. Visitors to Barcelona will be familiar with the brilliance of Antoni Gaudi in the form of Sagrada Familia, Casa Mila and Casa Batllo.

But the Agencia Catalana de Turisme hopes visitors will take time to marvel at the rest of this fascinating region. This year, the organization launched The Grand Tour of Catalonia – a 1,931-k.m. route that takes in landscapes, culture, gastronomy, architecture and more.

Section five of the route includes visits to the homes of two of Catalonia’s geniuses, the Figueres of Salvador Dali and the Girona of Nahmanides.

While the Grand Tour is aimed at road users, we used the region’s excellent train service. Local services offer a lazy journey through the countryside and small villages and towns, while the express trains reach destinations in a blur.

For the tourist, Figueres is Dali. With a population of some 50,000, the town is compact. Two train stations serve the town. It’s around a 20-minute walk from both to Theatre Museu Gala Salvador Dalí, the second-most visited museum in Spain, after the Prado, Spain’s national art musem.

A couple of worthwhile stops en route to the museum are the town’s toy museum that includes Dali’s childhood teddy bear and the fine-dining experience at the Hotel Duran, where Dali went to dine, drink and think.

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol, was born in Figueres in 1904. He was a misfit. People didn’t get him, including his father. Even the surrealists of the 1930s found him too outlandish.

A group of surrealists had gathered in 1936 London to launch a new exhibition. Dylan Thomas was there serving up boiled string to the celebrity guests.

A few weeks earlier, Dali purchased a diving suit for the event. The store owner asked him where he intended diving, to which he supposedly replied, “Into the subconscious of the human mind.”

He marched into the exhibition wearing the suit and holding a pool cue in one hand and two dog leashes in the other. Not long after, he began what looked to those gathered like the dance of a madman. Only his wife, Gala, knew something was awry. In his excitement, Dali had completely forgotten to attach the oxygen tank to his suit and was asphyxiating.

The diving suit greets you on the facade of the museum alongside classical statues more befitting of the building that was once the town theater.

Once inside, no matter where you look, you will be met by images and creations that will challenge your right-mindedness. Guide Maria Rizzolo says Dali has changed the way she thinks. She often finds answers in empty spaces rather in the places where matter dominates.

Dali's work

DALI’S WORKS are innumerous, each seems more brilliant than the last. Perhaps the easiest to understand are the works that comprise a collection of Jewish/Israeli paintings he created to mark the 20th anniversary of the creation of Israel. You can find them on the second floor of the museum. You may be familiar with the menorah just outside arrivals at Ben-Gurion Airport, in Tel Aviv. It is based on one of Dali’s paintings in the collection.

His body of work is not just restricted to canvas, abstract and surrealist, but sculptures, house decoration, optical illusions and even a motor vehicle that rains on the inside.

Dali was brilliant, a clown, arguably a sexual deviant, entertainer, isolationist and so much more. The museum is a wonderful journey through his life and a chance for some unusual introspection for visitors. Do use the services of a guide. It will make the trip even more memorable.

From Figueres, it’s just a 20-minute high-speed train ride to Girona, one of the pearls of both Catalonia and of Jewish Spain.

The old city is hilly but that means superb photo-ops of the ancient streets and magnificent views of the surroundings, all the way to the snow-covered Pyrenees. You can walk on both the original Roman and Medieval walls before or after a tour of the old town – the walls take you back into the modern city.

The cathedral dominates. It contains the second-largest nave in Christendom. A tiny synagogue predated the cathedral on the same spot. With time, the Jewish community opened another synagogue, which today is a part of the Jewish Museum complex. Much of the Jewish Quarter or El Call in Catalan (pronounced to rhyme with bye) is intact. There are several indentations in doorways where mezuzahs were once mounted. A sign points the way to a mikveh but our tour guide maintains it was probably never used as a Jewish ritual bath.

However, in the museum there is an original mikveh below ground in a square dominated by a wonderous art piece created by Israeli Frank Meisler. It shows how so many Jews, including religious scholars, forged inventions that helped Christopher Columbus discover the New World.

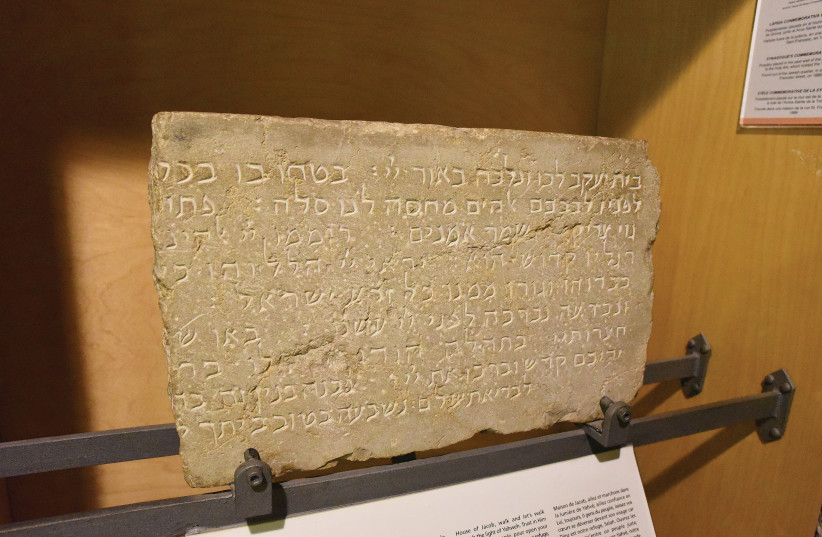

The museum includes easy-to-read gravestones moved from the ancient Jewish cemetery just outside the old town.

But pride of place in the collection goes to a seal that belonged to Bonastruc ça Porta, also known as Rabbi Moshe Ben Nahman, or Nahmanides, or Ramban. The Hebrew inscription reads “Moses, son of Rabbi Nahman, from Girona, have courage.”

Nahmanides spent his final years in Israel, erecting what is today the second-oldest synagogue in Jerusalem – the Ramban synagogue in the old city. But he is famed for his work in Catalonia as a rabbi, prolific author, kabbalist, disputant and doctor. He is seen as one of the progenitors of the Kabbalah.

Before his departure for Israel, Nahmanides participated in one of the most infamous of disputations, in which the Church challenged the very ethos of Judaism. In 1263, he and his interlocutor stood before the king in Barcelona and the two discussed whether the Messiah had appeared, whether the Messiah announced by the Prophets was to be considered as divine or as a man born of human parents and whether the Jews or the Christians were in possession of the true faith. The king recognized the justness of Nahmanides’ arguments but nonetheless he was exiled, eventually finding his way to Israel.

The museum is not only a tribute to Nahmanides and the other Catalonian rabbis of his day but also sheds light on both the daily life of the Jews of Girona and the tremendous contributions of the community to the scientific and artistic development of medieval Europe.

The writers were guests of Agencia Catalana de Turisme. They host ‘The Jerusalem Post’ Podcast – Travel Edition jpost.com/podcast/travel-edition. For more information about the Grand Tour, visit: https://grandtour.catalunya.com/en.