CHICAGO — It was 6 p.m. Monday night and the hallway of the Chicago hotel was suddenly filled with Israelis navigating suitcases through a throng of American Jews debating what to eat for dinner.

They were headed to the airport for the last flight to Israel that would allow them to vote in Tuesday’s election there, the fifth in less than four years. Israel does not allow absentee voting, except for people living abroad on behalf of the government, and despite their election fatigue, they didn’t want to sit out a contest that could dramatically change their country’s direction.

Ultimately, they wouldn’t make it home. The direct flight from O’Hare International Airport to Tel Aviv was canceled, Jerusalem Post reporter Zvika Klein tweeted Monday night, because of a broken toilet.

Still, their single-minded focus — and the applause they received from the Americans who sent them off — reflected the election anxiety that has been laced through the convening here by the Jewish Federations of North America, the umbrella group for local Jewish charitable organizations. With US elections that could flip control of the Senate set for next week, it was Israel’s contest that has preoccupied the 1,300 influencers, executives and lay leaders who have gathered for the group’s first major in-person conference since 2018.

Many of them will have to contend with the impact of the election on the communities they serve. Already, how to direct funding toward Israel issues and how to navigate growing criticism of the Israeli government have been vexing questions for local federation leaders. A far-right government helmed by longtime prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, whose values are at odds in many ways with those of most American Jews, could make the situation more complicated.

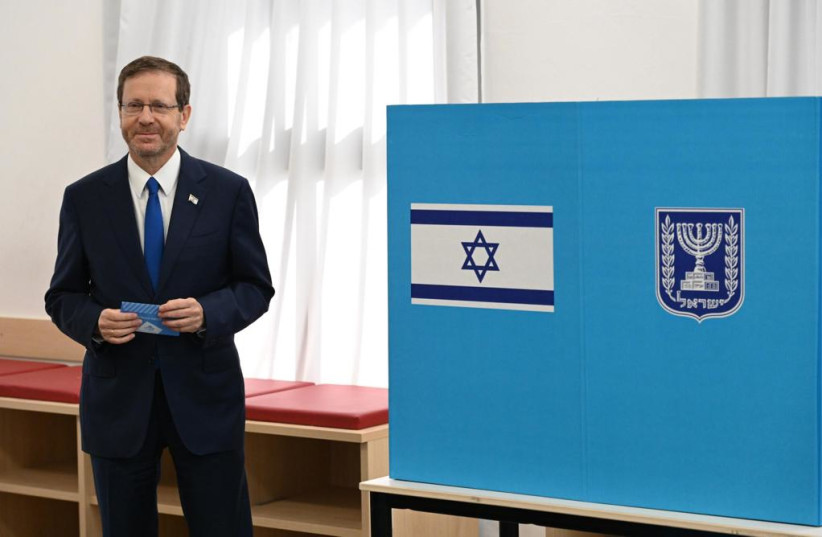

“I am aware of the questions posed in many Jewish communities around the world about the outcome of the elections. The results may or may not be to your liking, but the vote of the Israeli people should be respected.”

Israeli President Isaac Herzog

“I am aware of the questions posed in many Jewish communities around the world about the outcome of the elections,” Israeli president Isaac Herzog said in a prerecorded message to conference attendees. “The results may or may not be to your liking, but the vote of the Israeli people should be respected.”

US Jews fear Itamar Ben-Gvir ascending to the government

Like many major Jewish organizations in the United States, few at the convention would speak on the record about the election and the live potential for it to install into the government Itamar Ben-Gvir, a right-wing provocateur whose rise has been the surprise story of this election cycle. But in hallway conversations and at the hotel bar, many said they were alarmed by Israel’s rightward lurch and by the seeming embrace by voters of all ages of Ben-Gvir’s anti-Arab activism.

For federation leaders, the election results could present practical challenges. Will local Jews choose to donate to support a country whose leadership is abhorrent to them? It’s one thing to organize trips to Israel to demonstrate support when the country’s enemies are antagonizing it; what about if the impetus for violence comes from Jews?

Many local leaders said they had been thinking about what they would do after the election results are clear, whenever that is.

“There’s a conversation about Tuesday night, and a conversation about Wednesday, and a conversation about 44 days after that,” said Jeremy Burton, who heads the Jewish Community Relations Council of Greater Boston, “and there are distinctions among them.”

Burton was referring to the complicated and volatile post-election process to form a government. The candidate who wins a majority of seats in Israel’s parliament on Tuesday, 61 or more, would almost certainly be given the green light to form a governing coalition — and he would have 45 days to do so. If Netanyahu meets that threshold, as polls suggest he could, the 45-day window is when his handshake deal with Ben-Gvir would formalize Ben-Gvir’s role in the new government — or become the newest addition to a long history of alliance promises that Netanyahu has reneged upon when better political options present themselves.

A broken promise by Netanyahu is a best-case scenario, according to many people at the conference who would speak only off the record. They say that if Benny Gantz, the defense minister who is running as the leader of the Blue and White party, exceeds the tally by Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich, who are running together in the Religious Zionism alliance, they would expect Netanyahu to drop the extremists and instead create a more centrist government that would be palatable to American Jews.

Another desired outcome: a continued stalemate, in which no candidate gets a mandate to form a government. In that scenario, Yair Lapid, the centrist current prime minister, would continue to run the country.

“The longer he is in charge, the more people will believe that he can be in charge,” said one leader of an American Jewish organization who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

That’s also the best-case scenario for the Biden administration, according to people at the conference who are in touch with the White House. They said there are live discussions about how the administration would handle Ben-Gvir’s presence in an Israeli government and that a continued caretaker government would be preferable.

Even a panel discussion about Israel’s elections offered little in the way of open discussion. Its moderator, Miryam Rozensweig, the president and CEO of the Milwaukee Jewish Federation, said she and her colleagues expect to hear from local donors no matter the outcome. In the past, she said, she has had people say they would not give to the federation if Netanyahu was elected, in order to send a message; others said the opposite, that they would stop donating if Netanyahu, who is being prosecuted on corruption charges, remained in power.

Asaf Zamir, Israel’s consul general in New York, declined to answer question after question about the possible outcomes. Appointed to a three-year term by Naftali Bennett, Lapid’s predecessor, Zamir is charged with being a mouthpiece for the Israeli government to Americans.

“I’m in the only part of my life where I can’t give you the real answer that I think,” he told moderator Yaron Dekel, a longtime Israeli journalist who is now an official emissary for the Israeli government working in Canada.

Instead, Zamir challenged Dekel to offer his own predictions. Dekel said he thought turnout would be high and believed that Netanyahu would strongly prefer to work with Gantz — ”but he might not be able to get Gantz so he will take Ben-Gvir against his own will.”

Zamir did offer that he thought a 60/60 split would result in a party crossing the aisle to form an alliance, in order to avoid a sixth round of elections. From which side? “That I don’t want to say,” he said.

Afterwards, in the hall, Steve Rabinowitz, who represents multiple Jewish organizations in the media, bellowed to Zamir, “Why did you go to that panel if you weren’t going to say anything?”

Zamir shouted back, “It was a mistake!”

One person who did speak freely during the panel was Dani Duek, a student at Tel Aviv University who was at the conference because of her role on Hillel International’s student cabinet. Duek rose to ask a question and quickly had the spotlight turn to her.

She said she was distressed by the idea of seeing Ben-Gvir in government but understood why so many others were not. “People like the idea of this simple easy answer, more than thinking Ben-Gvir is someone I would sit down for a beer with,” she said.

Presented after the panel with some of the scenarios that American Jewish leaders are hoping for, Duek said she was not optimistic that any would come to pass. She knows an array of young people voting for Ben-Gvir, including friends from growing up in Kfar Saba and her university classmates.

“I’m not as confident,” she said. “If I let my thoughts go where they want I would cry.”

Among Duek’s concerns about a government that includes far-right parties is the status of women. And late Monday night, at a reception hosted by JQ International on behalf of LGBTQ Jews, attendees were fretting about what would happen to queer Israelis if the government includes openly anti-LGBTQ parties.

“Our lives are in play in these elections,” said Ethan Felson, executive director of A Wider Bridge, a group that advocates for LGBTQ Jews in the United States and Israel. He was referring to the contests in both countries. “We may very well be waking up to these nightmares.”