Is Life a boon?

If so, it must befall

That Death, whene’er he call

Must call too soon.

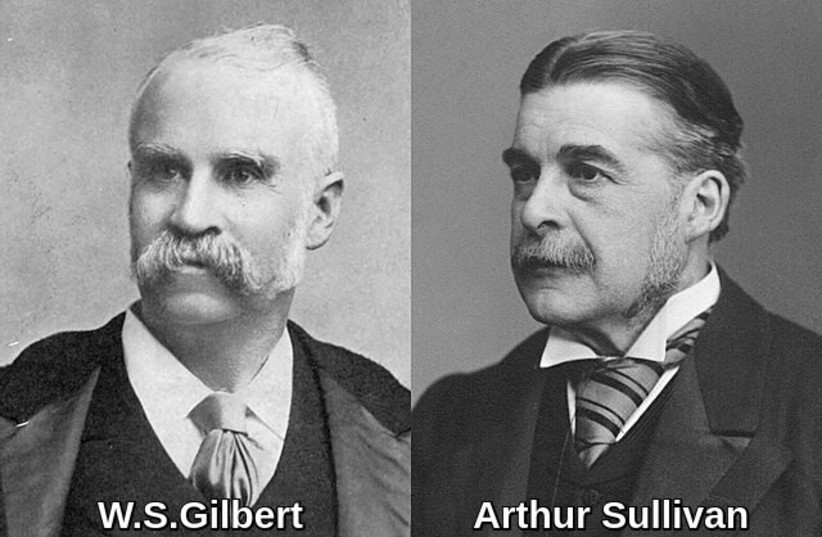

These words are inscribed on a bronze bust that adorns the Victoria Embankment gardens in the heart of London. The memorial, which includes a sobbing woman representing the Muse of music, is to Sir Arthur Sullivan, the eminent 19th-century composer, who formed one of the most enduring partnerships in musical history with playwright and poet W.S. Gilbert.

The words are by Gilbert himself, and are taken from the most serious of the operettas the two wrote together, The Yeomen of the Guard – the only piece where a leading character collapses at the final curtain, either dead or overcome by grief, according to how the audience views it.

William Schwenck Gilbert was a prolific and very successful playwright in mid-Victorian England. Arthur Sullivan had achieved great fame as a composer of classical music. They were introduced to each other in 1869, and agreed to collaborate on a light musical piece of theater, which Gilbert called Thespis, or The Gods Grown Old.

The first night of this very first comic opera by Gilbert and Sullivan took place on December 23, 1871. So December 23 this year marks the 150th anniversary of this auspicious event.

The anniversary is of great significance, even though history records that Thespis closed after just 64 performances, and that this first collaborative effort was so unimportant in Sullivan’s eyes that he did not even keep a copy of the score. It has been lost. All that survives are three musical passages, one of them the chorus “Climbing over rocky mountains,” which Gilbert transposed into a later comic opera, The Pirates of Penzance.

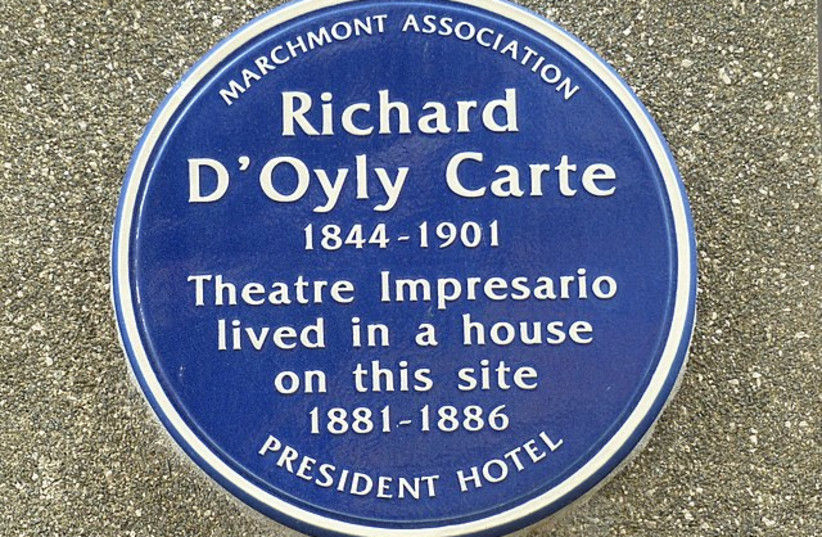

When the run of Thespis ended, Gilbert and Sullivan went their separate ways. It was to be four years before an enterprising musical impresario, Richard D’Oyly Carte, brought them together again.

Carte was mounting a production of Offenbach’s operetta La Perichole, which, by itself, did not provide a full evening’s entertainment. He needed a “filler,” and he asked Gilbert for a one-act piece that Sullivan could set to music. The result was Trial by Jury, a musical delight that was first performed on March 25, 1875. It was wildly successful and quickly became the main attraction. Audiences flocked to the Royalty Theater in London not for the Offenbach, but for the latest theatrical sensation.

Trial by Jury takes place in a topsy-turvy courtroom, in which a young Lothario is being sued for breach of promise of marriage. The judge starts the proceedings by explaining how he had reached his high position. As a penniless young lawyer, he’d needed a push up the ladder, so he decided to marry “a rich attorney’s elderly, ugly daughter.” The rich attorney, delighted at getting her off his hands, had assured him that “she could very well pass for 43 in the dusk with the light behind her.” The judge confides that, when it suited him, he’d thrown her over, “and now, if you please, I’m ready to try this breach of promise of marriage.”

When the jilted bride-to-be appears in court, dressed in her wedding gown and accompanied by her bridesmaids, she wins the hearts of the judge and all 12 jurymen. They are quite unmoved by the defendant’s claim that it is quite in keeping with the laws of nature to “love this young lady today, and love that young lady tomorrow. Nor,” he continues, appealing to their common sense, “is it the act of a sinner, when breakfast is taken away, to turn your attention to dinner.”

The case collapses when the judge decides to marry the young lady himself.

Carte immediately appreciated the cultural potential of a working collaboration between Gilbert and Sullivan and – just as important – the business potential. He commissioned a full-length comic opera from them and formed his Comedy Opera Company to produce it. So was born the three-man partnership that was to create a fabulously successful theatrical phenomenon on both sides of the Atlantic.

The Sorcerer, which ran for 178 performances, was considered a success, and encouraged the partnership to proceed to a new piece.

HMS Pinafore opened at the Opera Comique in London on May 25, 1878, and ran for 571 performances. It became an international sensation.

In the absence of any copyright agreements between the UK and the US, the opera was pirated widely in America. When Gilbert and Sullivan hastened over the Atlantic to produce their “authorized version” on Broadway, they found no less than 42 companies performing versions of HMS Pinafore across the States.

In Pinafore another high-ranking official – in this case the First Lord of the Admiralty – explains how he reached his eminent position despite knowing nothing about the navy and never having been to sea. Sir Joseph Porter’s sung explanation was greeted with delight by a public keenly aware that Britain’s prime minister had recently appointed just such an individual to just this position.

Sir Joseph confides that he began his ascent to high office as an office boy, but eventually, gaining some legal knowledge, he had passed his examination, and was taken into partnership.

And that junior partnership, I ween

Was the only ship that I ever had seen.

But that kind of ship so suited me

That now I am the ruler of the Queen’s Navy.

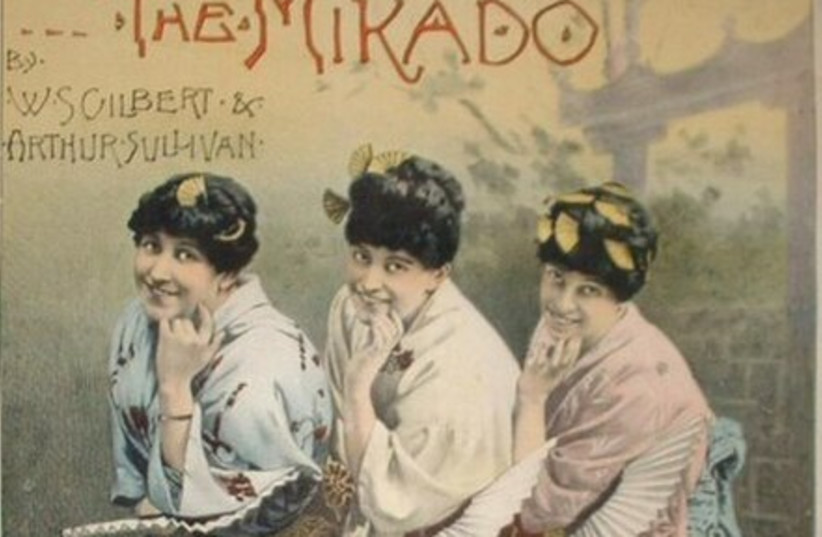

Pinafore’s extraordinary popularity in Britain, America and elsewhere was followed by 10 further Gilbert and Sullivan works. The outstanding piece in later years was The Mikado, which ran for 672 performances in the new Savoy Theater, constructed in the heart of London’s West End by Carte especially to house the G&S comic operas.

Set in Japan, but essentially a satire on Victorian England, The Mikado marked the high-water mark of the G&S collaboration. In a song that became famous the world over, the Mikado confides that his “object all sublime,” which he reckoned he could achieve “in time,” was to “make the punishment fit the crime.” The crimes he lists – various annoyances common in middle-class English society – extracted roars of delighted recognition from the audience.

In all, 14 works resulted from the G&S collaboration. With the exception of Thespis, which is lost (although various attempts at reconstituting it have been tried, using the surviving musical fragments), all have defied the passage of time, and continue to be performed.

G&S companies – professional, semiprofessional and amateur – flourish across the English-speaking world, and not only there. The operettas have been translated into scores of languages, including Hebrew and Yiddish.

THE GILBERT and Sullivan Yiddish Light Opera Company was founded in New York in 1983, although it had its origins 30 years before.

In its productions the characters speak a mixture of Yiddish and English. In HMS Pinafore Sir Joseph Porter becomes “Reb Yosi Yitzhak Nimitzbaum.” The song “He is an Englishman” that features prominently in the piece becomes “Er iz a Guter Yid” (He’s a good Jew). The company has produced recordings of its Yiddish productions of The Mikado, HMS Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance – the last under the title of Di Yam Gazlonim (Thieves of the Sea).

Coincidentally, it was also in 1983 that Robert Binder founded the Jerusalem Gilbert and Sullivan Society and affiliated it to the official London-based G&S Society. He was building on the pioneer G&S enterprise, the Light Opera Group of the Negev (LOGON), based in Beersheba. LOGON had begun mounting G&S operetta productions throughout Israel in 1981, including performances to sold-out houses in Jerusalem. LOGON remains a flourishing theatrical company. With an interesting history and in slightly new guise, the Jerusalem G&S Society also remains a thriving Israeli theatrical enterprise.

In those early days the Jerusalem G&S Society consisted of a handful of enthusiasts who met in each other’s homes to listen to G&S recordings, and who mounted an occasional performance, or a modest, sometimes truncated production. It was only when Paul Salter, a G&S aficionado, arrived from England on aliyah in 2000 that the society took wing. It soon formed a theatrical company to stage the comic operas.

The company devised a musical biography of Gilbert and Sullivan that they performed at the Khan, Jerusalem, under the auspices of JEST (the long-established Jerusalem English Speaking Theater), and then took this to the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival in Buxton, England – an annual event that attracts performing companies and audiences from around the world.

On its return to Israel the company decided to present a full-length, fully staged version of The Mikado with 30 performers, at the newly opened Hirsch Theater, Beit Shmuel. It originally scheduled four performances, but demand for tickets was so great it extended the run.

So began an annual G&S production as part of JEST’s season. The Mikado was followed by The Pirates of Penzance, Iolanthe, HMS Pinafore and Patience. All were performed in English at first, but one of the company’s volunteers, Reuven Ben-Shalom, started translating the librettos into Hebrew. His work forms the basis of the supertitles that are now projected above the stage at each performance.

The Gilbert and Sullivan operas, though assuredly rooted in Victorian England, have proved themselves timeless. Well over a century after they were first performed, they continue to be admired – perhaps even adored – by performers and audiences across the globe.

A website run by the Gilbert and Sullivan Light Opera Company of Long Island lists more than 200 theatrical companies performing G&S operettas around the world. Its list, it says, “is lengthy, though doubtless far from complete.”

Anyone who can access YouTube these days has the complete G&S canon available to them, each operetta performed on TV, on stage or on recordings. There is a wide choice of theatrical companies, professional and amateur, to choose from. A few productions include subtitles, but to enjoy those that do not, either summon up the libretto on a tablet, or acquire one of the volumes containing the complete G&S librettos. With book or tablet on your lap, you can appreciate Gilbert’s wit and his literary skill to the full.

I remember my delight as a teenager in seeing the comic operas for the first time. Back in the mid-20th century the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company used to run repertory seasons at the old Sadler’s Wells Theater in London, since rebuilt. Week after week I’d make my way there to see a new opera and to delight in the performances of Martyn Green, Peter Pratt, Darrell Fancourt and the rest of the G&S stalwarts, the orchestra under the baton of Isidore Godfrey. Their performances are preserved on recordings made in their heyday.

Whether you are so versed in the G&S canon that you can repeat the dialogue with the performers, or whether you await the inestimable joy of coming to the comic operas for the first time, Gilbert and Sullivan retain their appeal. They are here to stay. It is highly appropriate that we take a moment to celebrate the 150th anniversary of their very first collaboration.