It was a dark night. The force descended the slope and approached their objective. They had already caught a glimpse of the operation’s target, the A’Ziv (Achziv) Bridge —but just as they spotted it, they too were detected and immediately fired upon. An incoming bullet apparently set off the explosives they were carrying to blow up the target. The result was dire: 14 Palmach fighters were killed.

About forty people, including a female soldier named Zahara Levitov, took part in the failed strike. It was just one of eleven similar actions carried out on what became known as the “Night of the Bridges”, an operation by the Haganah’s elite Palmach force which targeted strategic bridges and transportation routes used by the British Mandate authorities. Zahara sustained an eye injury in the explosion, but she managed to reach the nearby Kibbutz Matzuva. There, disguised as one of the children, she hid from the British forces in the children’s dormitory. The caregiver at the scene told the police they could not see her because she had a dangerous illness. The ruse worked, and although her injury was substantial, the British did not arrest her.

Zahara was not even 19 years old when she took part in the daring “Night of the Bridges” operation. She was born in Tel Aviv in 1927, the youngest of three siblings. She spent her early childhood in Kibbutz Kiryat Anavim, before returning with her family to Tel Aviv at the age of nine. While studying at the New High School in Tel Aviv, Zahara joined the Haganah and began her underground activities.

In the second year of Zahara’s service in the Palmach, she became a squad commander, teaching trainees at Ein Harod. There she also fell in love with Shmuel (Shmulik) Kaufman. Their romance became the basis of Devorah Omer’s best-selling book Until Death Do Us Part (Leʹehov Ad Mavet). The book is based, among other things, on the many letters they wrote to each other, which showed the young couple’s flair for writing. Shmulik, who was considered gifted, had planned to travel to the United States with Zahara in 1947. He was to study economics and she would study medicine.

Shmulik’s Palmach commanders tried to persuade him to stay in Israel due to the tense security situation, but in the end, after meeting with Yigal Alon, the head of the Palmach, Shmulik obtained his release permit. He asked Zahara to leave for Jerusalem right away, but she insisted they stay at the kibbutz for a few more days and organize a farewell party. Two days later, Shmulik was asked to help in grenade training at a neighboring kibbutz. A defective grenade exploded and Shmulik, not yet twenty, was killed, along with two other trainees.

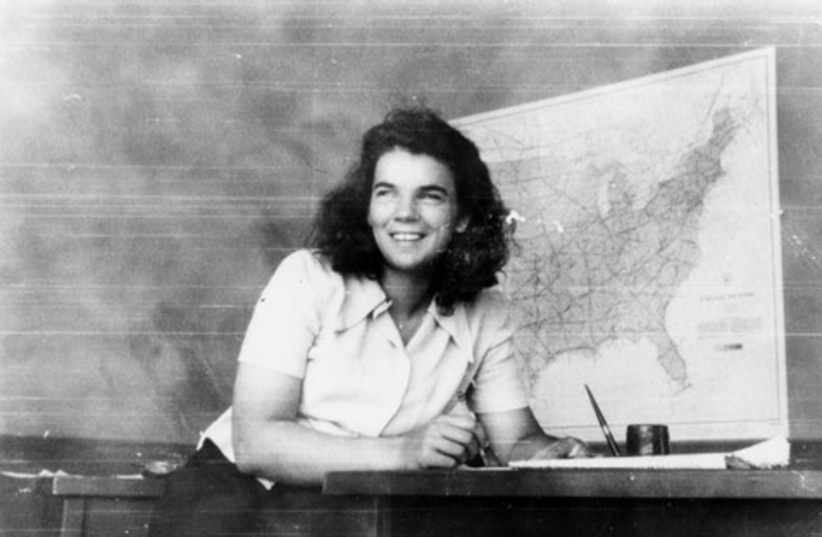

After several months, the broken-hearted Zahara traveled to the United States to begin medical school. She excelled in her studies and received a letter of recommendation that allowed her to transfer to Columbia University in New York. All the while, she continued writing letters to her beloved Shmulik, who was no longer among the living.

The news from Israel, and in particular the news about the fall of the Convoy of 35 during the War of Independence, many of whose members were friends and acquaintances, shocked Zahara. She left her studies and signed up for a pilot’s course that was being organized in California—she was one of only two women in the course. She completed it with distinction and returned to Israel as a licensed pilot. Her squadron was stationed at Tel Aviv’s Sde Dov airfield and she was soon appointed deputy commander. She embarked on long solo flights to keep in touch with isolated settlements whose only access was by air. She even set out on her first leave vacation by plane. Zahara flew to Jerusalem to meet with Shmulik’s father in order to prepare a memorial book about her beloved. She was scheduled to fly back to Tel Aviv on August 3rd, 1948, with pilot Emanuel Rothstein, but a malfunction caused the plane to crash in Jerusalem’s Valley of the Cross, killing both pilots. Zahara was just twenty years old.

At the time, the sisters Ruth and Reuma Schwartz (who would go on to marry Moshe Dayan and Ezer Weizman, respectively) were at their parents’ house in the Rehavia neighborhood, situated on the slopes of the valley. Ruth saw the plane crash from the kitchen window and she hurried with Reuma to the scene. In an interview with the newspaper Israel Hayom, she told about what she saw: “We arrived at the site and what I saw I will never forget. It was terrible. The two bodies were intact and lying next to the broken plane. Zahara was so beautiful. I do not remember him, but she—her black hair fell around her face. She had on a red shirt and a green skirt and she was lying there—whole, but still. What could we do? We opened the back doors of the car and loaded the bodies into the car with the feet sticking out and made our way up to the road. An ambulance took them from there.”

The tragic story of the young Zahara and Shmulik has been immortalized in a number of Hebrew books and plays. In the early years of the State of Israel, her story was a source of inspiration, and many girls were named after her. Zahara’s mother used to send a sweater to mothers who had named their daughter Zahara after her own. Over the years, the Israeli Air Force has also contributed to her commemoration as an iconic figure in Israeli history. Today, after many years of women not being able to serve as Air Force pilots in Israel, this possibility is now open to them once again.

This article originally appeared on The Librarians, the official online publication of the National Library of Israel dedicated to Jewish, Israeli, and Middle Eastern history, heritage and culture.