With the publication of the two-volume Palestine to Israel: Mandate to State, 1945-1948, Monty N. Penkower had completed his epic trilogy on the rise of the modern State of Israel, which he began with Palestine in Turmoil covering the period of 1933-1939. Penkower now has produced one more in which he presents to his readers additional relevant material he gathered that could not be included previously, thus enriching our knowledge and understanding of the history of this period of the Zionist movement and the rise of the State of Israel.

As is his style, Penkower’s presentation meticulously leads the reader through the maze of events, providing insight into how and why they happened; especially in this volume, we get to know the people who caused them to happen. The details are many, yet Penkower does not allow one to lose sight of the greater picture. The sources are at the end of each chapter, which saves the necessity of turning to the back of the book.

The reader is led through halls, hotel rooms, offices and the corridors of power. Documents, diaries, minutes, ephemera, and newspapers are laid out to provide a reliable account of the history.

Five chapters

There are five chapters in Israel: As a Phoenix Ascending. The first is devoted to the Zionist Congress of December 1946, the first after the world war and the loss of the critical mass of Jews in Europe expected to serve as the “troops” to create the national home. This was when the “moderates” were supporting Chaim Weizmann – who had forced upon the Hagana and the Palmah to disband the United Resistance Movement which for nine months had employed violence against the British rule in Mandate Palestine; and when the “extremists” were supporting Abba Hillel Silver over how to direct the anti-British policy of the World Zionist Organization. Moreover, on the agenda was the looming pro-state diplomatic maneuvering at the UN.

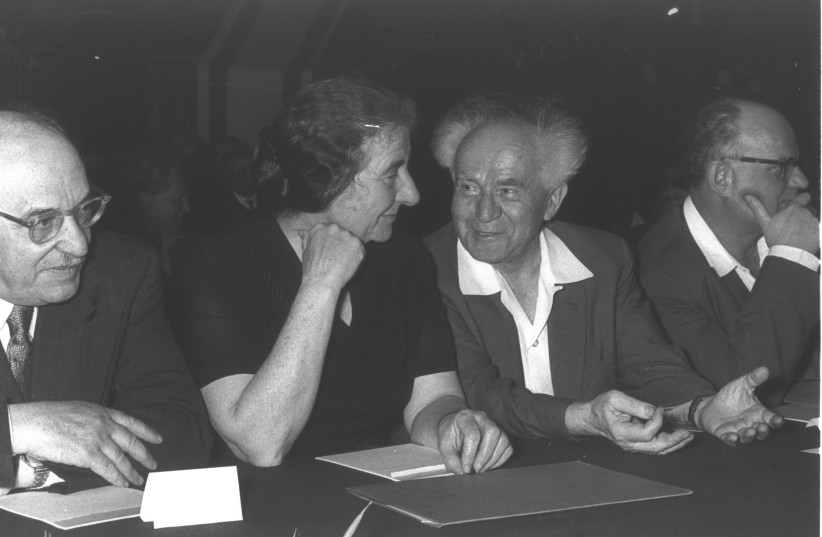

The second chapter is devoted to the financial campaign launched by the Yishuv and Golda Meir’s fundraising efforts, together with the remarkable organizational ability of certain American Jews, both Zionist and non-Zionist. It was clear to all that the Yishuv’s battle endeavors against the Arab aggression that had begun immediately following the UN Partition proposal of November 29, 1947, and the very existence of the Jews there, depended on what they could collect.

The three remaining chapters are devoted to Jacob Robinson, Clark M. Eichelberger and Judah Magnes. The first two worked to renew Jewish political and legal sovereignty; the third, chancellor and then president of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, died as the state fought for its survival throughout 1948. Magnes had sought, with help from antisemitic State Department officials, to convince US secretary of state George Marshall and president Harry Truman to adopt an approach that would have effectively, at that time, ended the hopes and aspirations of Jews to witness the renaissance of Zion.

PENKOWER explains that he chose the phoenix bird as a symbol, one found in Midrashic literature, because he identifies an ongoing resurrection-type character in the Jewish people which kept alive the effort to return to its national homeland through all the years of its dispersal. Penkower seeks to identify in his book how this Zionism belief, conviction and determination achieved Israel’s establishment.

This book adds much to our understanding of the hurdles that faced Jewish statehood. Penkower’s series of volumes flesh out history, deepen our perception and force us to appreciate what dedicated human beings can accomplish. And he has done so admirably.

There could have been some fine-tuning. For example, the first chapter on the 22nd Zionist Congress could have expanded more on the presence and activity of both Irgun and Stern Group agents who were present and who had distributed literature, working behind the scenes to strengthen the hands of those favoring active resistance.

Penkower notes there that Hashomer Hatza’ir, the political arm of the left-wing Marxist Kibbutz Artzi, was against partition; we learn that its leader, Meir Hazan, would not even sit with the Revisionist members of the new Executive. That could have presented an opportunity for a deeper understanding of the complexities of Zionist politics, the animus the Left displayed for the Right, as well as confronting today’s critics of Zionism from the Left for whom partition is the basis of their approach to the Arab conflict with Zionism.

Henry Montor is highlighted as being behind Meir’s success, but his 1940 role in refusing to intervene for a Revisionist-sponsored refugee ship stranded on the Danube is missing. He had written an infamous letter to American rabbis that said, “Palestine cannot be flooded with… old people or with undesirables,” adding, “many of those who have been brought into Palestine by the Revisionists… have been prostitutes and criminals.” But these are minor observations.

Penkower’s last chapter, in which he reviews the last diplomatic battle against the US trusteeship proposal, includes the intervention, sponsored by the State Department, of the Hebrew University’s Magnes. Driven by his vision of bi-nationalism, Magnes met with secretary of state George Marshall on May 4 and, the next day, with president Truman. Magnes, astoundingly, requested that the US “impose even partial financial sanctions” on Israel.

He informed them that “the Jewish community in Palestine is an artificial development” and added, according to the official minutes, that “if contributions from the United States were cut off, the Jewish war machine in Palestine would come to a halt for lack of financial fuel.”

Penkower has accomplished an important task of transmitting history and adds much to our understanding of those two crucial, complex years.