Award-winning filmmaker Richard Trank, the director of Never Stop Dreaming: The Life and Legacy of Shimon Peres, now running on Netflix, describes his career as “accidental.” Initially, his goal was to be a novelist. But to make a living, he worked as a writer-producer in news and public affairs programming for radio. That got the attention of the Simon Wiesenthal Center. Coming on board, he produced a show for the center that ran on around 125 commercial radio stations across the United States. That led to a number of projects documenting the oral histories of Holocaust survivors, educational and promotional films, and museum films.

For more stories from The Media Line go to themedialine.org

In 1991, Trank co-produced Echoes That Remain, a film on Eastern European Jewry before the Holocaust. Since then, he has worked as a writer, director, and producer on around 15 projects for the Wiesenthal Center’s Moriah Films, including The Long Way Home, a documentary on the post-World War II Jewish refugee situation from liberation to the establishment of the State of Israel, which won an Academy Award as best documentary feature film in 1997.

He also works as the director of content for the Wiesenthal Center’s Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles and for the new Museum of Tolerance in Jerusalem, which is scheduled to open to the public in 2023.

Trank joined The Media Line’s Felice Friedson for an in-depth discussion about Never Stop Dreaming, his 2018 film on Israel’s storied statesman, president, and twice prime minister, Shimon Peres.

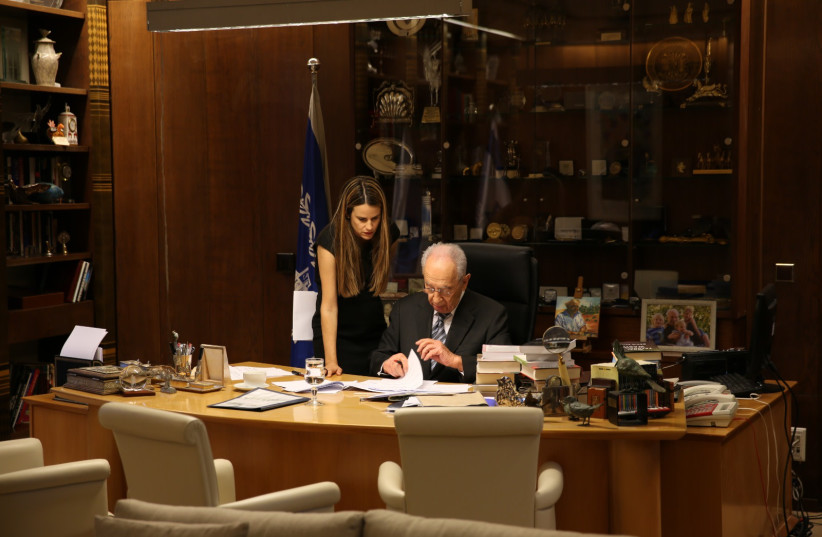

For Israel watchers or anyone with an affinity for the Middle East, it won’t seem unusual to see a film about an old man with a thick accent being fêted by celebrities and world figures half his age. But Shimon Peres was larger than life and to many the face of the Jewish state. By way of the example before us, there aren’t a whole lot of biopics about Israeli leaders taking up space on the Netflix playlist. But Never Stop Dreaming: The Life and Legacy of Shimon Peres is on the list and is being viewed by people around the world.

Interview

TML: Thank you for joining me at The Media Line.

Trank: It’s a pleasure to be here.

TML: Richard, your filmography is an impressive tribute to leadership and peace. You did the Peres film several years ago, so how did Netflix become interested in this project, and who decided on the release date?

Trank: We began working on this film in 2016. We had been working on a film, starting a film on David Ben-Gurion, and in December of 2015, we interviewed Shimon Peres for that film, because he was the last living link to Ben-Gurion. And as we were tweaking lights and doing final things on the cameras, one of the aides came up to me and said, “You know, you’ve made all these films about different people. Why don’t you want to make a film about Shimon?” – everybody there called him by his first name. And I said I would love nothing more than to do that. In fact, I asked him when he was president in 2012, because we interviewed him for another project, about Theodor Herzl, I said to him, “Mr. President, you don’t have to tell me an answer today, or tomorrow, or even a week from tomorrow, but I’d love to make a film about your life.” And he started chuckling and he said, “Ugh, who would want to see such a film.” And I told that to his aide, and she said, “Well, you asked the wrong person.

You should have asked one of us. Because he’s very modest, he’s not interested in doing things like that.” Are you serious? My boss was with me, Rabbi Marvin Hier. And he said nothing would be more of an honor for us than to do that. So, we stayed around for a couple of days and worked out an understanding, and, starting that January, we began doing interviews with Shimon Peres. I did about 50, 60 hours of interviews with him from January of 2016 until late-ish July of 2016. We finished all of our principal interviews, and then that fall I was supposed to be going on a lecture tour with him to Canada, excuse me, to China. We were with him in Canada for one of his last public appearances, and then we were going to follow him to China. And then he suffered the stroke that took his life.

TML: Richard, your film on one level is an obituary, delivered by the man himself. It presents material from many hours of on-camera interviews with Shimon Peres filmed shortly before his death. Which came first, the desire to tell the story, or the opportunity you had in the form of access?

Trank: It was the access, and the idea when we started to film – he was a very vibrant 92-year-old man, he was almost 93. And the idea was we would make this film about this vibrant man in his 90s who is still inspiring people all over Israel and around the world, advising world leaders. And the idea was we’d have it finished and Shimon Peres would be sitting in the audience for the premiere in Israel.

But then he suffered the stroke that took his life, and it became a legacy film as opposed to the kind of film I started out doing. I always say that documentary filmmaking is kind of like improvisational theater – you never quite know what somebody is going to throw at you, and you have to go with what’s been thrown at you. So, in this case, it took some rethinking, and we spent the next … we finished the film actually just before … in 2019, so a few months before the pandemic. And then everything kind of stopped, because the idea was to put it out for theatrical release. And I always had this desire that it should be on Netflix. I told that to President Peres. I had told him that my idea for a narrator was George Clooney, and he loved that idea. So, it was just as the pandemic was happening that Netflix saw a version of the film and they loved it and they decided that they’d take it on as an “[Netflix] original” rather than just licensing it. Part of what I was doing in the early part of the pandemic was things that we needed to do in order to meet all the requirements that Netflix had for the movie.

TML: Had you ever met Shimon Peres at a younger point of his life, or was it only towards the end?

Trank: I met Shimon Peres for the first time in the late ’80s. I was a radio reporter. I was actually doing a radio series at the time for the Wiesenthal Center. That’s when I went to work there. So, I interviewed him – he was on a trip to LA and I interviewed him for that. And then I was working on another project in the ’90s, when he had lost to [Binyamin] Bibi Netanyahu [in the 1996 election] and was out of office, and interviewed him at Labor party headquarters in Tel Aviv. It was at a time in his life that wasn’t a particularly happy time for him politically or personally. But he gave this amazing interview for a film of mine called In Search of Peace. And then, over the years, I would interview him for various things and see him at events that we did. It’s not like I could say, oh, he was a good friend, but I knew Shimon Peres from a professional perspective for, I guess, more than 30 years.

TML: What is your search for peace?

Trank: My search for peace? My search for peace is searching to see how peace can be made. Because a lot of my films have dealt with Israel’s ongoing attempt to find a way to live peacefully with its neighbors. This is why Shimon Peres was such an inspiration to me. Because he was always somebody who always took the long view of history, the long view of things. And considering how complicated the political landscape is, not just in the Middle East as a macro, but in Israel as a micro, sometimes deciding simple things is very difficult. So, making peace, which is a much bigger issue, is something that isn’t going to happen overnight. That was one thing he and I talked about was that just because you don’t achieve something the first time, that doesn’t mean you can’t keep trying. And you can’t keep dreaming that you’ll get there one day.

TML: There are two tracks to your film: the personality, and the public servant, separate and together. Was it difficult to write?

Trank: It was an interesting thing to write. And, luckily, because he’d written a number of books and there was Michael Bar-Zohar’s biography and a couple of other biographies. So, there was a lot there. And then these interviews were incredible. He really opened up about all sorts of different stories. I think he had a sense that he didn’t have much time left. His son, Chemi, had told me – because at the same time we were doing these interviews he was writing what became his last book. And Chemi said to me that he thought his father had this premonition that he wasn’t going to be around much longer and there was this sense of urgency to really tell the story, which is why he opened up the way that he did. Because other people had tried to do films with him, but I don’t think anyone has done a film like the one we did. Part of it was because I got this access and got other people to speak to us as well about him.

TML: Peres had the knack of being in the right place, that is holding the right portfolio at the right time so that he himself became part of the story. As a writer and director, did you have to choose between history and the man?

Trank: Well, you don’t want this to just be a dry recitation of historical facts. So, I tried to balance telling some history, because there are people who are watching the film who know very little about Israeli history. But, also, I wanted people to get to know this man who, at a time when Israel was this country struggling to just provide the essentials to its population, he was dreaming these dreams of Israel as a high-tech center, Israel as a scientific and a medical center. People thought he was talking like a crazy person because the country was struggling economically. So, I wanted people to also get to know this dreamer, in addition to learning a little bit about Israeli history.

TML: The two-hour running time is indicative of Peres’ long and productive life. But while there are allusions to political battles, and even the humiliation of his loss to Moshe Katsav in his first presidential bid, we didn’t hear his political foes explain what made him so formidable an opponent. What about Shimon Peres do you think got under their skin?

Trank: I think part of it was his refusal to give up. He kept going. Bill Clinton says in this movie that no matter what it was that knocked him down, he always got up. My favorite sports are tennis and baseball. So, maybe look at it like Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer are playing in the finals at Wimbledon, and they’re tied 6-6, and then 7-6, and then 7-7, and it keeps going on and on and on, and neither one of them ever gives up until somebody makes the wrong move. And it was kind of that refusal to give up. But, also his ability to adapt and consider changing sometimes. And that in some respects caused him to be criticized by political allies who felt that he was too willing to bend. If you look at what happened in the early 2000s when he joined [the] Kadima [party] with Ariel Sharon. There were a lot of people in the Labor party who didn’t ever forgive him for doing that, but he saw the opportunity that Kadima presented and he went with it. And I think that was a lot of his life. Seeing an opportunity, taking advantage of it, and moving ahead. And it wasn’t about him, it was about whatever the issue was. So, one time he said to me, “Look, like anyone else I have an ego.” But at the same time, as much as he might have had an ego, his ego never got in the way of what was best for the State of Israel.

TML: What was it like for you, as the filmmaker with the concept, sitting with former presidents, on this particular issue?

Trank: It was interesting. I was lucky in that I had interviewed Bill Clinton twice before. So, I kind of knew what to expect with Bill Clinton. Like what they tell you: Don’t expect him to be on time. If they tell you you’ve got 15 minutes with him, you’re going to have 45 minutes with him. Which is always great, because you always want more than less, although when you’ve got a staff that wants him to only stick with 15 minutes and you’re dealing with that. So, I knew with Bill Clinton, I knew he’d be great, I knew how he’d jumped at the opportunity to do this. With Barack Obama, I was hoping he’d say yes. He had just come out of office and we were fortunate enough to get the second interview that he gave after leaving office. What I was told about Barack Obama was, he’ll be on time. If they tell you he’s got 20 minutes, you are going to get 20 minutes, but it’s going to be a really good 20 minutes. And that’s what we got. He was excellent, he gave a perspective that I thought was an important perspective. It was very interesting interviewing George W. Bush, because I didn’t know quite what to expect, and it was such a wonderful experience. He had these nice memories of him [Peres] because he knew him from the time that his father was vice president and president. So, there was another perspective there. Tony Blair, the same thing. He was very open to doing it. He so looked up to Shimon Peres as a model. I call this like an embarrassment of riches that I got with this movie, because as soon as they knew who it was going to be about, very few people, I mean, nobody said no. I mean Barbra Streisand, who is not an easy get, she said yes. It was wonderful.

TML: You paint a picture of achievements whose impact remains for a long period. Building of a new nation’s defense industries, enabling Israel’s nuclear program, the ill-fated Jerusalem Agreement, and the Oslo Accords. How do you think Peres always landed in the epicenter of events?

Trank: Well, because from the beginning he was in the middle of it all, as a young man. He helped to build Israel’s navy in the War of Independence years. He was there working with people like Teddy Kollek bringing in weapons, illegally, to help Israel during the War of Independence. And he saw a door opening a little – he opened it a big way. Because when he began a relationship, a military relationship, with the French, Golda Meir was the foreign minister. And she was focusing on America, not on Europe. And people don’t realize that at the time Israel had no way of getting the weapons it needed to defend itself. When he saw this opening with the French, he jumped on it. It upset Golda tremendously. She would complain to [Prime Minister] Levi Eshkol that “he doesn’t respect me, he’s going around me.” But he saw these openings, and it wasn’t because he was trying to get attention for himself, he saw something that was going to help the State of Israel. So, he just happened to always be in the right place at the right time. But, ironically, even being in the right place at the right time didn’t assure him of political success all the time. He was oftentimes on the outside, always coming up short when it came to the prime minister’s office. Even at a point in his life when he shouldn’t have had to worry about winning the presidency in the Knesset [vote], he was humiliated when they brought Katsav in at the last moment and he became president. So, even though he was never out of the public eye, sometimes he was in the public eye but not for reasons that somebody would want to be.

TML: Each story you told involved a supporting cast. How do you decide what gets chopped? There are people that are left out, too, and definitely part of the story.

Trank: Right. You know, it’s a difficult situation. I was lucky that I could take two hours. I could have made a miniseries about this. But you look at certain moments and you have to go with those moments. We did deal, I think, with every single prime minister. We dealt with a lot of major things. But we also, I look for things that people didn’t know about as well. And I also wanted to give people a sense of his background, where he came from, who his grandfather was. People sometimes forget that this was a man who came to this country before it was Israel, when he was, 10, 11 years old, from a place that nobody has ever really ever heard of, Vishnyeva, in what is now Belarus. He wasn’t a sabra; in some ways that was held against him. So, there were parts of the story that I felt it was important for people to know because this was the only time I was going to tell this story.

TML: As exciting as his public life was, the status he achieved in his later years as an international icon was fascinating. What made Shimon Peres so attractive to the young, the powerful and famous?

Trank: You know, I think that sometimes as people get older, certain things that might have been held against them when they were younger, people let it go. And the fact is, I don’t think people today give enough respect to experience. In the movie business, television business, if you’re over 45, you’re considered a has-been. In politics it’s a little bit different – look, we have a 79-year-old [US] president right now who defeated a 75-year-old president. So sometimes in politics, there’s a little bit more forgiveness. But I think, because of what he represented, the kind of leadership that he represented, he became an inspiration in his 80s and his 90s in a way that he didn’t when he was in his 40s and his 50s. In fact, it’s interesting, I think he really hit his stride around the time he hit 70. Because if you look back, let’s say, at Oslo, he was about 70 years old when he was in the center of the Oslo Agreement. There are not a lot of people at 70 that are achieving things like that. And then you take a look at him as president, and he was well into his 80s, and he redefined what that position was in the State of Israel. He made it an important office in a way that it never had been because it had been a ceremonial office. So, he laid the groundwork for President [Reuven] Rivlin, and now President [Isaac] Herzog.

TML: As I mentioned earlier, you very much like filmmaking around presidents, leaders, and peace. So, what’s undone? What’s the next big project you still want to do?

Trank: Well, there’s a few. The one that I’m now finishing was the one we started when we first embarked on this journey, and that was the film about David Ben-Gurion. So hopefully by year’s end, we’ll be finished with that movie, and we’ll see where we go with that one. There’s a limited series that I’ve been kicking around on the issue of antisemitism around the world. That’s something that I’m hoping to interest either Netflix or Amazon – one of the big… hopefully, we’ll have an ongoing relationship with Netflix. But there’s that movie. There are some other stories that I’d love to tell, stories about Israel. I always thought I’ll never do another film about the Shoah because I’ve done five or six films about the Holocaust. And every time I think there’s no more stories to tell, you find a story that you didn’t know about that might open up the subject to people who don’t know much about it.

TML: Richard Trank, I really appreciate you joining us here at The Media Line and sharing a little bit of behind the scenes of this new movie that is out by Netflix. Well not so new but it’s new to the audience, and I wish you lots of success.

Trank: Thank you.