In 1972, Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci interviewed Golda Meir, Israel’s only female prime minister.

“Shall we talk about the woman [David] Ben-Gurion called ‘the ablest man in my cabinet?’” Fallaci asked. “What does it really mean?” Meir replied: “That it is better to be a man than a woman, a principle on which I don’t agree at all... And what if Ben-Gurion had said, ‘The men in my cabinet are as able as women’? Men always feel so superior.”

“What does it really mean? That it is better to be a man than a woman, a principle on which I don’t agree at all... And what if Ben-Gurion had said, ‘The men in my cabinet are as able as women’? Men always feel so superior.”

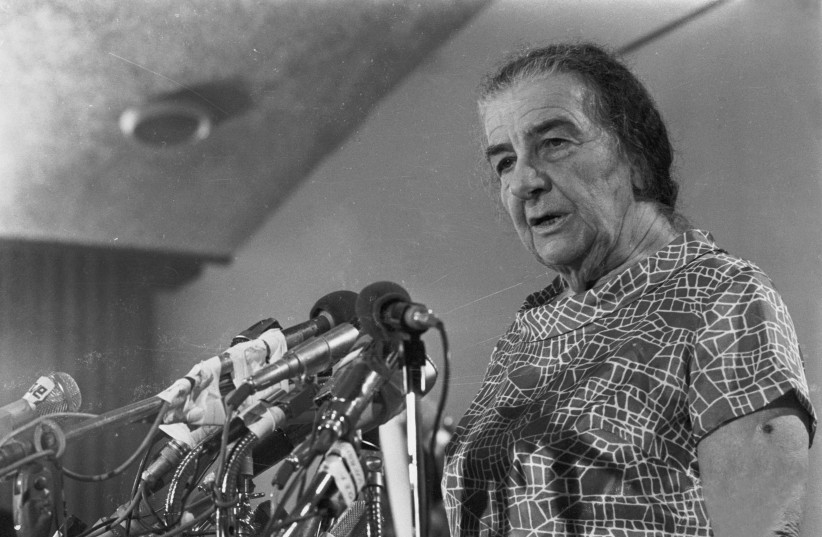

Israeli prime minister Golda Meir

When Fallaci declared that “The Women’s Liberation Movement will like that, Mrs. Meir,” Golda was not pleased. “Do you mean those crazy women who burn their bras and go around disheveled and hate men... how can one accept such crazy women who think it’s a misfortune to get pregnant and a disaster to bring children into the world?... I have lived and worked with men all my life, and yet to me the fact of being a woman has never, never I say, been an obstacle. It’s never made me uncomfortable or given me an inferiority complex. Men have always been good to me.”

This response, Pnina Lahav indicates, may reflect Meir’s view that professionally ambitious Israeli women should deny the existence of gender-based discrimination and avoid alienating men. It certainly belies the facts of her life.

An emerita professor of law and member of the Elie Wiesel Center of Judaic Studies at Boston University, Lahav is the author of Judgment in Jerusalem: Judge Simon Agranat and the Zionist Century.

In The Only Woman in the Room, she examines the life of Golda Meir through a feminist lens. Lahav follows Meir from her birth as Golda Mabovitz in Pinsk, Belarus, to her formative years in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; marriage to and separation from Morris Myerson; a decision in 1922 to leave the United States to go to Palestine and join a kibbutz; relinquishing the care of her children in order to work in the Labor movement; and her climb up the political ladder in Israel.

“The breadcrumbs of gender discrimination,” Lahav claims, “were visible throughout her long journey to the top, from her parents’ initial refusal to let her become a teacher to the misogynistic attacks she suffered as prime minister.”

Lahav provides abundant evidence of that discrimination. A year after Meir was appointed foreign minister, for example, Walter Eytan, the ministry’s director-general, declared “Women play an important part in the Foreign Service – as their husbands’ wives.” An article in a political magazine predicted that as prime minister she would bring hatred, “a typical feminine quality,” to governance.

That said, Lahav faces substantial challenges in The Only Woman in the Room. Meir was not inclined to self-reflection. A political pragmatist, she may or may not have publicly endorsed stereotypes about marriage, motherhood, housewifery and professional ambition for tactical or strategic reasons. And, apparently, very few contemporaneous sources shed light on the motivations for her behavior. Consequently, The Only Woman in the Room often relies on Lahav’s speculations about Meir’s attitudes toward gender-based identity, women’s roles and women’s rights.

Lahav indicates that opposition to women’s suffrage in the United States is “hard to reconcile” with Meir’s experiences but acknowledges she “might have been conflicted.” She thinks it “not farfetched” that Meir saw similarities between the American frontier, “a territory waiting to be tamed and cultivated by white settlers,” and Labor Zionism.

Lahav imagines Meir contemplating marriage to David Remez and concluding “Who needs it?” Lahav wonders if the notoriously promiscuous Meir had a Palestinian lover. She suggests that Golda’s American education, with its focus on the Civil War and the daily recitation of a pledge of allegiance to “one nation, indivisible,” played “an unconscious role” in her rejection of two states – one Jewish and the other Palestinian.

According to Lahav, during the Suez Crisis of 1956, Meir demonstrated “maternal concern” for Ben-Gurion, who was “fretting like a boy.” Marginalized during negotiations between US secretary of state John Foster Dulles and Abba Eban, she “appeared to suffer pain akin to that felt by victims of sexual assault, even rape” and emerged from the diplomatic battle “a battered woman.”

As prime minister, Lahav maintains, Meir deployed a piercing gaze to transform her “from an object looked at by the men around the cabinet table into a subject projecting agency and control.” She did not familiarize herself with military affairs prior to the Yom Kippur War because she internalized the belief that it was “the business of men.” She took the reins after the initial attack “only because no one else stepped up to the plate.”

It’s hard to know what to make of these speculative judgments. Or why Lahav tells us that to prepare for the ceremony proclaiming a Jewish state, Meir “washed her long, thick hair,” selected a “little black dress in the French style,” may have put on makeup and “probably powdered her nose in anticipation of the presence of cameras.”

Nonetheless, Lahav is on much firmer ground in concluding that many of the unflattering opinions among Israelis about Meir’s tenure as prime minister were rooted in misogyny. That Israelis have come to express “a different, equally meaningful and equally deep sentiment” about her, affirming that she stood for “the power to face adversity, remain resilient, to be oneself.” And that they made the right judgment in ignoring the provision in her will forbidding “naming anything after me.”

The writer is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Professor of American Studies at Cornell University.

The Only Woman In The Room: Golda Meir And Her Path To Power.

By Pnina Lahav

Princeton University Press

376 pages; $35