Israel’s long-serving prime minister (1996-1999; 2009-2021) tells the story of his family, his path to leadership, and his commitment to defending the Jewish state and securing its future.

<br>Back in Israel: Blissful Years 1959–1963

In 1959, Father ended his leave from the encyclopedia. We made the sea voyage back to Israel on the ocean liner Israel, stopping in Gibraltar to feed the monkeys and in Athens to tour the Acropolis. The Katamon neighborhood kids greeted us like returning heroes. Unfortunately for me, the language problem resurfaced, this time in reverse. In America I had to learn English; in Israel I had to recover my Hebrew, which had fallen behind. When my report card showed average grades, my mother looked at it and said, “You know, Bibi, you can do better.” It was the only time in my life that I can recall even the mildest pressure for performance from my mother.

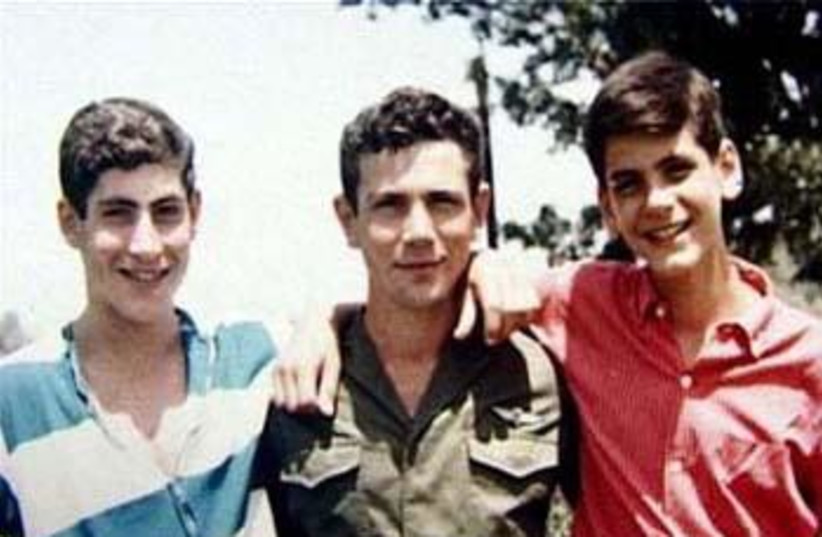

Biographies of me often include descriptions of my parents supposedly pushing Yoni, Iddo, and me to excel. This was simply not true. Our parents didn’t need to push us. We were competitive by nature.

Yoni set the standard. By his early teens he was brown-haired and handsome, of medium height and athletic build, with high cheekbones, a captivating grin, and penetrating brown eyes. He was a star pupil, much admired by teachers and peers alike. Taking my cue from him, I quickly improved my grades. Visiting my elementary school some fifty years later, I was presented with the evaluation of Mrs. Ruth Rubenstein, my sixth-grade teacher. She characterized me (as she must have characterized many others) as someone who “grasps things fast, is active, civil and responsible, reads, carries out his duties with precision and timeliness, is socially integrated, happy, brave.”

Where she got “brave” from I have no idea, because I don’t remember anything in those years that required courage. But I was sufficiently “socially integrated” to attempt my first, and for the next twenty-six years my only, venture into politics. I was elected class president at the grand age of twelve. It was, I remember, astonishingly easy to get elected. All you had to do was be nice to everyone.

Though I was socially accepted, certain qualities separated me from my peers. I was bigger and matured earlier than most of my classmates (a gap that eventually corrected itself ), and almost none of them had lived or even traveled abroad.

I briefly joined but never immersed myself in the Israeli branch of the international scouts movement, unlike Yoni, who had become a devoted scout leader, idolized by the youngsters in his charge. When I was twelve, Yoni, relying on my drawing skills, asked me to design a pennant for his troop. He was delighted by what I produced, and when the kids in Yoni’s scout troop saw the pennant, they asked me why I didn’t rejoin.

I answered in jest that I was afraid I’d fail the test of knotting ropes. They didn’t get the joke. “No, Bibi, you don’t have to worry. You’re sure to pass it.”

Some of my friends had parents with concentration camp numbers tattooed on their forearms. This was seldom spoken of in the open, until the capture of the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann. Seized by Mossad agents in Argentina in 1960, Eichmann was brought to Israel to stand trial.

“What do you think is the best punishment for him?” Mrs. Rubenstein asked our class.

She heard us out and then answered her own question: “The best revenge is to take him around the country and show him what we’ve done here.”

The court thought otherwise. Eichmann was sentenced to death, the only person in Israel’s history to be executed. Years later I would offer a different answer to Mrs. Rubenstein’s question. The most important response to Eichmann and his boss Hitler was to ensure that such a horror never befalls the Jewish people again. My standing with my classmates took a hit when some of them received acceptance letters to an elite junior high school to which we had all applied. I had not received such a letter. Noticing my somber mood, my mother asked me what the problem was.

“Nothing,” I said.

She persisted. Finally, I revealed the source of my misery.

“Oh my God,” she said.

“You mean this envelope? It’s been lying here for weeks.”

Thus I entered the prestigious Leyada School.

IN THOSE days most Israeli children studied the same core curriculum, consisting of Bible study (more historic and literary than religious), Hebrew, math, history, geography, science, some sampling of the Jewish Oral Law, and English (a freebie for me).

Although most of my friends came from homes that supported the Labor Party in politics, there was no palpable divide among us children.

Besides, though my father had decidedly conservative leanings, he didn’t belong to any party and we never discussed party politics at home. He certainly didn’t disparage Israel’s government in front of his children.

I distinctly remember one telling exception that occurred soon after we moved to our new home on Haportzim Street in 1953. Our house adjoined a beautiful Arab-style residence that the government had requisitioned to serve as the home of Finance Minister Levi Eshkol, who later replaced David Ben-Gurion as prime minister. One day a caravan of government cars stormed into the neighborhood and stopped in front of the residence. All the neighborhood children were shocked to see the spectacle of VIPs coming out of those limousines. My father and I went out to the porch to take in the scene.

After a moment Father dismissively uttered one word, “Pkidim” (bureaucrats), and went back inside the house. This was undoubtedly the germination of a lifelong skepticism toward bureaucracy that I’ve carried with me ever since.

Yet I remember this incident precisely because it was so rare. If my parents’ ideological beliefs were evident at all, it was only during family occasions like my Bar Mitzvah party, which was held in our Haportzim Street home. Among the guests were many prominent right-of-center writers and intellectuals, some of whom, like the great poet Uri Zvi Greenberg, have since assumed legendary fame and whose inscriptions I cherish in the books they gifted me.

MY BAR mitzvah was marred by my father’s acute appendicitis. His fiercely loyal brothers filled his place and accompanied me to the President’s Synagogue in the Rehavia neighborhood to read the customary portion of the Bible, where I had to deal with another challenge. The reading that week was from [The Book of] Kings 1, describing how the aging King David took Avishag, the Shunammite woman, to warm his bed. Somehow I made it through the embarrassing text. In this and in so many other events of my early years, Yoni always stood by my side.

He continued to be admired by all. In an athletic competition between high schools in Jerusalem, he won the broad jump for his school and twisted his ankle on the landing. His schoolmates, elated by the victory he gave them, carried him on their shoulders all the way home. I was reminded of this incident years later, when Yoni was still alive, when I read A. E. Housman’s poem “To an Athlete Dying Young”:

The time you won your town the race

We chaired you through the market-place;

Man and boy stood cheering by,

And home we brought you shoulder-high.

After Entebbe, when Yoni was carried home by his grieving soldiers, this poem echoed in my mind with its full tragic force. While Yoni and I were as close as two brothers could be, he cared with equal devotion for Iddo. One day, as seven-year-old Iddo walked home from school, he saw a bent old lady dressed in black walking toward him with what looked to him like a stove on her back and a cane in her hand. Reminded of a Grimm fairy tale, he decided she was a witch out to hunt little boys.

Seeing Yoni with a group of his friends not far away, Iddo ran to them.

“What’s the matter, Iddo?” Yoni asked him. “What happened to you?”

“A witch,” Iddo panted, pointing breathlessly to the nearby field. “I see a witch!”

Howls of laughter erupted from Yoni’s friends.

“A witch, he sees a witch,” they taunted. Iddo grew ever more dejected for not being believed.

Yoni remained quiet. Seeing this, his friends stopped laughing. Yoni put his arm around Iddo’s shoulders and walked his little brother home. A short time later a friend gave Iddo a little sparrow he found in the woods. Iddo was delighted with his newfound pet. He put it in a cardboard box with a screen, padded the cage with dry grass, scattered bread crumbs in it and put in a tiny dish of water.

“You know what dror [sparrow in Hebrew, also the word for “liberty”] means?” Yoni gently asked Iddo. “It means freedom. That’s why this bird is called ‘freedom.’ Because it can’t live without it.”

Iddo set the bird free.

The next year, the three of us were sitting in the long entrance hall of our home. “You’re in the desert with another person, and you only have one canteen of water,” I said, presenting Yoni with the classic Talmudic dilemma.

“Either of you would need to drink all the water in the canteen to save himself. You can’t split it. What would you do, take it for yourself or give it to the other person?”

Yoni thought a moment before answering. Then he said, “It would depend on who the other person was. If it were Iddo, let’s say, I’d give him the water.”

Iddo and I looked at our 15-year-old brother and we knew: he would do it.

ONE AFTERNOON in 1962, my parents announced that our blissful years in Israel were coming to an end. They brought all three of us into our dining room to break the news that we would go to America once again for a few years so Father could again pursue his historical research while teaching graduate and doctoral students at Dropsie College in Philadelphia (it later became part of the University of Pennsylvania).

We broke into tears. Our world collapsed. Yoni was an ardent scout leader and class president. Iddo and I would have to leave our classmates again. Our second journey to America had none of the excitement of our first visit. We knew America, we liked many things in America, but America was not our home. Yoni considered staying in Israel for his remaining year and a half in high school but decided against it. He gritted his teeth and came along.

Yoni knew that at eighteen he would leave home and go to the army. “This,” he explained, “is the last time I would live with Father and Mother.”

‘Bibi: My Story’ will be released by Simon & Schuster on October 18.