Israel. A pulsating society, comprising Jews from distinct ethnicities and varied traditions, living alongside their equally diverse Arab, Druze, Bedouin, Muslim and Christian neighbors.

Vital, vibrant and vivacious.

But also precarious.

All of us living here, and anyone following our five elections in the space of three and a half years, would have a hard time not recognizing this fragility. The multiplicity of identities and beliefs extant in the country today, while potentially enriching, also pose a clear and present danger to Israel’s future. That was frighteningly apparent when, just before the collapse of the last government, then-prime minister Naftali Bennett received death threats in the mail, accompanied by bullets. The seriousness with which that danger needed to be assessed was underscored by the commemoration earlier this month of Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination 27 years ago.

Is it comforting or alarming, then, to recognize that Israel has always been at war with itself?

The yahrzeit this week of Israel’s fifth president, Yitzhak Navon, is a fitting occasion for such reflection.

His legacy, more than anything else, is the imperative of striving for social cohesion, of ensuring that Israel becomes the shared society its visionaries and founding generation believed in, a country in which all its citizens feel they belong and for whose future they all feel responsible.

“Israel is a complex mosaic of communities, cultures, traditions and values, where each yearns for recognition of its unique identity and contribution to society,” he observed after he became president in 1978. Well aware, however, of the inherent difficulties in fulfilling these aspirations yet determined to facilitate their realization, he continued:

“The goals I set for myself were to increase national cohesion, strengthen identification with the state, and fortify the sense of partnership between all segments of the population."

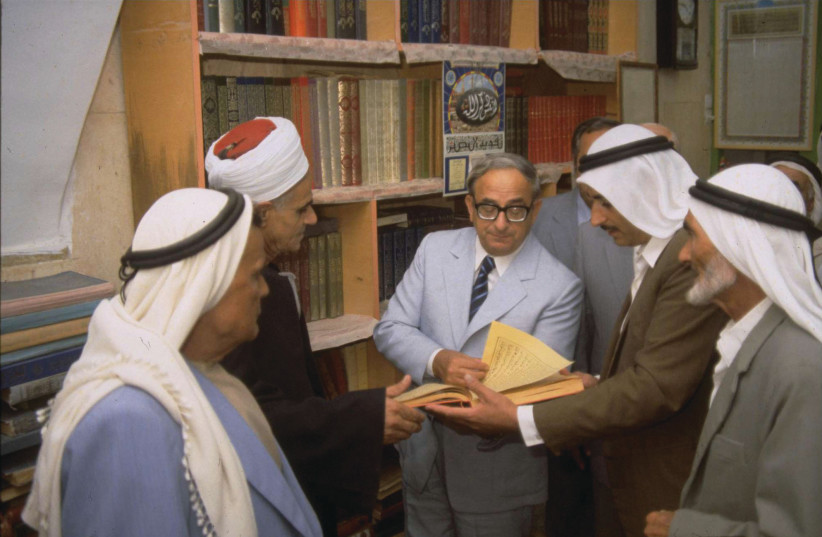

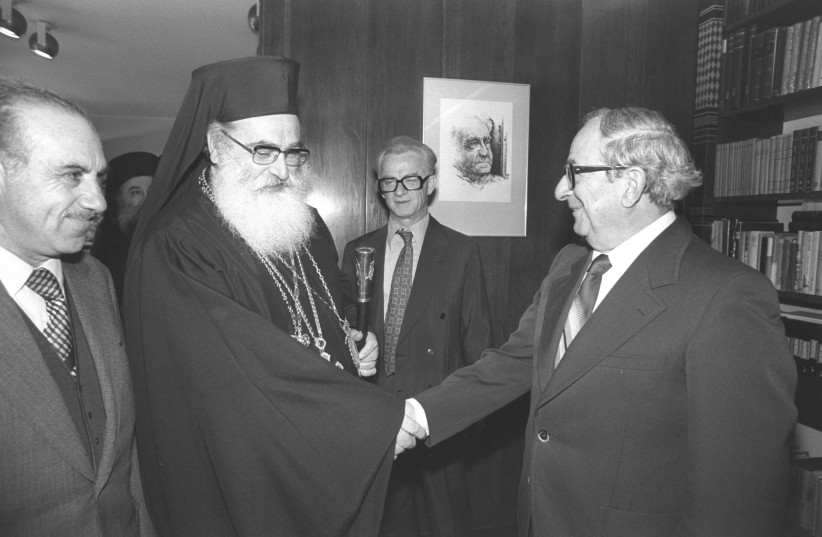

Fifth Israeli president Yitzhak Navon

“That there are differences between us is nothing new,” he observed, noting that “the question is whether we are able to bear different positions just as we bear different faces.

“The issue is not whether there will be disagreements among us but how we will manage them,“ he concluded.

He also went on to add a word of warning, as if he were addressing the incoming Knesset, “It is our capacity for dialogue across different segments of society that fuels our strength and resilience,” he cautioned.

Israel on the verge of social disintegration

THAT CAPACITY appears to be severely depleted and in urgent need of invigoration. Having yet to internalize Navon’s counsel, Israel now faces the very real danger of social disintegration.

In the midst of our unprecedented cycle of elections, the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) highlighted in its report on Challenges to Societal Resilience, “an accelerated trend of weakening social solidarity within social groups, between social groups and the state, and between the individual and the state… characterized by deepening public disputes stemming from diverse worldviews, especially regarding the necessary balance between national and religious values and democratic, liberal, secular ideals… aggravated even further by divisive, extreme, and superficial political discourse.”

It concluded with a warning of “risks and crises in four main domains: undermining of the delicate balance regarding Israel’s identity as a Jewish and democratic state, especially in its tilting toward the Jewish pole at the expense of the democratic pillar; the deepening of social and economic gaps; the transformation of the public discourse in Israel into a violent struggle of hatred and exclusion of the ‘other’; and the consequent weakening of societal resilience in Israel.”

These conclusions were echoed by the Jewish People Policy Institute in its annual Pluralism Index released six months ago. This year, the study focused on attitudes of and toward the Arab and haredi sectors, which respectively comprise more than 20% and 12% of Israel’s population. Together constituting a full third of all Israelis, the report notes, they cannot be dismissed as small minority groups, such that the survey’s revelations present worrisome challenges to the social cohesion of Israeli society.

While 88% of left-leaning respondents believe that all Israelis – Jews and non-Jews – share a common future, only 28% of its right-leaning citizens are so inclined. In the political realm, the study reveals that “secular Jews aspire to political partnership with Arabs but not with haredim; religious and haredi Jews aspire to political partnership with secular Jews but not with Arabs.” On the social level, the reality is that different ethnic and religious groups generally live in distinct residential areas and attend separate schools, such that interaction between them is low.

While the report notes that according to some this separation reduces tension and friction, it also raises the concern of others that our lack of familiarity with one another is responsible for growing suspicion of and animosity toward those dissimilar from oneself, whether Arab or Jewish, a position Navon would undoubtedly have endorsed: “I believe it is absolutely vital that we get to know one another better because people tend to hate what they do not know. If we don’t make an effort to get to know one another, we reject the only ground upon which trust can be built.”

As disturbing as the implications of these observations are for Israeli society, the INSS cautioned that these trends could “also impact negatively on the increasingly sensitive relationship between Israel and Diaspora Jewry.”

Israel's relationship with the Jewish diaspora

THAT RELATIONSHIP is indeed at risk. Over the past several years, a series of studies have revealed an ever-increasing degree of distancing from Israel on the part of Jews around the world – particularly among Jewish millennials in the US. In one such survey, only 38% of those under the age of 35 indicated that Israel’s existence was very important to them, compared to 70% of those 65 and older.

Many attribute their sense of alienation to what they perceive of as Israel’s indifference to the liberal values they hold dear, some to what they refer to as the ongoing occupation, and others to the obstinate refusal of the Jewish state to recognize the non-Orthodox streams, to which the vast majority of affiliated Jews abroad belong. But the real issue is much deeper than any of these factors. More than half of the younger generation questioned in one major survey expressed discomfort with the very idea of a Jewish state.

This phenomenon is something about which Navon cautioned us nearly half a century ago in his inaugural presidential address: “Entire sections of the Jewish people are falling away as a result of assimilation. A significant portion of those lost are idealistic youth who seek an exalted ideal… We must find a way to reveal to them the eternal values of Judaism and its great heritage; to awaken within them a sense of common historic destiny; to confront them with challenges that will win their hearts… We must approach them in ways that conform with their inner needs. We must sharpen our wits and find new outlets for these people. The old ways have lost their relevance.”

If this next generation were convinced that Israel is striving to become the sort of society Navon envisioned, things might be different. “May we build a society rooted in compassion, a society that has the power to end poverty, violence, political radicalism, and social polarization,” he intoned. “A moral, ethical society that will bring us pride, inspire worldwide admiration… and, above all else, wholeheartedly strive for peace.”

Navon is no longer here to guide us, but the government of Israel, recognizing the importance of perpetuating his legacy as “an outstanding symbol of unity, mutual responsibility, and social cohesion,” adopted a decision initiating the creation of the Yitzhak Navon Center for a Shared Society. This is now in the process of being built at Neot Kedumim.

A multifaceted experiential complex, it will provide a wide range of activities promoting familiarity with and mutual respect among Israel’s diverse populations. It hopes to achieve this by, inter alia, showcasing the culture of Sephardi and Mizrahi Jewry, the wellspring of Navon’s values – values which counsel us to follow the Rambam’s “golden path” of tolerance and moderation.

These values inspired the president’s lifelong devotion to fashioning Israel into an exemplary society in which all its citizens – Ashkenazim and Sephardim, religious and secular, new immigrants and veterans, right-wingers and leftists, Jews and Arabs, Christians and Druze – would feel at home.

May his memory be for a blessing and an inspiration for us all – incoming government ministers and Knesset members included – to help us overcome the strife that divides us and strive instead for reconciliation in the year ahead.

The writer is executive director of the Yitzhak Navon Center for a Shared Society. He previously served as deputy chair of the Jewish Agency executive and the World Zionist Organization, and as the conceptual architect and founding director of the Herzl Museum and Educational Center in Jerusalem. david@navon-center.org.il