The Mossad revealed decisively for the first time on Monday how its most famous spy was caught in 1965.

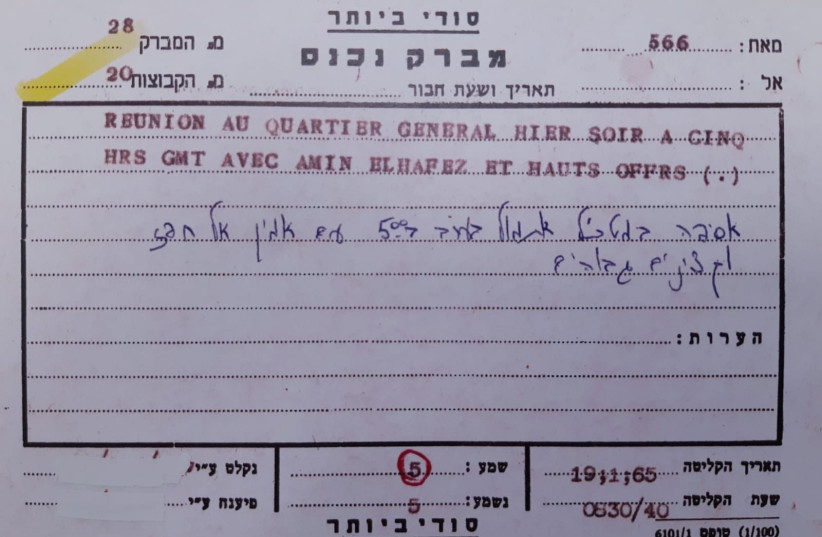

Mossad Director David Barnea disclosed on Monday the content of Eli Cohen’s last cable to the agency, on January 19, 1965, as well as that the cable was intercepted.

In the cable, Cohen reported to his clandestine supervisors that then-Syrian president Amin al-Hafiz had met with the Syrian military high command at 5 p.m. – this being just shortly before Cohen was captured.

For decades, there has been a debate about whether Cohen, who gave the Mossad significant information about top Syrian officials and armaments from the early 1960s-1965, was caught because his handlers pushed him too hard or he himself took too many risks.

Barnea said releasing the last cable was part of an effort to make it clear that no one was “to blame,” and that sometimes even the best of spies – and he rated Cohen a legend for his contributions to the organization – can be caught by persistent counterintelligence by an enemy.

Who was Eli Cohen?

He said Cohen “was not captured because he sent too many transmissions, because he did not act according to protocol or because headquarters pressured him into transmitting too frequently.”

“From now on, this is an intelligence fact,” said Barnea.

Cohen trained extensively and spent time in Argentina to build a deep cover story as a businessman with strong ties to Syria, and succeeded in befriending a variety of top Syrian officials.

During his time in Syria, he threw lavish parties for wealthy Syrians, especially security officials, connecting some of them with prostitutes and sometimes lending them money.

“Eli Cohen was among our best spies. He continues to impact us through his fighting spirit, courage, values and dedication” serving as a “source of inspiration” for the full spectrum of Mossad agents, said Barnea.

There is some debate among historians, but at least some credit the intelligence he provided as playing a crucial role in Israel’s success during the Six Day War.

However, some Syrians were already suspicious of him after an internal coup in 1963 and Syria also received new technological tools for detecting spy transmissions from the USSR.

Despite Barnea’s disclosure, some historians will continue to claim that Cohen wanted to stay in Israel in 1964 and was concerned about returning to Syria for another period of time undercover – the period in which he was caught.

Barnea made the revelation at a ceremony opening a new museum named for Cohen in Herzliya.

The spy chief also vowed to continue searching for Cohen’s remains.