Tel Aviv, only an hour by car and less by train and yet a world away from Jerusalem. The White City that never sleeps, its golden stretch of beaches hot, humid and inviting in summer, and on visits in years past, not the easiest place to find a kosher restaurant (fortunately for those looking, there’s no lack of them today).

But how did I not see, how did I not know, that it’s the most Jewish city in the world! A day tour opened my eyes, heart and mind to that very reality, and what better time to share this than on the anniversary of Tel Aviv’s founding on April 11, 1909.

The tour organized by my husband, Joe, and his friend Menachem had been advertised as providing a “unique perspective” on Tel Aviv, and our exceptional tour guide, Abraham Silver, imparted that in spades to the more than 40 participants who boarded the tour bus early on a Tuesday morning for the drive from Jerusalem.

Touring Tel Aviv: The most Jewish city in the world

Our starting point was a lookout in Jaffa, where the sunlit, azure sky merged with the green-streaked blue of the sparkling, calm Mediterranean spreading gloriously below us. Ahead and to the right, a crescent of glowing sand with the breathtaking panorama of Tel Aviv’s tall edifices reaching toward a cloudless firmament greeted us. Jaffa, which had for 4,000 years been a world center in this region and where every civilization had left its footprint, is today just a neighborhood of Tel Aviv.

We looked toward one of those tall towers which happened to be the spot where 60 Jewish Zionist families, who had come to Jaffa mainly from the Pale of Settlement in Eastern Europe, had stood on a desolate sand dune in 1909 and declared their dream to build a city.

We learned from our guide, Abraham, that the primary aspiration of that group gathered on the sand was not the building of a commercial metropolis but rather an ideological goal to establish the first Hebrew city, the most Jewish city in the world.

They were driven by the need for Jewish self-determination; by the pull of Zionism, to reconstitute the Jewish people in a modern setting; and by the push of antisemitism, which tends to turn people inward and prompts some to flee while seeking to make a better world.

In 1904 Chaim Nachman Bialik, ultimately recognized as Israel’s national poet, wrote a poem, In the City of Slaughter, which Israeli schoolchildren still learn, referencing the Kishinev Pogrom and espousing the evils of the Diaspora. A notional thread may stretch from there to the families assembled on the sand of Palestine five years later who resolved to build Tel Aviv.

They may have been thinking of New York to where most who left Europe had fled (less than one percent went to pre-state Palestine), but their dream was to build their version of New York, not the New York of a Diaspora where Jews would be killed if not today, then tomorrow.

Bialik’s famous Israeli children’s song Nad Ned (see-saw) also alludes to Jews (and not their rabbis or anyone else) determining their own fate, and to an equilibrium between secular and religious Jewish ideals.

Through an appreciation of these dreamers and builders, and how Tel Aviv was created to challenge everyone, our guide opened windows to an understanding of Israel and its people.

The name chosen in 1910 for the new city, Tel Aviv, translated the title in German of Theodor Herzl’s book Altneuland (“old new land”), whereby the ancient (tel: an archaeological mound of past civilizations) pairs with rebirth and renewal (Aviv: the season of spring). The manifesto of those dreamers and doers was to build a city where everyone would be Jewish, planned according to rules of hygiene and aesthetics, where everything would be done to reflect and complement life as a Jew.

Memorable stories of Tel Aviv's history

MANY OF those who came to Palestine on the second aliyah between 1904 and 1914 from Eastern Europe were youngsters, 17-18 years old, full of youthful idealism. They had left their parents in Europe, often without their consent or blessing, and faced the hardships alone.

Together, they followed the initiative of 1909 to build the Jewish city. They were instrumental in setting up the organizations and building blocks of a new society based on three premises: land of Israel; defense of Israel; and Jewish culture (which paid heed to biblical connections but not to the Diaspora which they did not want to replicate or reflect).

Further, they didn’t want to speak Yiddish but developed and learned non-biblical Hebrew; they rejected European food and preferred the Sephardi menu of the surrounding Middle East.

In essence, Israel was created by typically dogmatic teenagers who applied their summer camp and Zionist movement experiences to build a society, manifested in customs such as singing around the campfire and informality in meetings, including even among senior army leaders, which has carried through to today.

We heard all this from our passionate guide while walking around Neveh Tzedek, a neighborhood of Tel Aviv. We made stops along the way, such as the original yeshiva, Torah v’Avodah ,where Torah studies are combined with training in different professions. In 1924, this yeshiva became the basis of the Mercaz Harav Yeshiva in Jerusalem of Rav Kook.

We also visited the house where Shmuel Yosef Agnon (Shai Agnon), winner of the 1966 Nobel Prize in Literature, had lived. While living there, his first published story about agunot (Jewish women who are “chained” to their marriage) led to his choice of “Agnon” to replace his very European surname, Czaczkes.

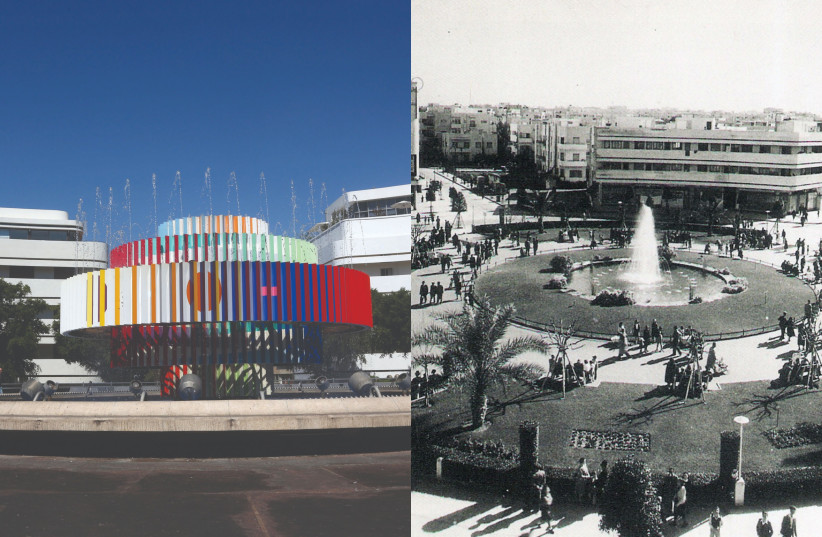

OUR WALK then led us to 10 Rothschild Boulevard, the magnificent modernist Bauhaus-lined, busy thoroughfare, where a small white wooden kiosk marked the spot where those families in 1909 had declared their dream. The kiosk has been there since there was barely another building in the vicinity and is now a symbol of the creation of a nation.

The flattened sand dunes in 1920 housed 2,800 people, which 10 years later became 30,000-40,000, and 150,000 by 1940. Tel Aviv today is a city of about 450,000 people including around 30,000 Arabs, within the greater Tel Aviv area of Gush Dan (where the biblical tribe of Dan settled).

On Herzl Street, visible from the small kiosk, is the site of the country’s first Hebrew high school, Gymnasia Herzliya. Among our guide’s countless gem-like anecdotes was the story of Israel’s second prime minister Moshe Sharett, who co-wrote Israel’s Declaration of Independence. On his grave, however, Sharett insisted on the inscription relating to his more modest claim to fame: his place among the first graduating class of Gymnasia Herzliya!

Another memorable story was that of Ahad Ha’am, a noted pre-state Zionist thinker, who when he heard a street was to be named after him, famously exclaimed: “All my life people yelled at me, and now they’ll spit on me!”

Our guide’s observations and explanations drew together many jigsaw pieces to form a picture many of us had not considered. Tel Aviv is Jewish like Paris is French. It presents a Jewish understanding of the world and provides for the living of a full Jewish life culturally, if not necessarily religiously, although the city has some 550 active synagogues.

Today, there are also secular yeshivot, and on Friday afternoons between 14:00 and 16:00, kabbalat Shabbat songs are played in bars. The city’s streets are not designed as a grid with crosses but as curves like branches of a menorah or in the shape of a Magen David. The main roads run north-south and not towards the beach, hence avoiding facing the coast which looks in the direction of abandoned Europe.

We heard too from Abraham – who is also an architect – about the city’s buildings: modernist, internationalist, and of course the Bauhaus style, featuring simple geometric shapes such as the rectangles and circles of Mondrian art of the 1920s and ‘30s. These asymmetric buildings are characterized by simple lines and functionality, with many featuring those curved balconies which first grab the eye. They don’t give away whether their inhabitants are rich or poor; they can equally be home to both.

THROUGHOUT THE tour, Abraham Silver’s passion for the story and city of Tel Aviv was so ardent and vivid we could almost touch it.

He left us to ponder some final thoughts. Tel Aviv has managed until now to be perpetually Jewish – will that continue to be its future? No doubt there are and will be challenges, but Abraham believes Rav Kook would say: “They (the Jews) will find their way.” ■

The writer was a lawyer in Melbourne, Australia, before she and husband Joe made aliyah in 2015 to join their children in Jerusalem. She writes and reads for pleasure and emotional sustenance.