From 1940 to late 1944, the residents of the town of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and the surrounding farms and villages in south-central France provided refuge to an estimated 5,000 people, mainly Jews, who were fleeing the Vichy authorities and the Germans.

That little known bit of history from the Holocaust isn’t known to many, but to some residents of Meitar, the middle class northern Negev town of 10,000, 20 km. north of Beersheba, it’s a big deal.

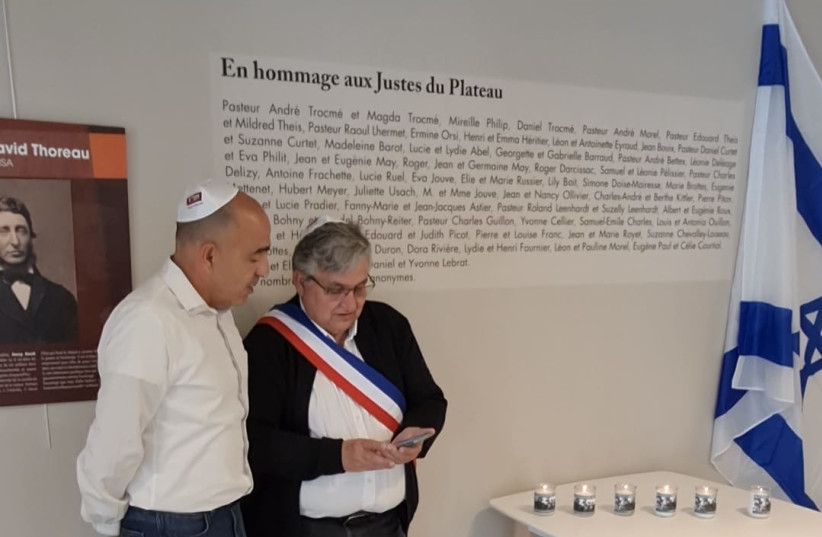

That’s because Meitar and Le Chambon-sur-Lignon are sister cities and several Meitar residents have been annually visiting the French village for Yom Hazikron for years, forming a close bond with the present and past mayors.

The relationship wasn't publicized

Over the years the “sister city” relationship was not even mentioned in annual Meitar Holocaust Day ceremonies. But a few years ago Shimon Peretz, a member of the Meitar Municipal Council, was visiting France and, curious about Le Chambon, decided on his own to visit the town.

“I didn’t tell anyone I was going or make any arrangements,” relates Peretz, a retired IDF officer. “I stayed in a local hotel, walked around the town and then just showed up at the municipality. The mayor at the time Éliane Wauquiez invited me into her office and she told me her story.”

Wauquiez, originally from Belgium, hadn’t known about the town’s background until after she decided to buy a summer home in the mountain resort region 20 years ago. “At the time people spoke very little about the story of rescuing and protecting the Jews during the war,” she relates in a phone interview, explaining that once she learned about the region’s amazing past she envisioned setting up a museum dedicated to preserving the history of the plateau. “It was very difficult to get the idea off the ground. This was especially true because of the residents’ profoundly held Calvinist belief in humility. They didn’t want to boast. I tried to convince them, that if you don’t tell the story it will disappear.”

SHE DECIDED to become involved politically in the town to promote the idea, and was elected mayor. Wauquiez, herself a Catholic, met in Paris with members of The Society of Protestant History in France, then, with their tacit blessing managed to find donors for the museum. The small glass enclosed museum, Lieu de Memoire, opened in 2013, and has been awarded the European Heritage Label of the European Commission.

It was following Shimon Peretz’s initial meeting with Éliane Wauquiez that he vowed to return to the town every year. Aside from the pandemic years, he’s returned to France with small groups of Meitar residents to visit Le Chambon every Holocaust Day. “I do this alone at my own expense. We need to say thank you,” he states.

Naama Elhaddad, a member of the Meitar Municipal Council, and her husband Netanel went to Le Chambon in 2019. “The renewal of the connection with the municipality and the people was very moving, not just something on paper,” she says. “Many of the local residents came to the ceremony for Yom Hashoah, even the mayor who signed the original agreement, though he was very ill.”

The sister city agreement

The sister city agreement between Le Chambon and Meitar was signed in 2006. It followed an initiative by Meitar resident Huguette Elhadad and her partner Nissim Zvili who was Israel’s ambassador to France from 2002 to 2005.

“They came to me with the idea; Le Chambon is close to the French city of Lyon, which is the sister city of Beersheba, that’s like our distance from Beersheba,” recalls Solomon Cohen, who was head of the Meitar Municipal Council at the time, and one of the founders of the community. “When I heard the story, I went to Yad Vashem to see the memorial site and plaque erected in the town’s honor and decided to present the idea of an agreement to the Council.” Following the ceremonial signing, Cohen brought a group of youngsters to Le Chambon, hosted Le Chambon’s mayor at the time, Frances Valla, in Meitar, and persuaded the JNF to plant a eucalyptus grove in Meitar to honor the pact.

Cohen concedes that few Meitar residents today know about the connection with Le Chambon. “I speak French and we kept up contacts for awhile. But once a new mayor took over in 2008 the issue cooled,” Cohen explains.

The connection between Le Chambon and helping those in need is not restricted only to the Holocaust though. In March 2022, less than a month after Russia invaded Ukraine, setting off Europe’s largest refugee crisis since World War II, a Protestant pastor in a remote village in south-central France drove to Ukraine and brought back a group of refugees. Today there are some 200 Ukrainian refugees sheltering there. In the past decade villages in the region have taken in migrants from many war zones, including Syria, Kosovo and Rwanda.

The ethos and practice of the rescue and sheltering of refugees has a long history in the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon area in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of France.

The central town is Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. The risks the villagers took during the war were extreme; the penalty for sheltering Jews was death, but astonishingly, no one betrayed them. No other communal effort on this scale ever occurred for this long anywhere else in occupied Europe.

THIS EXTRAORDINARY BRAVERY became public in 1990 when the village and surrounding area were recognized as “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem. Since then 90 individuals from Le Chambon and its environs were designated as “Righteous”. Two films – a documentary and a fictionalized drama – have been made about Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, as well as a dozen books and studies.

The remote plateau is known as La Montagne Protestante (the Protestant Mountain) because it was settled long ago by French Huguenots fleeing religious persecution by the Catholic authorities. Its isolated location made it an ideal haven and it sheltered fellow Huguenots (Calvinist Protestants) during the religious wars of the 16th-18th centuries.

During the war the area was part of the Vichy “Unoccupied Zone”, allied with Germany, until 1942 when the German took over completely. Most of the Protestants in the area refused to cooperate with the Vichy government.

Under the leadership of Pastor André Trocmé of the Reformed Church of France, his wife Magda, and his assistant, Pastor Edouard Theis, the residents of the villages offered shelter in private homes, hotels, farms and in schools. They regarded the Jews as the chosen people, the people of the book. Villagers also opposed the government’s anti-Jewish policies, seeing the Jews as a fellow persecuted religious minority. They forged identification and ration cards for the refugees, and in some cases guided them across the border to neutral Switzerland.

The refugees were mostly foreign-born Jews, a majority were children. They were dispersed among the small isolated villages and farms in the mountainous region surrounding Le Chambon. Whenever the villagers learned of impending visits by the Vichy police or German Security Police raids, the refugees were sent into the countryside, or hidden in underground rooms. Some were escorted to the Swiss border. The region also sheltered members of the French resistance, including French Jews who learned how to use weapons from veterans of the Spanish civil war who were also hiding out in the area.

IN A FATAL INCIDENT, reminiscent of the story of Janusz Korczak, familiar to Israelis, Daniel Trocmé, was principal of two boarding schools in Le Chambon housing mainly Jewish refugees. In June 1943 Gestapo troops raided one of the schools for older students, arresting 18 students, including six Jews. Trocmé was not on the grounds at the time, but although he was urged to flee, he chose to return and joined his students as they were sent from camp to camp. Trocmé eventually died in the Maidanek concentration camp near Lublin.

In his award-winning documentary Weapons of the Spirit, released in 1989, film-maker Pierre Sauvage tells the story of the area of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, how this Christian mountain community in Nazi-occupied France took in and saved thousands of Jews, including Sauvage and his parents. He calls it a “conspiracy of goodness”.

In the film Sauvage interviews the then elderly Henri and Emma Héritier, the peasant couple who had sheltered the village forger and other Jews, and also took care of the film-maker’s family. “We never asked for explanations, nobody asked anything when people came to ask for help,” says Henri in the film. When the film-maker asks why they would shelter Jews at great risk to their own lives, Emma simply smiles and shrugs: “We were used to it.”

The newly remastered wide-screen 2023 edition of Weapons of the Spirit (Neshek Haruach) will be released in the coming months.