Diversity has been a rallying call for corporations in the West for years, creating debate about the roles of merit and equality in the workspace. Proponents of increased diversity argue that policies that benefit minorities and underprivileged citizens give them opportunities that they would otherwise not have, and right historical wrongs against these groups.

Critics have said that such endeavors create new privileges and inequalities between different demographic groups, and sacrifice the rewarding and promotion of diligence and talent in favor of workplace metrics based on immutable characteristics.

While these furious debates will likely continue for years to come, leading Israeli law firm Herzog, Fox & Neeman has demonstrated a different approach to diversity that it claims has expanded its talent pool for employees; hidden gems that might otherwise not have enhanced the company with their skills because they lay behind cultural and religious barriers.

Expanding the talent pool

Originally from the United Kingdom, Herzog’s managing partner Gil White joined the firm in 2000 when the firm had 40 lawyers.

“Nobody ever dreamed we’d be a hundred lawyers, let alone that we’d be as we are today with 450 lawyers,” recalled White.

The firm had grown over the last 20 years, with the expansion of the Israeli economy and a flood of foreign investment into the Jewish State.

“This firm sat on the axis for foreign investors coming into Israel,” said White. Herzog began to work not only with “the Facebooks, Microsofts, and Googles, and all international investment banks doing business in Israel, but also a huge number of Israeli investors who are doing business outside of Israel.”

As the law giant sought to maintain its competitive edge, Herzog began to expand the number of high quality lawyers and employees that it could recruit beyond the oft-tapped resources of schools like Bar Ilan University or Tel Aviv University. While these talent pools hadn’t dried up, an expanded total number of candidates could also mean a greater total number of superior options.

“We came to the realization some years ago that there were pools of talent in Israeli society that we were not appealing to. And if we wanted to keep growing and to attract the best talent, we needed to appeal to all communities of Israeli society,” said White. “This is a business need. The fact that we can get the brightest minds from the Arab community, from the haredi community, is a real benefit.”

White said that if Herzog wanted to grow “from 450 lawyers to 550 lawyers to 650 lawyers, we need to attract the best talent from every section of Israeli society.”

According to the law firm, over half of their employees are women, with a high number of new immigrants, people who studied abroad and significant representation from the LGBTQ community, but White emphasized that the firm did not relax requirements to achieve these figures. These employees had gained their positions through hard work and skill. Far from giving up on merit, White explained what Herzog did change, was its understanding of how to identify and attract potential attorneys and interns from different communities.

Identifying talent beyond cultural barriers

Mordechai Fogel joined Herzog in 2021 and works in the firm’s tax department, and also serves as a lecturer in tax law at Ono Academic College. Previously, he worked for eight years as a senior department manager for the Israel Tax Authority. An ultra-orthodox religious Jew, Fogel learned at a kollel, an institution for the study of Jewish religious scripture.

While Fogel saw his knowledge of Torah and Talmud as aiding him in his study of law, he noticed that some of his haredi students were removing their yeshiva study from their curriculum vitae. Fogel would ask students about massive time gaps in their resumes, warning them that potential employers would want to know about them.

“They were embarrassed to present it [Torah studies],” said Fogel. “I can look at their curriculum vitae and understand in a second based on the name of the yeshiva what they learned and the quality of the institution.”

Herzog associate Dana Qaq, whose Jerusalem Muslim family has roots in the holy city going back 1400 years, overcame challenges with languages during her impressive educational journey.

“We went to a lot of international diplomatic schools, so we were always exposed to English and everything,” Qaq recalled. “Because I grew up at home speaking Arabic and English, the major decision was, do I stay in this country, spend my time trying to learn Hebrew, or do I go abroad, kind of take the longer way, get my education and then come back, learn Hebrew and do everything all over again.”

Qaq took the long route, earning her LLB at Cardiff University – as well as accolades such as being a two-time recipient of the law school’s International merit scholarship for outstanding academic performance. She earned, with distinction, her Master’s in corporate law at Cambridge University, the first from the country in the program, and was a general editor of the Cambridge International Law Journal.

“When I came back I kind of was in shock because I didn’t know Hebrew,” said Qaq.

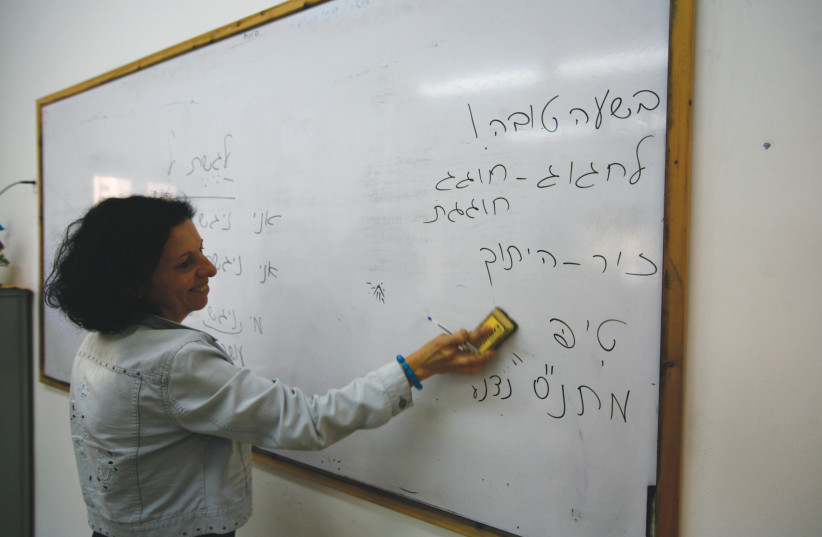

Qaq spent half her time studying in a Hebrew Ulpan, and the other half doing her Israeli law prerequisite exams. She passed, and interned at a Jerusalem law firm where she pushed herself to work in Hebrew, enabling her to later take and pass the Israeli Bar Association exam. Then she applied to Herzog.

While Qaq’s Hebrew has vastly improved over the years, an interviewer speaking to a highly educated and motivated individual like her might gloss over her immense potential because of her lack of language skills.

According to Qaq, a firm needs to be able to ”recognize and appreciate the differences in background and to be able to understand where the individual has come from and the obstacles that they’ve gone through in order to get to a certain point, because that naturally plays into the professional that that person is right now.”

White said that many Israeli-Arab students struggled in their first year of studies, in large part due to language skills. A recruiter might look at lower grades in the first year and fail to take this additional challenge into account, rather than focus more on the latter years of study where their language faculties had improved.

“To understand a CV of people from different societies in Israel is a challenge. If I just judged her [Qaq] on her Hebrew, I wouldn’t get anywhere. Motti [Fogel] studied in an educational establishment which you need to understand is where the haredi community goes and studies,” said White. “We spend a lot of time speaking to the interviewers before the interview so they understand how to read the CVs, what questions to ask.”

Thanks to this diversity consideration, White said that Herzog had recently enjoyed one of their most successful recruitment drives – which also happened to recruit many quality interns from the Ethiopian-Israeli, Arab, and haredi communities. Qaq said that she was part of an institution that had the tools, not only to recognize talent, but to also develop it.

Awareness of opportunity

Dr. Ehab Farah is senior partner in Herzog’s corporate tax team and a tax professor at the Faculty of Law at Haifa University, representing international clients doing business in Israel for over seven years. A member of the Arab community in Israel and a Greek Orthodox Christian, Farah jumped back and forth between Israel and the United States in his youth, education, and legal practice, before settling down in Israel because of his strong connection to his hometown, society, community, and friends.

Farah emphasized that Herzog had gone through a significant learning process to integrate all the elements of Israeli society into the firm.

Recruitment wasn’t just about being able to interpret the value of a resume, but also about engendering an understanding of the opportunities available to them and encouraging them to apply. Farah said that Herzog had to ask himself why Arab community members weren’t sending their CVs.

“If you look back to when I studied in the 1990s, there weren’t Arab students that were thinking about applying to big law firms. It wasn’t on the table for them,” said Farah. For the firms, “It wasn’t an item on the agenda as opposed to what’s going on now.”

Then Herzog had an open day for Arab students. The managing partner came, food was set up, and the reception team was ready – but no one came. They thought it was enough to announce the event, and people would come.

“You can’t just wake up on Sunday and introduce a diversity program and imagine that a week later the corridors will be full of people from diverse backgrounds,” said White. “We produce recruitment brochures; we produce them in English, we produce them in Hebrew. For years now, we have produced them in Arabic. But it’s not just sending them a translator to translate them into Arabic. There are different nuances in the language. So we have people spend a lot of time sitting and reviewing the materials because you want people to read it and to relate.”

Arab students may know Hebrew, but something as small as having brochures in Arabic helps establish a firm as being a realistic option for them.

Fogel said that when he was studying law just over a decade ago, “I didn’t think that a firm like Herzog would even look in my direction. There wasn’t even a single person in our class that applied to Herzog or a firm like it for an internship.”

The landscape had changed, said Fogel. He was seeing new haredi interns, and more applying. Things like seeing a lecturer such as Fogel changed their beliefs about what was available to them. He related a story of a major case before the High Court of Justice that didn’t have anything to do with haredi society, in which both sides had haredi attorneys.

“This is a picture of success, which shows that haredi society is headed to a better place.”

Integration of diversity

To make working with Herzog seem attainable, Farah said that the firm had made diversity part of its agenda. White described it as having diversity in the DNA of the operations. He explained that it wasn’t enough to invite people into the firm, but include them into the office’s social and work fabric.

“If you have an associate in a particular department who fasts every Ramadan, our diversity program doesn’t mean anything if the people who she works with day-to-day in that department don’t understand what the implications of having somebody who fast in Ramadan are,” said White. “Our diversity program doesn’t work if somebody in the litigation department doesn’t understand what Tisha Be’av is.”

Herzog celebrates Jewish, Christian, and Muslim holidays, which makes all employees feel involved, not only with the firm, but increases workplace cohesion.

Qaq said that the HR and marketing departments were constantly reaching out to her to understand more about Muslim holidays like Eid al-Adha. She also was happy that her colleagues were approaching her, asking questions to learn more. In celebrating these holidays, colleagues could learn more about one another on a personal level, which helped the department and the firm as a whole.

“I think it’s a way for people to see that regardless of the differences, as many differences as there are, there are also a lot of similarities,” said Qaq.

White said that they were not naive to the realities of the Middle East, and tensions between groups that had to be left outside the office. Creating an atmosphere of mutual respect was important to continued operations, and making all employees feel welcome secured this internal harmony.

Benefits of diversity

White explained that integrating diversity into the firm had benefits beyond expanding the pool of qualified applicants.

“The legal world has changed, particularly over recent years, where clients look for their lawyers to be much more of an integral part of what they’re doing,” White said. He cited a recent survey of the top 250 US companies, and on what basis they chose outside legal counsel.

“The number one [basis] was not legal fees, was not professionalism – the number one factor was somebody I’d want to go and have a drink with. So this ability and requirement today for lawyers to be able to interact with their clients on a person-to-person basis is of supreme importance. Our clients come from the entire spectrum of Israeli society, but also internationally. The fact that we’re able to build a law firm which, to some extent, mirrors that makes our clients feel much more comfortable.”

The Abraham Accords had created new opportunities within the legal field and in general, for Arabic speakers in Israel to use their language skills, said Farah.

“It’s obvious there is talent in this small country and there is a lot to do with Arab countries,” he said. There were always connections, but the Abraham Accords, “makes it easier to facilitate it, makes it easier to have open and public relations. We have more conferences, we have more client meetings, we have more agreements. It’s a lot easier to sit down and do business.”

While many business proceedings were conducted in English, Farah said that Arabic language skills could make clients more comfortable and make certain transactions easier. He was happy to provide these personalized services.

Making clients comfortable was more than just about language, but understanding cultural nuances. Fogel shared that he had been directly contacted by ultra-orthodox clientele who wanted to work with him, because they felt it easier to convey what they wanted and why they wanted it to him.

White noted that many Western businesses held diversity as an important value. They want to “feel that the institutions that they’re working with reflect their view of society.” White felt that Herzog could demonstrate that in a truly genuine matter.

Merit and diversity

Diversity is a two-way street, Qaq noted. While the firm had to make itself available, it was up to the individuals to not allow themselves to be victims of circumstance, but to understand that they can reach the heights of a prestigious law firm by working hard.

Both Qaq and her brother work at Herzog. Their parents didn’t have the same opportunities that they did, and their father focused on making sure they had an international education to give them as many opportunities as possible. Both Qaq siblings went to the UK to study – while her brother had a tendency to copy her since he was little, she came to see it as a healthy competition to improve, such as with grades.

They were also in competition with the expectations of others. Qaq said she had been told, “you’re never going to learn Hebrew, you’re never going to become a lawyer here, you’re not going to be able to do it.”

Qaq hoped that she could serve as a role model as much as possible for women, and especially those from the Israeli-Arab community. She said that she had many girls reach out to her asking how they could do what she was doing. She could speak to her experience about how hard she had to work, but hoped that she could lay the path for others to make their own path also.

“Where I can I help, even if it’s as small as speaking about Eid al-Adha, or speaking to an intern in Arabic and encouraging them to do it because it’s attainable – you just need to have a person who’s willing to understand you and is willing to push you.” ■