One of the sad facts of life is that, for the most part, we don’t recognize the icons in our midst until they are dead.

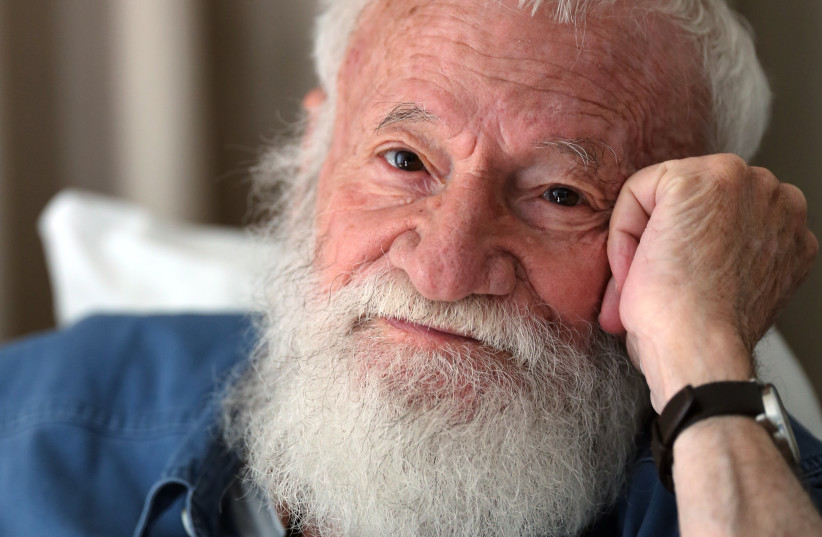

Such was the case with Yoram Taharlev, prolific lyricist, poet, author, essayist and stand-up comedian, who died on January 6, just over two weeks before his 84th birthday.

There is a certain symbolism in the fact that he was born in January, died in January, was born in Kibbutz Yagur on the northeastern slopes of Mount Carmel, and was buried there last Friday, even though he had not lived there for the major part of his life.

But he had remained in touch, and frequently returned to share memories with childhood friends and others whom he knew from the years that he had lived there in the early years of his marriage to his first wife, author and poet Nurit Zarhi, whom he married in 1963 and divorced in 1975.

He subsequently remarried in 1978. His second wife, Linda, an immigrant from the United States, died in 2011.

In 2014, he married Batia Keinan, a former spokeswoman for president Ezer Weizman, who took it upon herself to promote Taharlev, who, despite his popularity, she believed was underappreciated.

Taharlev had two daughters, Roni and Arela, with his first wife, and a son, Daniel, and daughter, Michal, with his second wife. He also had nine grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Creativity apparently runs in the Taharlev DNA. Both his children and grandchildren are talented in various spheres of the arts, mostly music, though Roni Taharlev is a well-known painter and sculptress.

Taharlev’s Lithuanian-born father, Haim Taharlev (formerly Tarlovsky), was also a writer, but nowhere near as well-known as his son. His mother, Yaffa Yitzikovitz, was likewise from Lithuania, but his parents did not know each other in the old country. They met at Kibbutz Yagur, which this year celebrates its centenary. It will be a celebration that Yoram Taharlev would have loved to attend – but it was not to be.

He would also have loved to attend the inauguration this coming Wednesday of the new headquarters of the Kibbutz Movement, which, after 70 years in Tel Aviv’s Leonardo da Vinci Street, has found a new home. The mezuzah on the new premises will include lines that he penned. When asked permission for this, he was emotionally moved, and agreed wholeheartedly.

It was not generally known that Taharlev was battling cancer. He kept on making stage appearances until a week before his death, and was making plans for future gigs.

GROWING UP on the kibbutz, the young Yoram demonstrated an early talent for writing poetry. He was only seven and a half when he produced his first masterpiece.

His parents were so proud of him that they went to Haifa, purchased a fine notebook for him, and told him that every time he wrote a poem, he should copy it into the notebook. They arranged a special corner in the bottom drawer of their cupboard for the notebook, so that it should be easily accessible to the young boy.

In those days, kibbutz children did not live with their parents, but were raised in a children’s house, in accordance with the socialist ideal. His parents told him that he was always free to come to their hut and write in the notebook.

One Saturday, near the end of June 1946, the kibbutz was invaded by a convoy of British soldiers looking for hidden weapons. In the children’s house, the youngsters were rounded up by their caregivers and taken to the kitchen, where supplies of food and drink had been stored in case of emergency.

The kibbutzniks tried to hold the soldiers at bay, but were no match against tanks and tear gas. Many were taken prisoner, loaded onto trucks and transported to a prison camp in Rafah. It was four months before the children of Yagur were reunited with their parents.

The soldiers ransacked the kibbutz in their search for arms. There was no respect for property. Floors were dug up, flimsy furniture was broken, and contents of cupboards and drawers scattered all over.

The search went on for a week – including in the children’s house, after which the British displayed a huge cache of weapons amounting to an arsenal, to prove their claim that the Jews were amassing illegal arms.

As soon as the soldiers left the kibbutz, Taharlev ran to his parents’ hut, which had been almost completely destroyed, with rubble everywhere. He searched in vain for his notebook, but it was nowhere to be found. Try as he might, he could not reconstruct his poems.

This had a traumatic effect on him which lasted till the end of his days.

What had befallen Yagur might have been buried in the dust of time, had it not been included in so many of Taharlev’s writings.

In fact, through his poems and song lyrics, he recorded much of modern Israel’s history, both in war and peace, and in doing so became an informal teacher, because many of these songs became so popular that large numbers of people actually learned from them and acquired knowledge about events, places and personalities of which they had previously been ignorant.

Taharlev stayed on the kibbutz till he was 26, working as a beekeeper, fruit picker and gardener.

After he moved to Tel Aviv, his career as a lyricist gained momentum.

It was known that he was prolific and that he worked with many top recording artists, but even disc jockeys admitted after his death that they had not realized that he had written the lyrics for close to a thousand songs, many of which were among all-time favorites, and were frequently played on radio and television, and sung at community singing gatherings around the country and at commemorative ceremonies.

Moreover, in addition to being a talented lyricist, Taharlev had an uncanny ear for music. Matti Caspi, speaking on KAN Reshet Bet from Italy, where he now lives, said that he had composed a melody which he hummed to Taharlev over the phone and had asked whether he could come up with lyrics to fit it. Within a couple of hours, Taharlev had faxed him lyrics which completely blended with the melody.

Taharlev loved the Hebrew language, which he explored and exploited through every possible expression and nuance. Though secular, he also loved Jewish sources, which he delved into with a passion, and interpreted in a way that would make them interesting for secularists like himself. He had a great respect for Jewish wisdom.

In addition to writing for recording stars, he also wrote more than 130 songs for army entertainment troupes.

Taharlev had a wonderful sense of humor and a gift for stand-up comedy, in which he also recounted the story of Israel’s development, or referred to biblical sources, but in a way that made his audiences rock with laughter.

Many of the people who worked with him, such as Shalom Hanoch, Yardena Arazi and Dorit Reuveni, could not understand why he had never been awarded the Israel Prize.

In an interview with Taharlev on Reshet Bet in 2019, Geula Even-Sa’ar asked him if it bothered him that he had not received the Israel Prize, to which he replied that if he gets it, fine, and if he doesn’t get it, it’s also fine. What’s more important, he said, is the affection he receives from audiences. He also commented that, with or without the Israel Prize, he was sufficiently well known.

Taharlev also had a day job in the offices of the Defense Ministry, which explains why Defense Minister Benny Gantz was among the speakers at his funeral, which was held at Habima Theater before it concluded at Kibbutz Yagur.

When Even-Sa’ar asked Taharlev why he needed to work in an office, he replied that few people can live on creativity alone, and noted that best-selling author Amos Oz was a university lecturer, and composer Moshe Wilensky had a day job at Israel Radio for years. Both were Israel Prize laureates, as was composer Sasha Argov, who worked in a bank and later operated a bookshop.

It’s sad that Taharlev did not know just how beloved he was. News of his death was published on both the front and inside pages of several newspapers. He was eulogized by President Isaac Herzog and Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, as well as by Culture and Sport Minister Chili Tropper, who spoke of his talent, his love of people and nature, his Zionism, his Judaism and his pride in, and admiration for, both, and the rich legacy that he had left for generations to come .

Others, in speaking about him or in social media posts, noted that he reflected the best in Israel’s aspirations as a nation.

Songs for which he had written the lyrics were played on radio and television programs on the day of his death and the days that followed – and not just on musical programs.

Homage was paid to him on both news and feature programs, and word was broadcast that this will continue for some time to come.

In a sense, that was a far greater tribute than being awarded the Israel Prize, though Gantz and Tropper each pledged to work toward it being awarded to him posthumously.